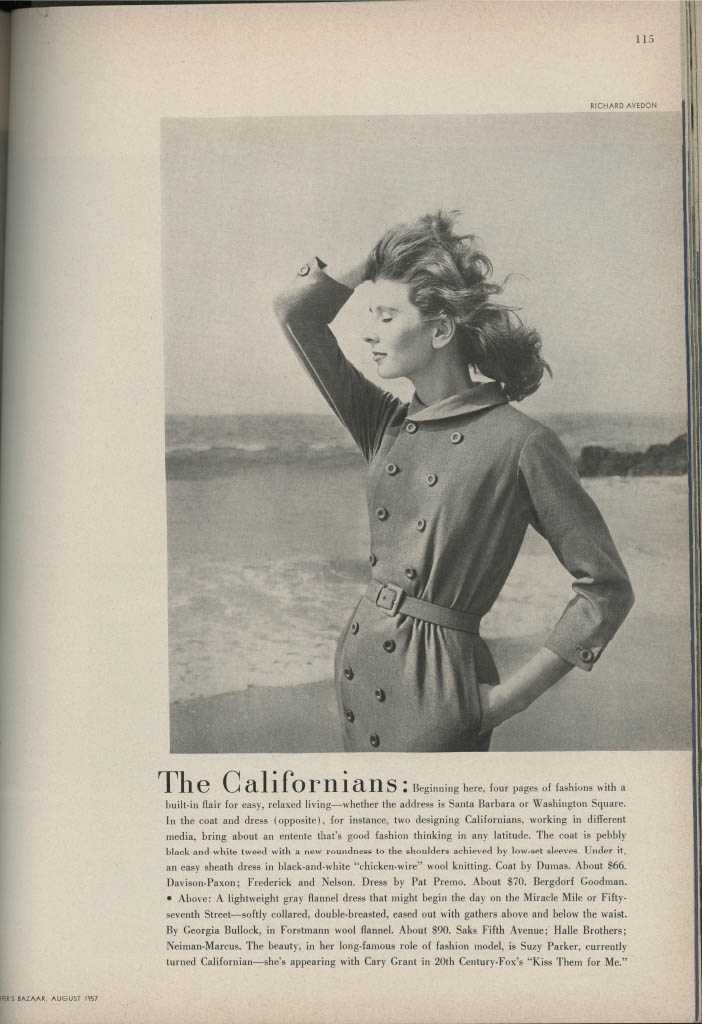

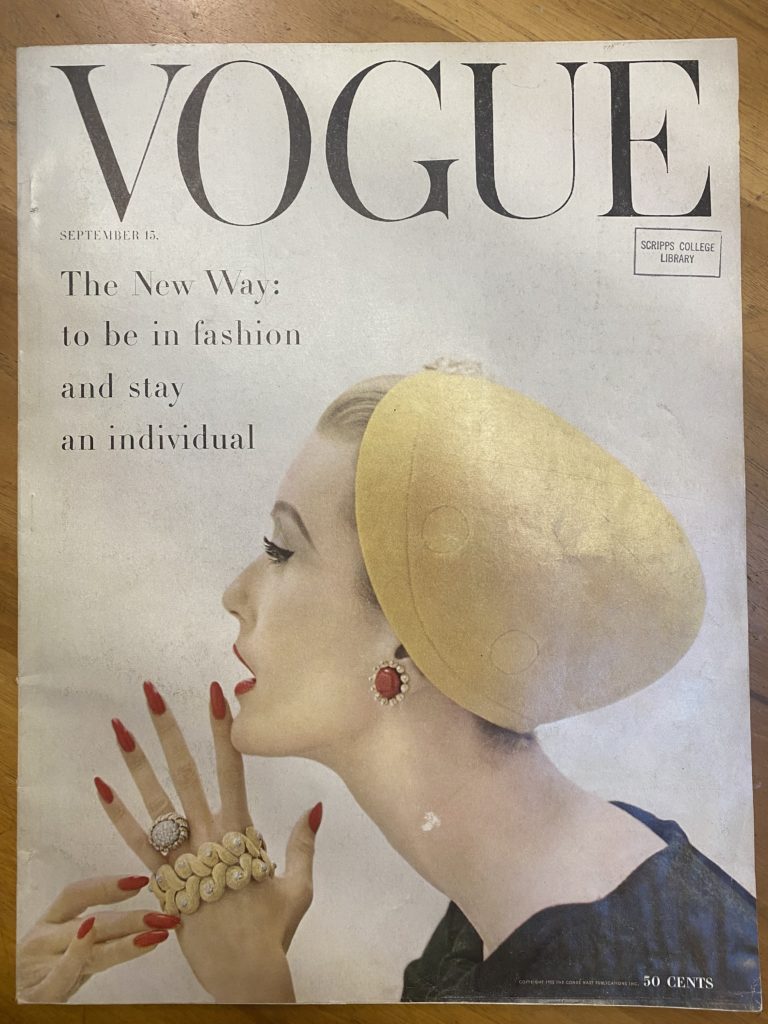

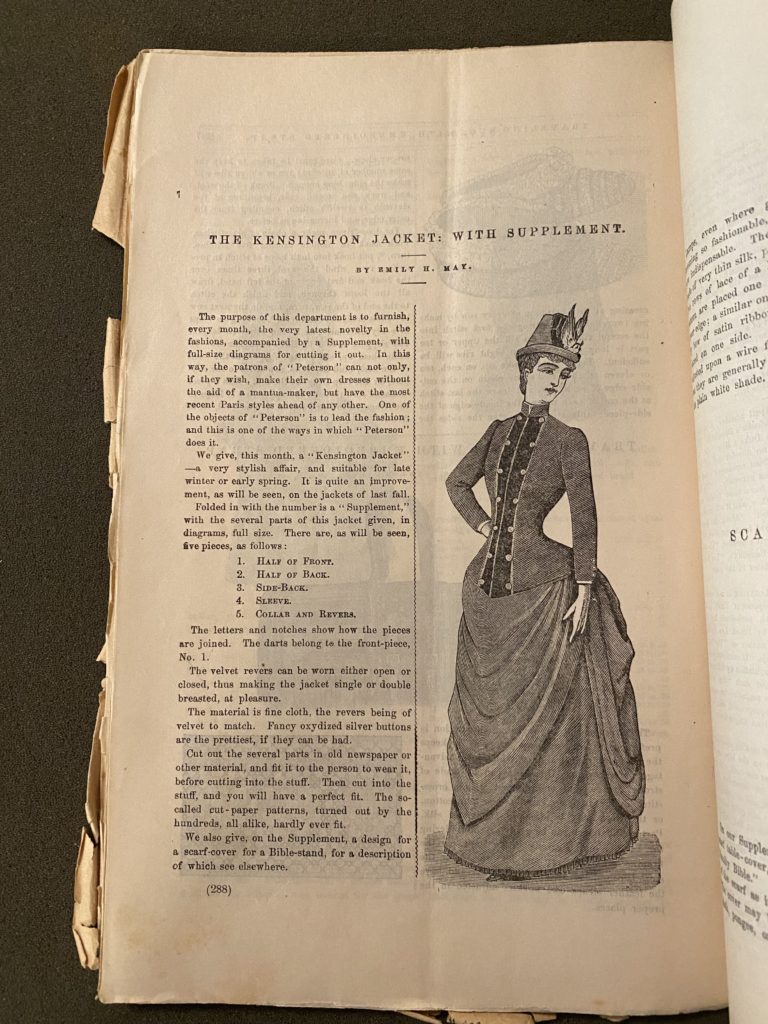

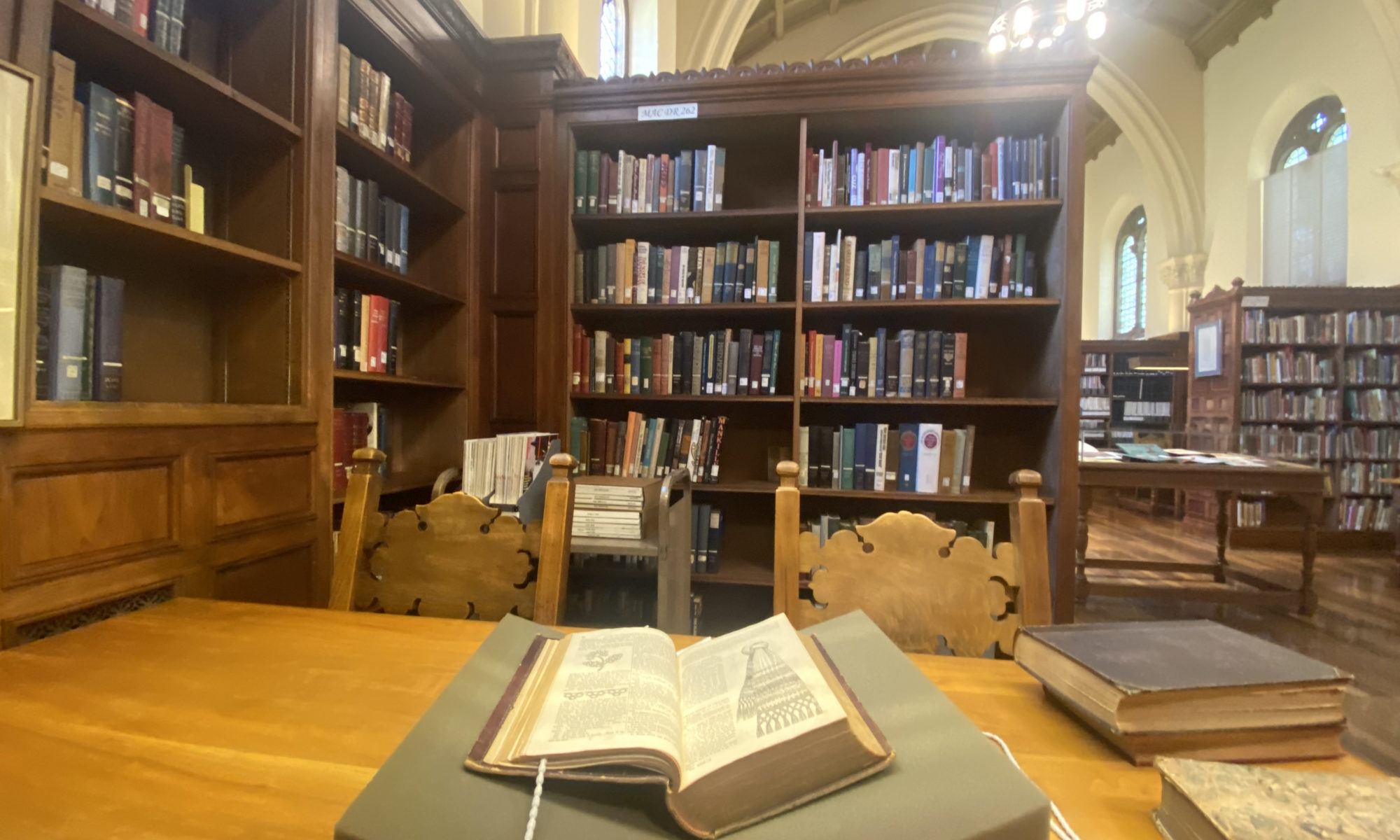

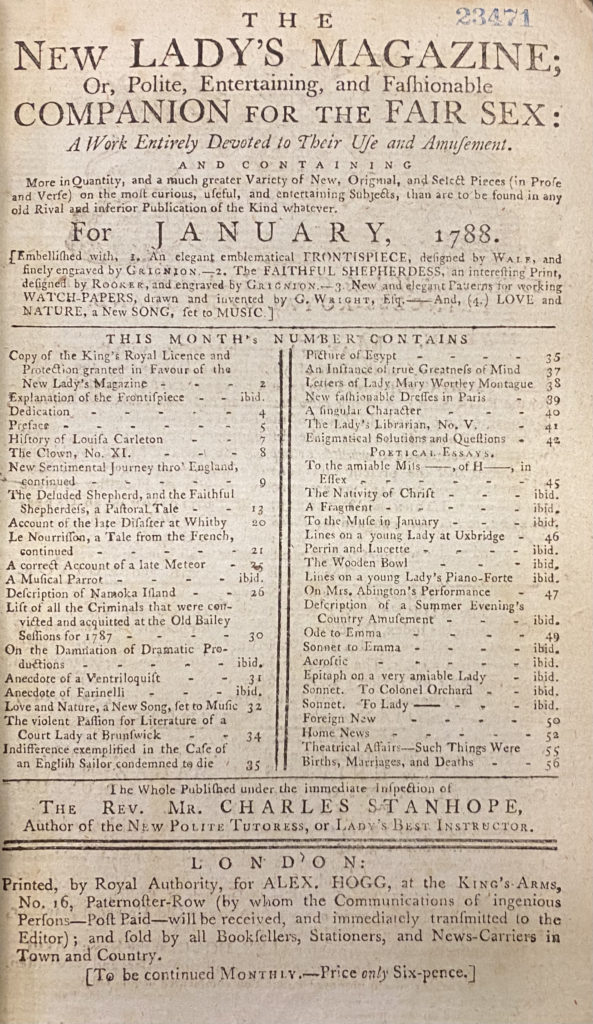

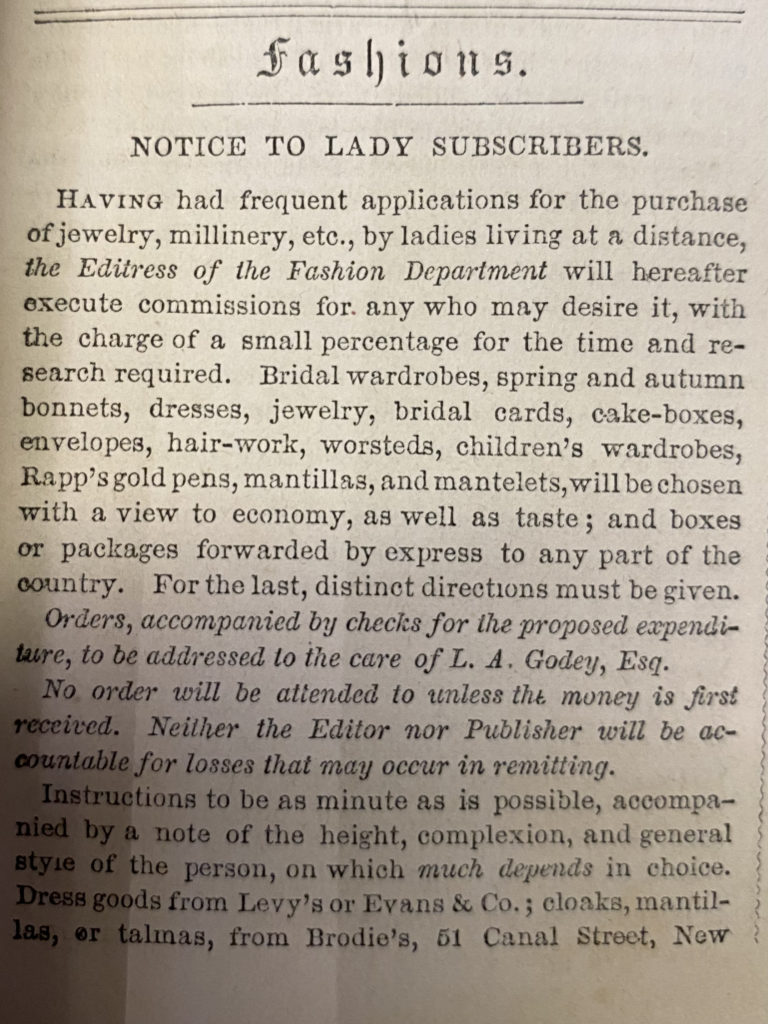

This week, I put the finishing touches on my exhibit and published it to the CCEPS Omeka website. Wrapping up the project, I get to reflect on the experience of engaging with primary sources, digitizing them, and presenting them to be read by the public. After this summer, I feel much more equipped to complete humanities-based research. I’ve learned how to review literature and find relevant secondary sources and databases. More interesting, however, is the new perspective I gained towards the process of data analysis. As a statistics student, I work a lot in large sets of raw data. The primary sources are, in many ways, like that raw data. To researchers, by themselves, large volumes of magazines are very difficult to interpret without first deciding which data is most important to look at, and what they are looking for within that data. They then must come up with a process for organizing and analyzing the data.

We, as researchers, get to influence truth by framing and choosing which data to include and deem relevant in our projects. We can seek to process materials responsibly, but we must also recognize our biases going into projects. I wanted to find a point to prove when I entered this project, but I learned that the data was far too large, expansive, and incomplete to prove one large point. If I want to continue my research in the future, I must find more qualifiable and specific data to trace a specific phenomenon. I home that through my broad framing of the primary source data available at the Claremont Colleges Library and Ella Strong Denison Library, I can encourage others to access the materials which will hold so many answers when we learn to ask strong questions.