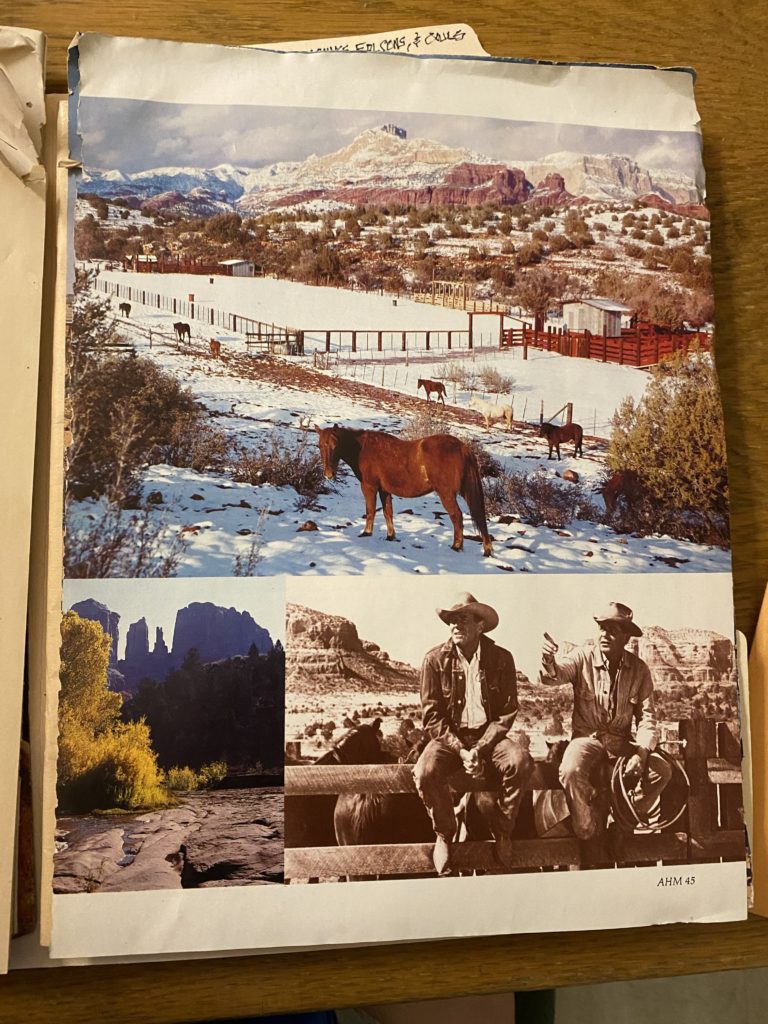

Around fire season every year, I often reflect on our California hillsides. And while over recent years the dialogue has advanced from managing foothill wildfires to climate change and unprecedented forest fires, I still get into the weeds, mulling over questions about ecological restoration, conservation, agricultural practice, and bioengineering. Today, it was a bit of synchrony coming across “The Land of the People” in A Journey to Tovangar by Mark Frank Acuna in the Drake collection.

Similar to Naomi Klein’s distinction, I’ve always separated two approaches to ecological/environmental restoration: bioengineering or letting nature heal itself. I have often erred to the side of letting nature heal itself and for human mitigation, especially around the development and practice of new technologies, to be minimal if at all. The thinking was always that nature could best heal itself over man’s hubris. This train of thought would often extend to my viewpoints that perhaps devalued the celebration of agricultural practices. I had over years lamented the idea and colonial logic that an agricultural turn signaled the progress of mankind, cleaving the civilized from the barbarian.

On reading Acuna’s paper, he offered a novel provocation to this line of thinking for me. He submitted that the California hillsides we see today would be completely unrecognizable to the Tongva and indigenous populations of the Southern California pre-twentieth century. He argues that it was not because they were more lush or wild, but that the hillsides were in fact profuse with oak trees that were cultivated and managed by indigenous tribes.

Acuna writes, “When the Spanish came through in their first years of conquering encounter, they all noted the park like vistas and the open clear Oak forests. They had not entered the wilderness but a well managed landscape. Even as late as 1844, John Fremont noted that ‘…the…groves of oaks give the appearance of orchards in an old cultivated country” (Fremont in Pavlik, 105). Somewhat similar to groves seen today, the forests were landscaped to be absent of grasses or competing tree species. They were open and “light-filled,” stretching from the mountains all the way to the sea, we individuals could walk “never having to leave the comforting shade of the Oaks” (Acuna, 17).

It is unknown exactly when this happened, but eventually indigenous tribes in the region became more and more reliant on acorns, “Kwar.” Horticulture techniques were developed between neighboring tribes and the Tongva became tenders and keepers of the Oaks (Weht). Three techniques were used in managing the vast oak forests: first, was a “careful and precise” fire to clear underbrush (which would reduce the pests and diseases often attributed to affecting forests and spur grass and forb seed production); second, they used long flexible poles to harvest acorns and prune (encouraging lateral growth to increase the size of the canopy); and lastly, methodically weeding the forests.

Acuna writes, “Two hundred years later, these managed chaparral and hillsides would be wilder and more deadly than they had been to the Tongva” (Acuna, 18). He admonishes the California Legislature and State and Federal Forestry agencies in the 1920’s who halted woodland burning for not even trying to understand or learn from indigenous practices. Returning it to the what they’d consider an “original” landscape was informed by a legacy of the missionary policy to “civilize” the Tongva by “denaturalizing them” (Acuna, 19).

Balance, care, and respect for the land, its people, and the sacred have vital roles to play in our contemporary thinking of ecological restoration. It will be critical to listen and not fall into the trappings of modern ideals, innovations, or hubris.