“In 1601 William Shakespeare wrote, ‘We know what we are, but know not what we may be.’ To learn what we may be, we say to you, please turn these pages.” (xviii)

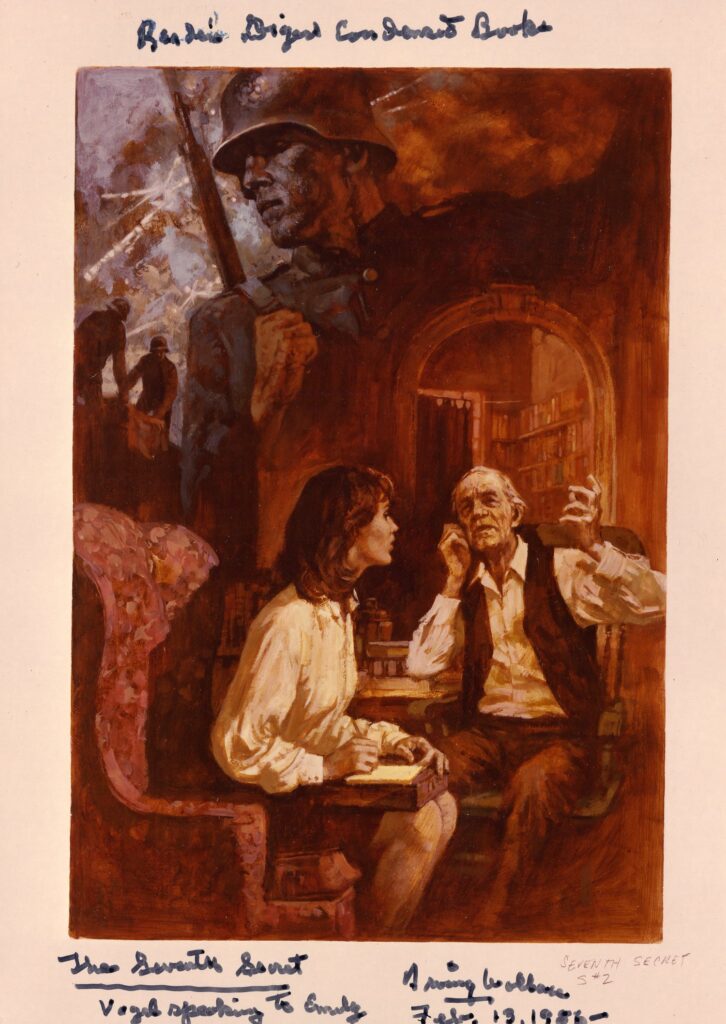

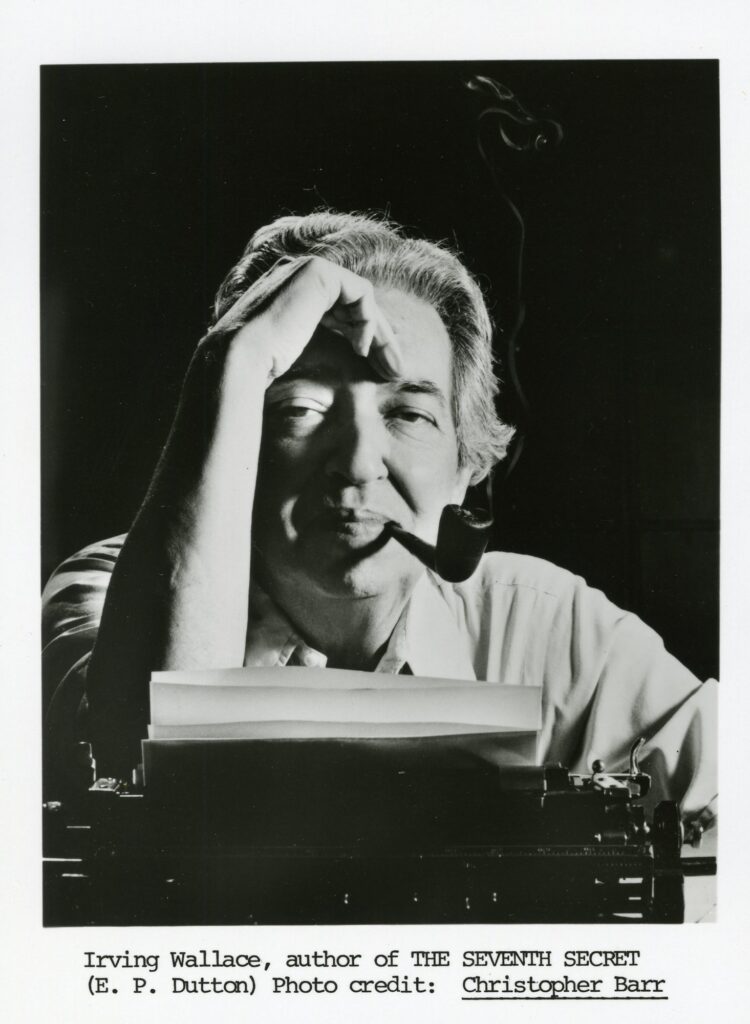

From the wits of scientists, politicians, authors, and psychics comes The Book of Predictions, originally published in 1981, by Irving Wallace and co-authored by David Wallechinsky and Amy Wallace. As a forecast for the future, Wallace gathered the postulations and presumptions from specialists for 1985 and beyond. Browsing through the collection, a variety of subjects are covered including outer space, language, military, home and family, health, income, transportation, and history of predictions.

To highlight a few predictions: 1990 The first human will be successfully resuscitated after being frozen. 2000 Ultra-high speed, magnetic-levitation, linear-motor trains will become standard means of intercity transportation. 2010 Intercontinental travel will be done with rockets which fly outside the earth’s atmosphere. 2020 We will be able to prevent earthquakes by injecting water into wells along faults in the earth. 2030 The law of gravity will be repealed, and facelifts will no longer be necessary.

The predictions on space migration, developed by Nigel Calder, New Scientist magazine editor from 1956-1966, had an meteoric pace. For the trajectory of migration to the stars, Nigel predicted by 2020, machines would prepare space for human habitation. And by 2030, the first human colony would be established.

If you were to make a prediction for fifty years in the future, what would you envision for 2075?

Stay tuned, Chelsea Fox