While working with the Irving Wallace papers, I have come across more than a handful of books on the writing process. At first, I thought it would be great to see what kind of writing advice prolific authors like Wallace turned to when they needed help. And, while that would be interesting and perhaps one or two of the titles have turned out to be for that purpose, Irving Wallace collected these books for a completely different reason.

On several occasions, Wallace discovered that excerpts from his own writing appeared in books on writing advice and even in textbooks. This clearly pleased him well. One example is Karl K. Taylor and Thomas A. Zimanzl’s Writing from Example: Rhetoric Illustrated. The Honnold Mudd Special Collections acquired this book as part of Irving Wallace’s series for his book The Sunday Gentleman. I opened the book to see what sort of advice it might offer, but discovered Wallace’s inscription, “An excerpt from The Sunday Gentleman on pages 6 to 10.” Rather than offering advice TO Wallace, this book offers advice BY Wallace.

On another occasion, I wondered what reason Wallace could possibly have for possessing a junior high school-level textbook on reading. Here again his inscription reveals the purpose. In the front cover of this book, Wallace wrote, “My Dr. Joseph Bell story, condensed from The Fabulous Originals, appears here in a junior high school text book – pages 226-232.” Again, his work is offered as advice to other would-be writers.

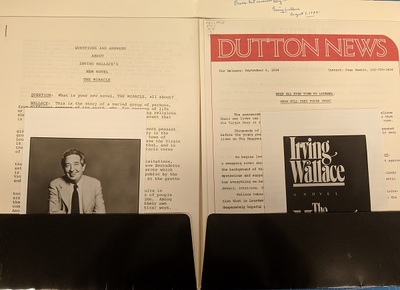

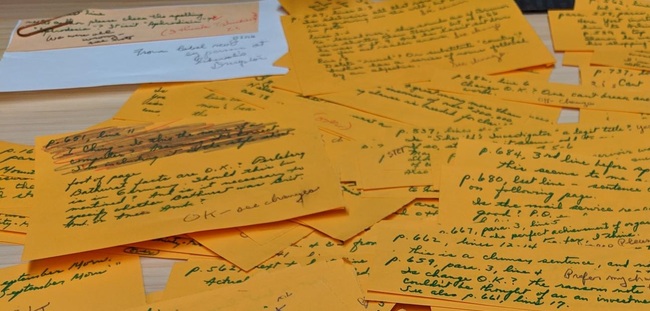

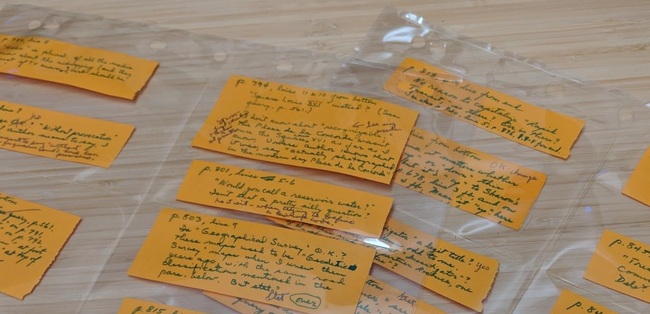

What does this all have to do with going to the archives, you ask? The information I have just related is only available to those who physically go to the archives and hold these books in their hands to read the inscriptions that Wallace wrote. Otherwise, one might easily assume, as I did at first, that these texts served Wallace as writing advice for the work he produced. Knowing that these texts instead feature Wallace’s work for others provides for an entirely different kind of interpretation of Wallace’s work. Irving Wallace wrote some kind of note or explanation in the front of every single book (other than copies of his own works) that he donated to the Claremont Colleges Library. In fact, he wrote a short note of explanation for nearly every single item in the multitude of items donated. Manuscript drafts have notes explaining which draft number, who edited and read it, and whether the written comments are from Wallace or someone else. Notes on letters or other correspondence briefly provide context for the exchange. Galley copies often have notes explaining which is the first or the final galley and whether it was sent to the publisher or straight to the printer.

In thinking through his donations while he was still alive, and how he hoped people might use his work, Irving Wallace provided a vast amount of interpretive material. It is clear that he hoped seeing examples of his work at various stages would be useful to people. He also hoped that his research notes, memorabilia, and correspondence would be enlightening to his life and works and all of the people who helped him along the way.

It is only by going to the archives to look at the information that the finding aid and/or digitized excerpts cannot possibly include that one truly learns about their research subject. In his simple reflections, contexts, and notes Wallace revealed his love and devotion to his family and friends, his joy in learning and sharing what he knows, and his drive to tell a great story–the thing he wanted more than anything in life.