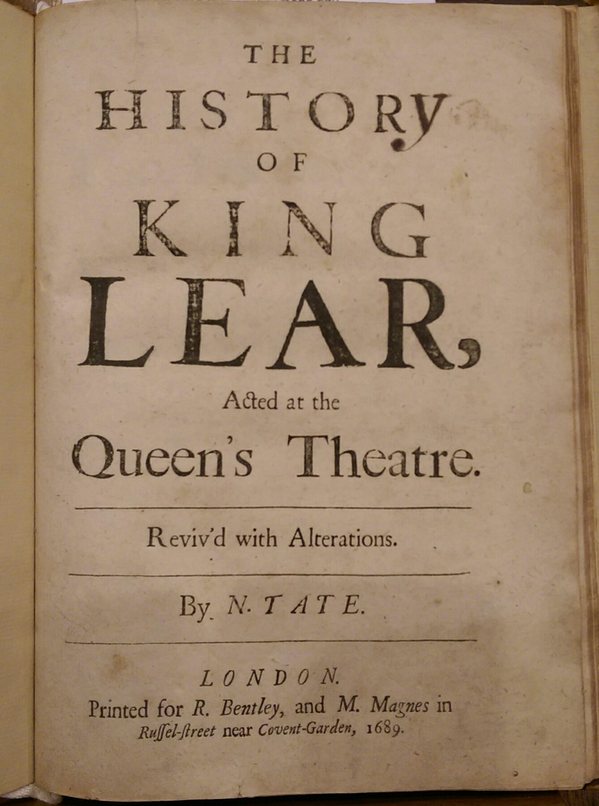

In 1681, Nahum Tate published his The History of King Lear, an adapted and revised version of Shakespeare’s play. It became the standard performance edition of Lear in England for over one and a half centuries, and yet it is infamously a radically different play; Tate took a number of liberties with the plot and characters to make the play more suitable for stage, and critics since the mid-19th century have widely panned his version as a result.

Special Collections has an edition from 1689, which I’ve been fortunate enough to start working with. Some of the text is faded at the corners, but overall it’s in great condition and is a fascinating (if perhaps frustrating) read.

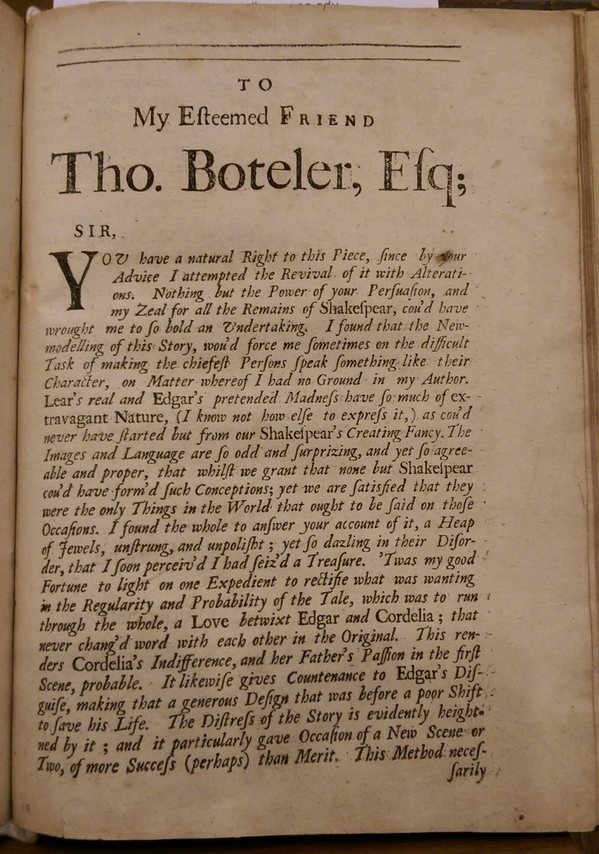

This edition begins with an “Epistle Dedicatory” from Tate. It begins with reverence and (perhaps disingenuous) apprehension: Tate had “the difficult Task of making the chiefest Persons speak something like their Character, on Matter whereof I had no Ground in my Author. Lear’s real and Edgar’s pretended Madness have so much of extravagant Nature…as cou’d never have started but from out Shakespeare’s Creating Fancy.”

While Tate dubs Lear and Edgar’s madnesses “extravagant” and praises their author’s singularity, he is in fact saying that he could have written their actions a bit better. He goes on: “‘Twas my good fortune to light on one Expedient to rectifie what was wanting int he Regularity and Probability of the Tale, which was to run through the whole, a Love betwixt Edgar and Cordelia.” Tate says this was necessary to render “Cordelia’s Indifference, and her Father’s Passion in the first Scene, probable.” Moreover, it would give “Countenance to Edgar’s Disguise, making that a generous Design that was before a poor Shift to save his Life.”

What Tate is really saying about the “extravagant Nature” of the character’s actions is that they were unrealistic or unreasonable. Edgar’s disguise is to be more understandable as a young man watching over his lover’s father; Lear’s rage is towards a stubborn daughter who won’t doesn’t wish to honor her house, through words or marriage. For Cordelia to show her father such disrespect (“Indifference”), he seems to imply, would require her to have a problem with being married off. The problem here, though, is that Cordelia isn’t actually indifferent; her original response is about modes and settings of expression, not substance; “Love, and be silent,” and “My hear’ts more richer than my tongue.” Tate strips these line from his edition, perhaps to make her indeed seem indifferent. But he has not solved the problem of her indifference through a love affair with Edgar. Rather, he attempts to create an indifference or bitterness towards Lear , changing her behavior entirely.

My personal favorite, the Fool, is missing from Tate’s version; part of my study of Tate will be to investigate how the Fool’s function of prophet and commentator is taken up by others in this version. The Irving Shakespeare indicates that directors found the Fool an unseemly character in the 1830s when the original was being revived. Perhaps Tate felt similarly, or perhaps he simply felt the Fool unnecessary.

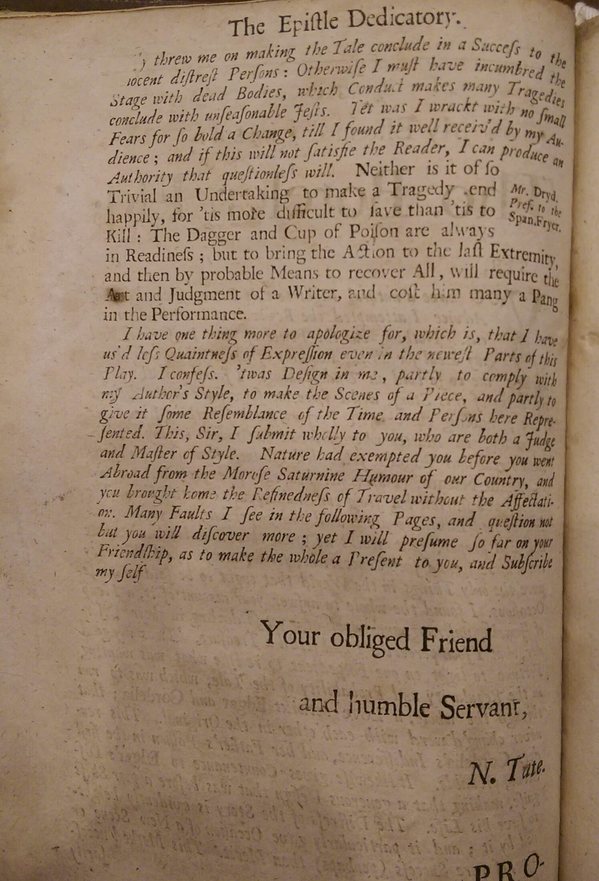

Tate makes one most significant change: famously, Edgar and Cordelia are married instead of the bloodbath of the original play; Tate writes that he did not want to “incumber the State with dead Bodies, which Conduct makes many Tragedies conclude with unseasonable Fests.” For, he writes, “’tis more difficult to save than to Kill: The Dagger and Cup of Poison are always in Readiness; but the bring the Action to the last Extremity, and then by probably Means recover All, will require the Art and Judgement of the Writer, and cost him many a Pang in Performance.” As with Lear and Edgar’s madness, Tate invokes probability as an important guiding factor in his process. But again we should ask: is a happy ending the most “seasonable” or likely result, or truly the more “difficult” resolution to Shakespeare’s original text? Or is it more reasonable only with Tate’s alterations? Tate does seem to ignore that he has created something wholly new; what is probably or seasonable in his text says nothing about what is probable or seasonable in Shakespeare’s.