Remarkably, this entry will be one of the final posts I write for this summer’s CCEPS fellowship.

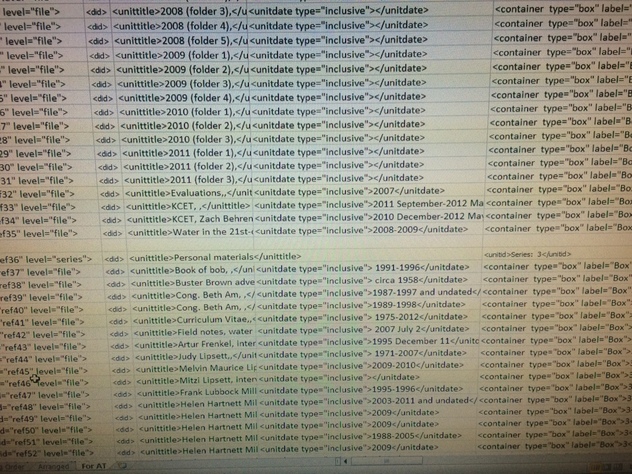

This week I worked on something completely new, signifying the final stages of processing the collection. Once I completed the foldering process, the next step was to transfer all of the info into Archivist Toolkit. Once this was done, I then had to arrange and review everything to make sure the collection was on its way to becoming ready and available for research!

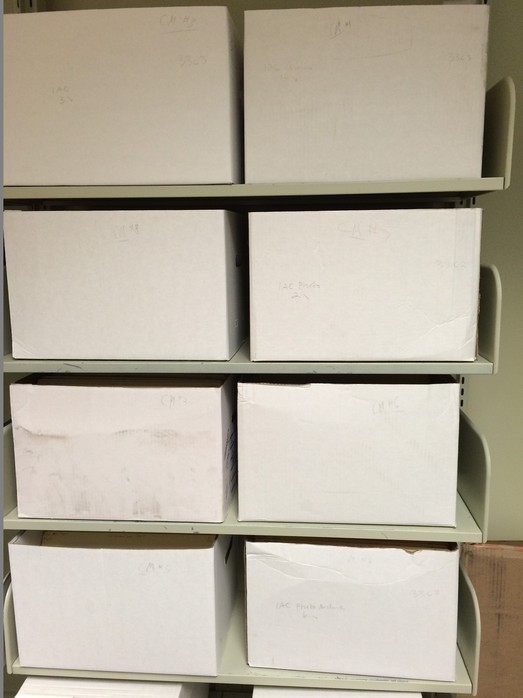

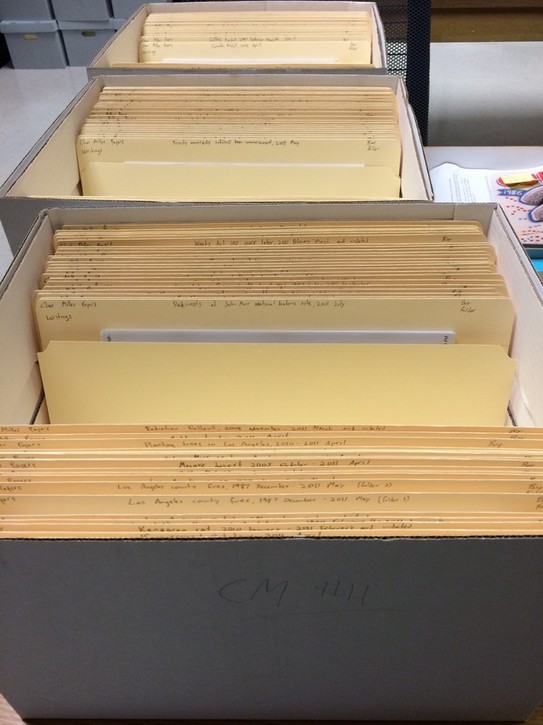

This entailed many steps, some of which I am still working on currently. I had to re-arrange some of the folders and move them into different boxes, based on space availability and making sure none of the folders would either move around too much because of too much room, or become folded and potentially compromised because the box was stuffed too tight. As it turned out, there was more room in most boxes than I had foresaw initially, and therefore had to place some more folders in each, causing a re-arrangement of sorts for the folder numbers of several folders. Thankfully, I was told not to write the actual box and folder number on the folder themselves until the very end of this process. Therefore, while I had to fix a lot of the information on Archivist Toolkit, at least I then completed the folders’ titles with the appropriate information – saving a lot of hassle, erasing, and extra labor!

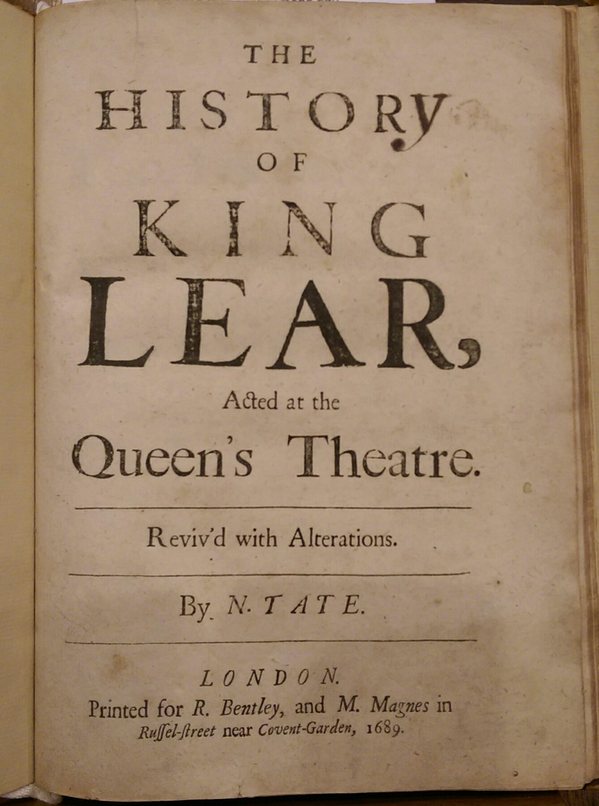

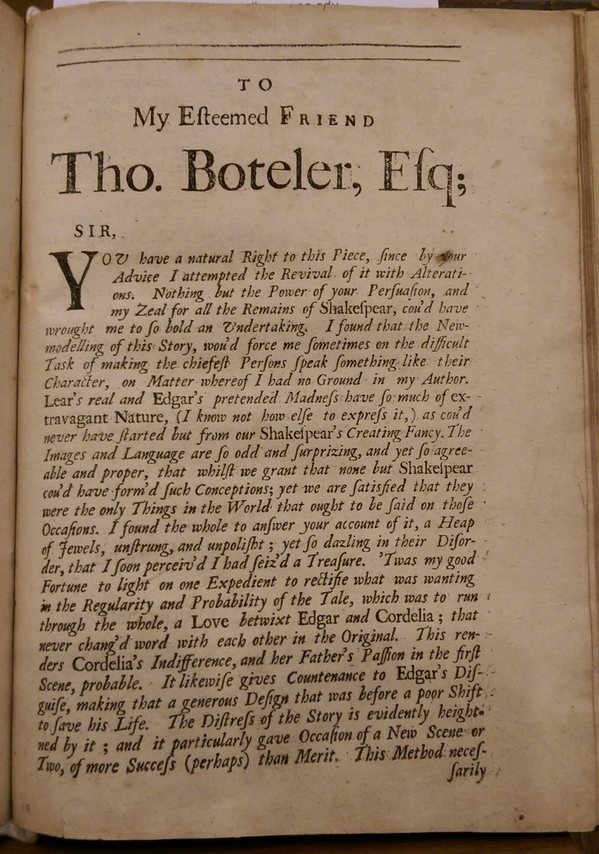

Now, I am working on the collection’s finding aid and Front Matter. It has been very interesting to learn as I go the proper ways in which to describe the various aspects of a collection and provide valuable details for future researchers. There is a template, thankfully, to use as a guide but I’ve had to read some of the guidelines and learn about the overall format prior to simply adding in the necessary information. This has truly provided a great learning experience in addition to the welcoming task of completing the processing of an archival collection on my own. It has also been neat to research a little further on Professor Miller’s career and notice some names of relatives, colleagues, and his published materials that I had come across multiple times while arranging the collection.

It will be extremely exciting to write the post next week, as I should be finishing up the work and therefore able to relay all of the information and lessons I learned while processing the collection, especially creating the finding aid, which will hopefully “tie it all together.”

Stay tuned!