This week passed in a whirl of empire waistlines, girdles, and bonnets with plumes. I’ve decided on a topic for my research in philosophy of technology and women’s fashion magazines—identity. I hope to explore the ways in which technological changes have allowed for hyper-individualized identities as expressed by adherence to certain fashion trends. Through this exploration, I will gain a better understanding of how and why identities tended away from geographic location (such as ‘southern’) and towards more niche identities based on shared experience of race, sexuality, aesthetic preference, or value systems.

Going in chronological order, I began viewing the earliest women’s publications, starting in the late 18th century. I then continued through the 19th century. From about 1750-1865, publications were still relatively expensive. As a result, they focused on providing literary enrichment and fashion news for the elite, those who could read and afford to purchase the magazines. However, around 1865, magazines began to focus on a wider readership. Technological advancements of thinner, cheaper paper, “Linotype” letterpress setters, and advancements in replicating drawings all allowed for magazines to be produced for a middle-and even lower-class audience. The broader audience encouraged the use of advertisements to fund magazines. As a result, magazines became even cheaper as they were funded by advertisers rather than the full burden of production cost falling on the consumer.

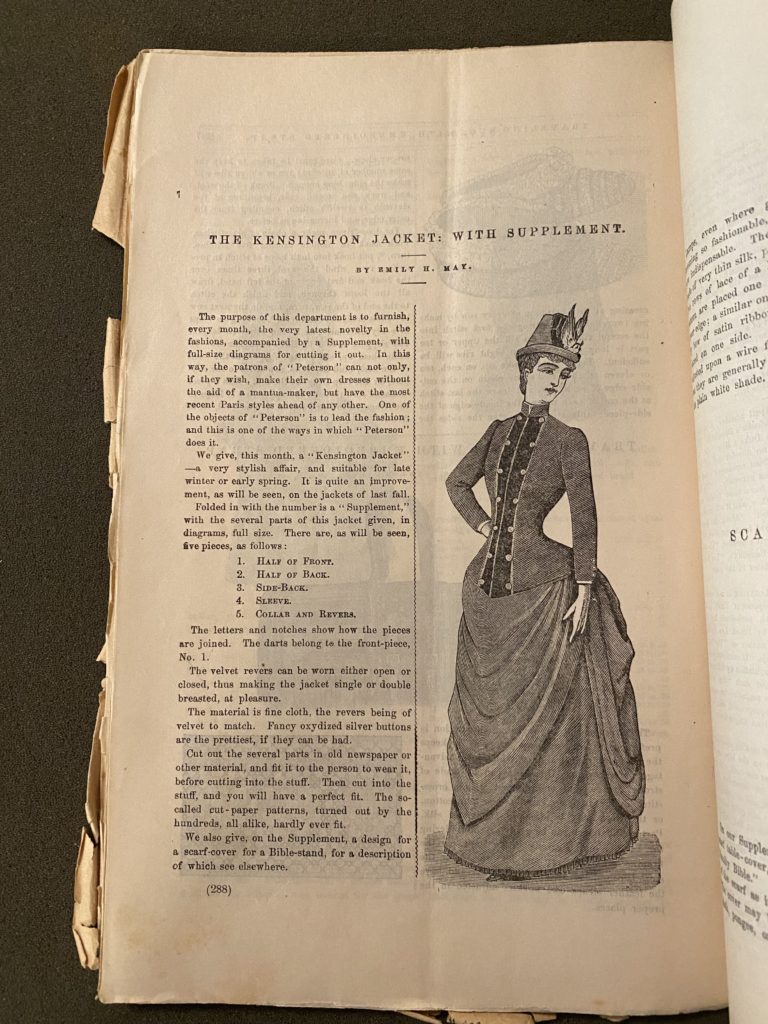

As a result of these technological innovations, content of the magazines began to target those who made their own clothes, rather than only women with dressmakers. Instructions for patterns began to appear in issues, such as the one below. It is from the Peterson’s Magazine March 1887 issue.

Another interesting technological change which impacted appeals to identity was the development of more vivid paints. Fashion plates were hand-painted, and as this process became more refined and elaborate over the course of the 19th century, more attention was devoted to coloring the skin of the women wearing the dresses. In 1845, the women (while still having a distinctly “European” look) lacked any distinguishing color beyond the occasional dot of red blush on the cheeks. By 1876, the women were cleared painted a vivid peachy shade. This shows that as technology advanced, the women were identified by race or skin color in the fashion plates.