0

0

1

162

928

Claremont McKenna College

7

2

1088

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

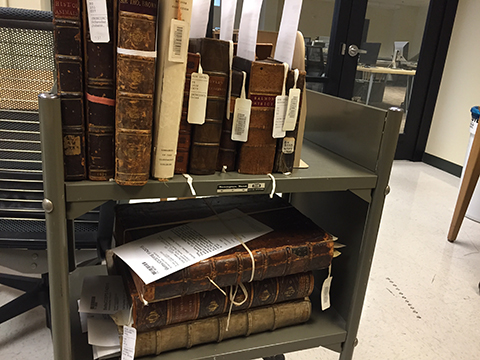

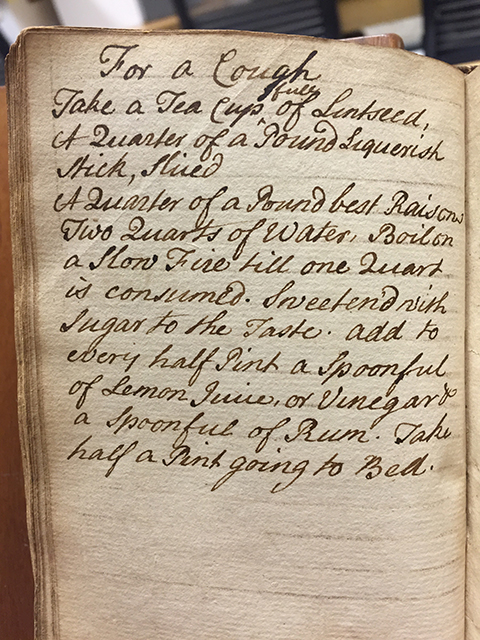

This week was more reading than I ever thought I was capable of.

I requested 11 new materials last week and, somehow, I actually was able

to go through all of them. The most challenging were definitely those in Latin and German; but I was able to get the gist of their contents by

translating chapter headings and some of the prefaces. The range on these

materials was pretty broad, but this gave me a diverse record of experiments

and proper research as well as some accounts that definitely sound more like

fiction than fact.

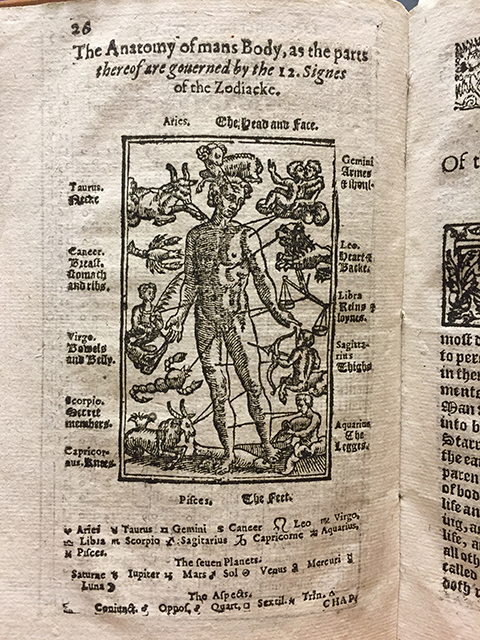

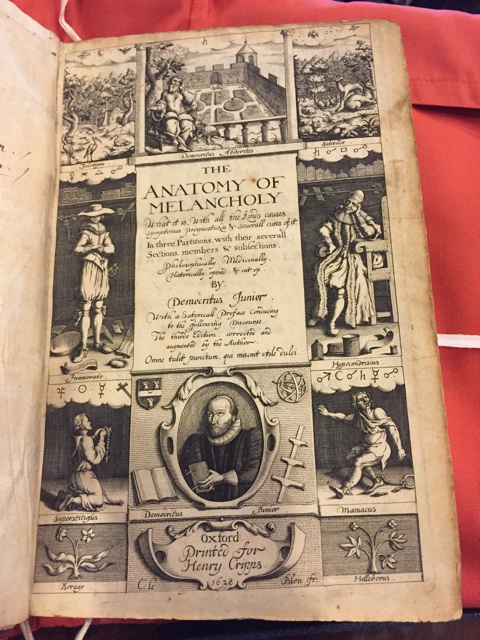

Before I jump into this week’s findings, I have to share that I

did find a 1628 edition of Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy last week. It’s

a fascinating collection that is more literary than scientific in many ways.

Burton focuses on the science of the humors, which leads to discussion on

what causes changes in the different humors, from physical ailments to more

spiritual/emotional factors. I will definitely have more to tell about

this work, as I intend to spend more time with this material, possibly for

thesis purposes.

Cover plate from The Anatomy

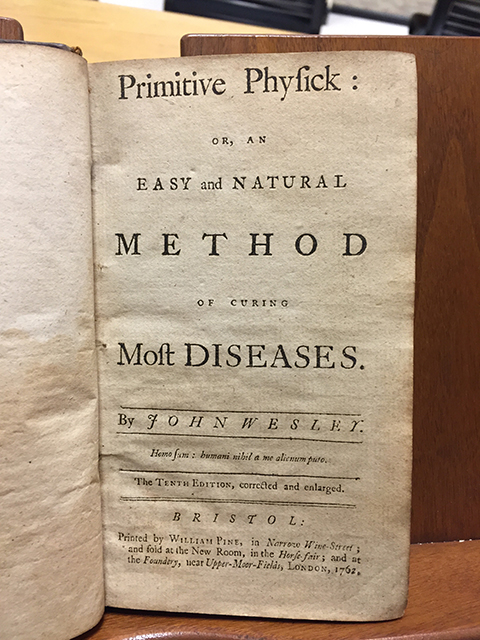

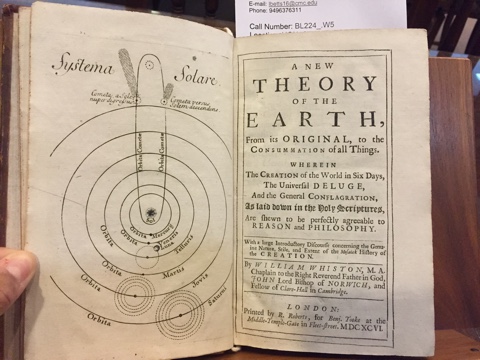

One material that was really interesting to me was A New Theory of the Earth by William Whiston. I had a later edition that was printed in 1696. By this time, Whiston had already established himself as another voice trying to reconcile science and Revelation. As a science work written by a chaplain, this reminded me of Primitive Physick. It included theories surrounding creation and “the deluge” (Noah’s flood), both concerned with comets and other heavenly bodies. Whiston also included plenty of scripture references scattered throughout his explanations.

Cover plate of A New Theory with illustration of the solar system

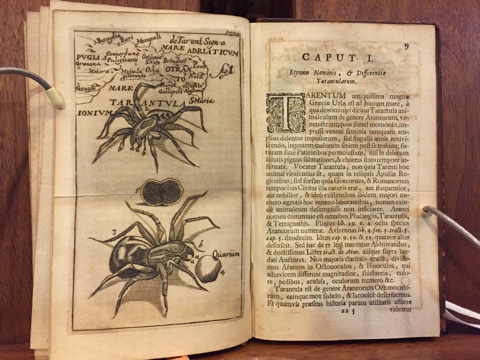

Something that was quite new to me this week was translating some of these materials. Well, I can’t say it was completely new because I did take multiple years of Latin way back when. But still, I had expected all my materials to be in English. One inevitable product of translating was the surprise of realizing what the book was actually about. An example: Opera Omnia Medico-Practica Et Anatomica by Georgio Baglivi seemed at first to be mainly about practical medicine. That’s what its first book was concerning, and the title itself translates to “The Complete Works of Medical Practice of Anatomy.” What a surprise to find that the whole second section was devoted to “The Anatomy, Bite, and Effects of the Tarantula.” Apparently, “tarantism” was a thing back in the early modern era and it was a disease thought to be caused by the bite of tarantulas, which were believed to be the most poisonous spider mostly because of their size. There’s a phenomenon I will definitely be reading up on in my free time!

Who doesn’t love stumbling upon spider illustrations while innocently perusing through medical literature? Illustration from a 1719 edition.

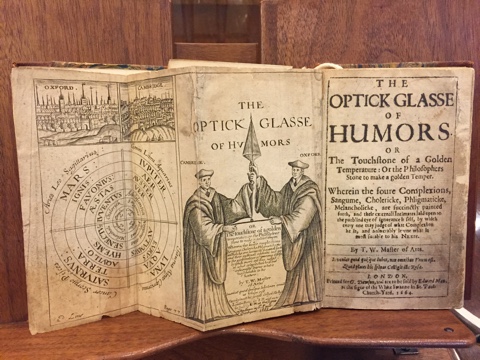

Another interesting pattern I noticed throughout many of these materials were pull-out illustrations and diagrams. Many of these were for explanations of tools and methods for distillation or larger diagrams of cosmic orbits. I thought it was interesting to have these tangible additions to the textual information, and it adds to the narrative of the binding and printing of the book itself.

The cover pages of a 1664 edition of The Opticke of Humors, including its own pull out with a more elaborate title page and diagram of the planets.

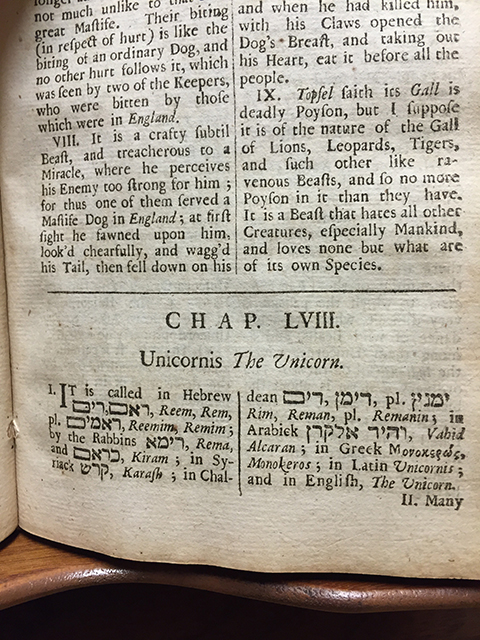

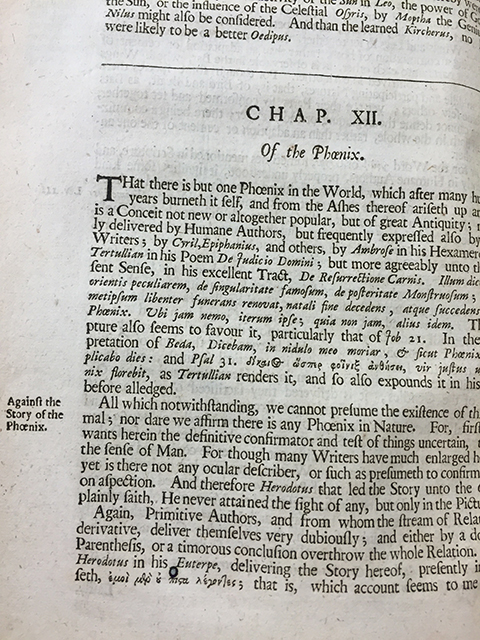

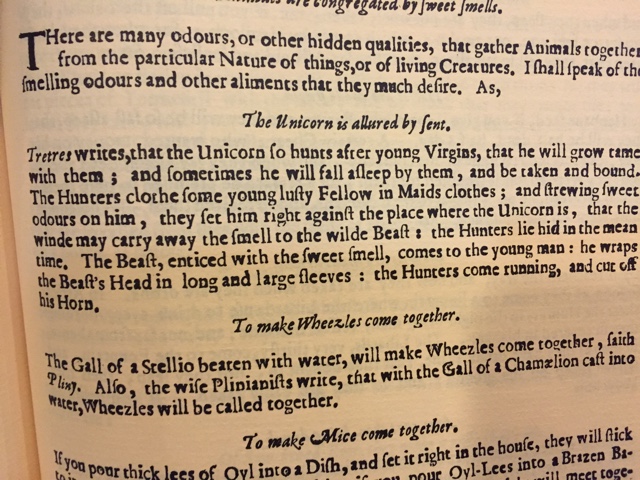

And now for my most favorite material of the week: Natural Magick. I don’t know what it was, but this was the most amusing thing I’ve read so far during this project. John Baptista del Porta covers a huge range of topics, from scientific to ridiculously obscure, including the proper cooking of peacocks and how to beautify women (from dying hair to clearing blemishes). My favorite was a chapter in his (literally) “random experiments” section that described how one might alter his appearance so his friends won’t recognize him. I looked through a facsimile of a London edition from 1658; although he published his first edition in the late 1500s, this one still shows traces of the strong mythical influence of earlier science. One section of hunting and gathering animals included advice on capturing the unicorn, of course.

The above mentioned passage. But I had to also include the part about how to “make Wheezles come together,” because how could I not?