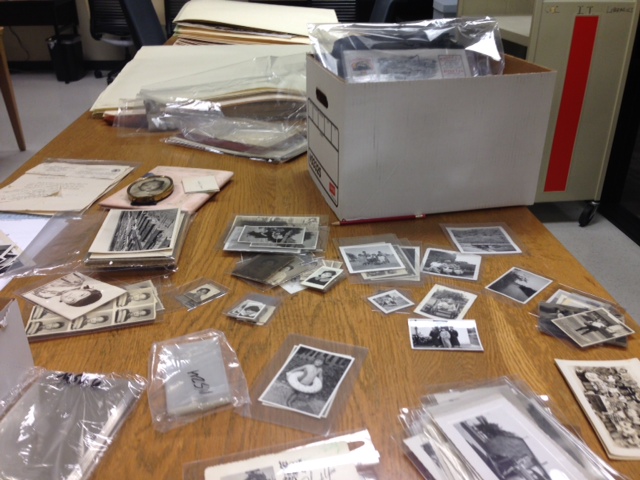

I am happy to announce that I have begun processing a new, 14 box collection: the Nag Hammadi Codices Project (NHCP) files. That is basically a fancy way of saying that Special Collections has accessioned an amazing group of documents and images, most of which are related to the publication of the Nag Hammadi gnostic text library.

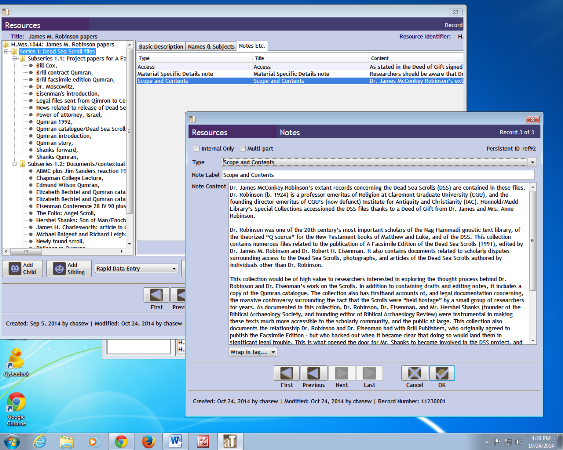

Although the topic and the records are fascinating, we were dismayed to find that before they arrived at their new home here, they had not been stored in the best of conditions….by which I mean they had been stored in a garage. And although garages are an amazing and wonderful thing, trust me when I say they aren’t an awesome place to put your precious records. Why? Because you will likely end up with mold, bugs, and water damage all over the lovely things you were trying to save!

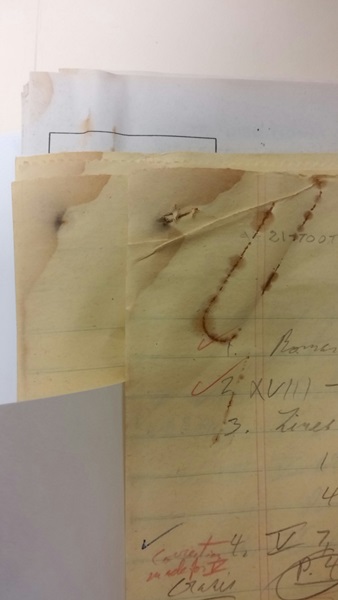

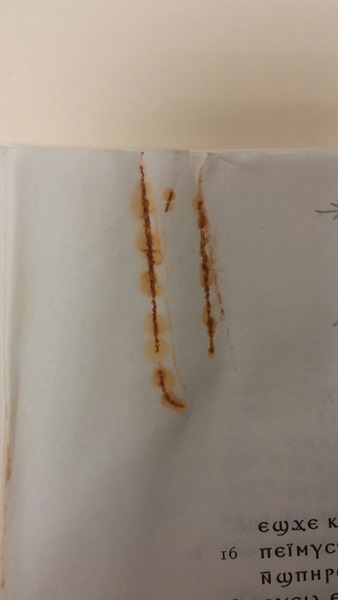

Now, when I think of water damage, usually what pops into my head is crinkled up pages of paper (what you would encounter if you were to drop a book in the bathtub). Well, it turns out that in addition to wrinkling pages, water can also cause rust! And then you end up with things like this:

Yes: that, my friends, is the picture of what a rusting paperclip left on a stack of documents for years will leave you to remember it by! Needless to say, I spent a fair amount of time removing rusty paperclips and staples from this collection’s contents this week. There’s no way those rusty little suckers are heading into the archives if I can help it!

My time-consuming encounter with rust this week made me wonder about the chemistry of this interaction. So I looked it up. It turns out that – of course – paperclips are made of steel, and steel is derived from iron. Over time, as iron and oxygen meet and mingle, a chemical reaction takes place which transforms the iron into iron oxide. The common term for iron oxide is rust.

The good people who make paperclips know this, and so to try and prevent it, they coat paperclips in a layer of zinc. This works – until the zinc layer erodes due to humidity, water saturation, etc. (Many thanks to Shaun McGonagal over at eHow for this explanation! See http://www.ehow.com/facts_5730689_do-paper-clips-rust_.html for more information.)

Which brings us full circle to why you don’t store documents in a garage. Garages, generally speaking, are not weather-proofed…and that means water and/or humidity will hit all your paperclips…and then you will open up a box in 30 years and find this:

But all is not lost! Fortunately, Special Collections accessioned these documents in time to halt their disintegration…so they will be around for a long time, and many researchers will get to enjoy them. Still – I thought after learning all this it was worth using my weekly blog post to make a public service announcement about rust!

Happy storing (your documents somewhere other than a garage) :-).