Funny thing happened this week. While entering the Seymour Papers’ finding aid into the library’s records system. I had to double checked the written directions given to me because I could not remember how to do something. While reading the directions, it stated that the selection I clicked should have auto-populated the information I needed. I had a moment of panic because nothing auto-populated!!! Surely I must be doing something wrong! I moved onto task 2 and the same thing happened! As someone who HATES doing something incorrectly I quickly shot off an email asking for help. Turns out the part of the directions that stated information would be auto-populated was outdated. When changing the directions from how to use the old system to how to use the new system, this one sentence accidentally got left behind. Luckily the instructions can now be updated so that way future fellows won’t suffer momentary heart failure.

What the Irving Wallace Papers Teach About the Importance of Archives

While working with the Irving Wallace papers, I have come across more than a handful of books on the writing process. At first, I thought it would be great to see what kind of writing advice prolific authors like Wallace turned to when they needed help. And, while that would be interesting and perhaps one or two of the titles have turned out to be for that purpose, Irving Wallace collected these books for a completely different reason.

On several occasions, Wallace discovered that excerpts from his own writing appeared in books on writing advice and even in textbooks. This clearly pleased him well. One example is Karl K. Taylor and Thomas A. Zimanzl’s Writing from Example: Rhetoric Illustrated. The Honnold Mudd Special Collections acquired this book as part of Irving Wallace’s series for his book The Sunday Gentleman. I opened the book to see what sort of advice it might offer, but discovered Wallace’s inscription, “An excerpt from The Sunday Gentleman on pages 6 to 10.” Rather than offering advice TO Wallace, this book offers advice BY Wallace.

On another occasion, I wondered what reason Wallace could possibly have for possessing a junior high school-level textbook on reading. Here again his inscription reveals the purpose. In the front cover of this book, Wallace wrote, “My Dr. Joseph Bell story, condensed from The Fabulous Originals, appears here in a junior high school text book – pages 226-232.” Again, his work is offered as advice to other would-be writers.

What does this all have to do with going to the archives, you ask? The information I have just related is only available to those who physically go to the archives and hold these books in their hands to read the inscriptions that Wallace wrote. Otherwise, one might easily assume, as I did at first, that these texts served Wallace as writing advice for the work he produced. Knowing that these texts instead feature Wallace’s work for others provides for an entirely different kind of interpretation of Wallace’s work. Irving Wallace wrote some kind of note or explanation in the front of every single book (other than copies of his own works) that he donated to the Claremont Colleges Library. In fact, he wrote a short note of explanation for nearly every single item in the multitude of items donated. Manuscript drafts have notes explaining which draft number, who edited and read it, and whether the written comments are from Wallace or someone else. Notes on letters or other correspondence briefly provide context for the exchange. Galley copies often have notes explaining which is the first or the final galley and whether it was sent to the publisher or straight to the printer.

In thinking through his donations while he was still alive, and how he hoped people might use his work, Irving Wallace provided a vast amount of interpretive material. It is clear that he hoped seeing examples of his work at various stages would be useful to people. He also hoped that his research notes, memorabilia, and correspondence would be enlightening to his life and works and all of the people who helped him along the way.

It is only by going to the archives to look at the information that the finding aid and/or digitized excerpts cannot possibly include that one truly learns about their research subject. In his simple reflections, contexts, and notes Wallace revealed his love and devotion to his family and friends, his joy in learning and sharing what he knows, and his drive to tell a great story–the thing he wanted more than anything in life.

Back from Vacation for the Presentation

After spending 2 weeks abroad, I quickly got thrown back into work when I found out my final CCEPS presentation had been scheduled for my second day back to work. So

The Prize Controversy

In a plot twist that sounds more like one of Irving Wallace’s novels than his own life, the author got a taste of excitement following the release of The Prize. Briefly, the novel is about the ceremony for the annual Nobel Prize. From the book cover, “Six people all around the world are catapulted to international fame as they receive the most important telegraph of their lives, which invites them to Stockholm to receive the prize. This will be a turning point in their lives, in which personal affairs and political intrigue will engulf every one of the characters.”

Although Wallace was meticulous in his research, a reviewer in Norway took issue with how Wallace portrayed the Nobel Prize institution and its judges, calling the book a scandal and accusing Wallace of “declar[ing] war on Scandinavians.”[1]

A rather heated exchange took place through letters and newspaper columns and responses in which Wallace defended his research process and called on witnesses to vouch for him. In one set of Wallace’s notes he stated, “I interviewed [Dr. Anders Osterling] September 23, 1946. He was extremely frank. Among other things he told me that he fought against Pearl Buck receiving the Nobel Prize, that Bunin got it to “pay off” for the omission of Tolstoy and Chekhov, that Thomas Wolfe, Somerset Maugham, James Joyce were never nominated, that Frost, Upton Sinclair, Dreiser were long ago considered and voted down. He felt Mann deserved the prize twice.”[2]

Despite a good many people, including Dr. Osterling, coming to Wallace’s defense, the eventual fall-out of the controversy over his novel resulted in his book translation being rejected in Copenhagen, and by multiple publishers in Norway. The controversy seemed to finally blow over, but as recently as 1985, debate continued to ensue with the release of the major motion picture starring Paul Newman and Elke Summers in the Scandinavian countries.

References

[1] Anonymous,

“U.S. Author Declares War on Scandinavians,” in the Eagle, Wichita, Kansas, 20 September 1962.

[2]

Irving Wallace, “untitled note,” 1962, Box 28, Folder 13, Irving Wallace Papers, H.Mss.1076. Special Collections, Honnold Mudd Library, Claremont University Consortium.

Off to London

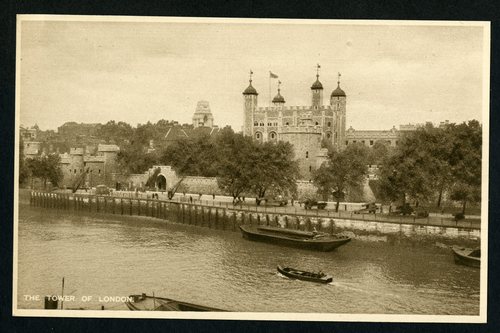

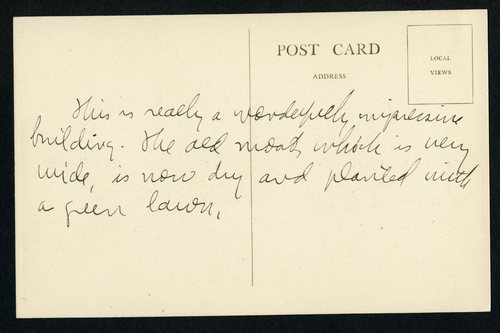

Tomorrow evening this archivist takes off to explore Europe for the next 2 weeks. A few of my days will be spent in London. I thought this made an excellent opportunity to share one of the postcards John Laurence Seymour brought back from his European trip in 1922/1923.

Seymour would purchase post cards as souvenirs to keep for himself, and frequently made notations on the back of them with personal descriptions and anecdotes. Below is a postcard of the Tower of London with Seymour’s notations on the back included.

The Author Press Kit

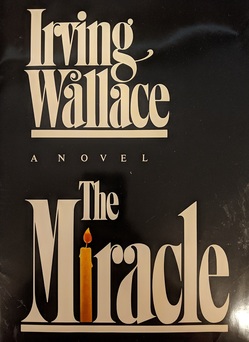

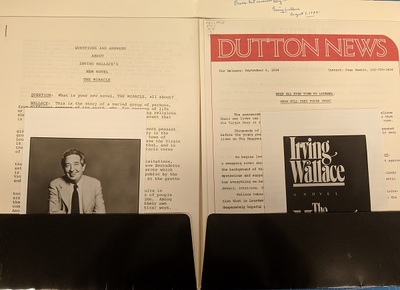

Have you ever seen an author press kit? Me neither. At least I hadn’t until I noticed a copy of Irving Wallace’s press kit for his novel, The Miracle. Produced by Wallace’s publisher E.P. Dutton, Inc. in New York, the kit was meant to be sent to book sellers both to entice them to order the book for their retail locations, but also to provide stock material those potential book sellers could use to sell the book in their stores.

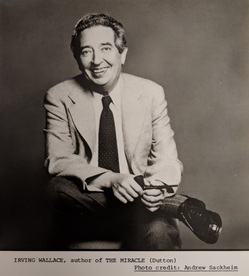

The press kit arrives in a glossy 8.5″x11″ folder using the same fonts and imagery as the novel’s cover. Inside the kit are two pockets, one on each facing cover. In the left side, the kit includes the text of an interview with Wallace about his new novel. The interview, often titled “Questions and Answers” is a common feature of book publisher publicity and promotional materials. The Q&A interview is created for every single book whether or not a full press kit is developed. Additionally, the left-hand pocket includes a 5″x7″ glossy black and white image of Irving Wallace looking particularly authorly (Yes. I just made that up. Go with it.) in his suit and tie and holding his signature pipe. His smile is friendly and affable if not somewhat goofy (in a good way). The photographer managed to capture an image of Wallace in which he looks a respectable professional, but also relatable.

On the right-hand side of the folder, the pocket contains three more items. The first is a glossy 5″x7″ black and white photo of the book’s cover. Next is a press release from Dutton providing the sales pitch for the book with a synopsis description that hooks the reader (the back cover text as well). The “Dutton News” also lists the main cast members of the book and the requisite price, ISBN, Publication date, and so forth. Finally, behind the press release is a 3-page biography of Irving Wallace highlighting his long and varied writing career and impressive bibliography of magazine articles, short stories, fiction and non-fiction works to date.

Since the press kit for The Miracle was produced in 1984 with the release of the novel, I imagine that press kits have changed significantly in the digital era. Although today’s press kits likely include much the same information, it is, no doubt, sent electronically rather than physically through the good ol’ snail mail. That’s too bad, really. Having gone through this press kit I think there is something particularly endearing about the physical artifact–its tactility: the smooth, glossy surface of the folder; its smell: the faint chemical smell of the photo emulsion and the smell of good quality paper with actual typed ink; and its visual appeal: the document design of each item included, the photographic evidence of a real person and a real book and even the sense that you’re holding the essence of the book in your hands with the kit cover echoing the novel cover. All of these are part of what makes us still buy physical books even when we own electronic readers, cell phones and tablets that double as readers, and a host of other digital equipment that lets us “read” a book today.

Secondary Sources

When processing an archival collection, generally, you are dealing strictly with primary sources. While that is a fantastic experience, sometimes some secondary sources can be incredibly helpful to help one synthesize and put into context the files upon files of documents.

One of, if not the, best secondary source about John Laurence Seymour is a chapter from a book about Mormons at the Metropolitan Opera, written by Glen Nelson. The chapter “Digging Up the Pasha’s Garden” looks at both Seymour and his experiences related to his opera, In the Pasha’s Garden, performed at the Met in 1934/1935. I have found the chapter particularly helpful in writing the finding aid for the John Laurence Seymour Papers, and I would highly encourage others to read this chapter as well.

“My first published book”

Although Irving Wallace published his first article at the age of 15 and had many articles and short stories published early in his career, his first book was not published until 1955 when he was a tender 39 years old. Interestingly, for an author who became known for his fiction novels, screen plays, and movie scripts, his first publication The Fabulous Originals was a nonfiction book.

It would seem that Mr. Wallace had the golden touch from the get-go as he was offered an impressive $1000.00 advance (for 1954 anyway) from Alfred A. Knopf. His book was well-received and sold some 12,000 copies in its first printings.

Reviewing his work for the purpose of donating his papers to the Claremont Colleges Library in 1978, Wallace noted, “I was on my way–and doing what I wanted to more than any other thing in life.” How satisfying it must be to look back on a prolific career of “best-selling” publications and still know that there is no other thing in the world you would rather have done or be doing–still.

As I continue to work through streamlining the Irving Wallace Papers, I learn more and more about a man who lived an exciting life of travel, research, and writing. A life I would love to have more than any other thing in life.

Cheers, Mr. Wallace!

Opera Advertisements- Part 2

Last week I promised for a solution for the over-sized posters, and luckily we worked something out. The large posters that are too big for even the map drawers will be folded either in half (or in quarters based on how giant the poster is). The goal is basically to have as few folds as possible. Then, we will make custom sleeves for each folded poster out of Mylar, in order to help prevent any further damage and to keep pieces which have ripped off together.

Those sleeved posters will then go into a giant file with all of the other over–sized posters from this collection, and placed safely in the map drawers. Sadly, because these posters are so large and fragile, there is really no way to safely scan them with the resources we have here at the library…. However I was able to take a photo of one of the larger and more delicate posters with my phone, which is the photo below. The poster is from around the turn of the century and advertises an opera titled, “Adriana Lecouvreur”.

What Does It Mean To Research a Novel?

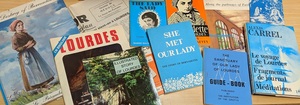

While working with Irving Wallace’s files for his book titled The Miracle, I was quite impressed with the research that went into the novel. I wondered what exactly it meant for a national best-selling author to conduct research. Consider this: Wallace apparently became interested in the miracles reported in Lourdes, France in the early to mid- 1930s. He published an article in 1936 in The Modern Thinker on “Miracles of the Mind.” The article takes the Holy Cross Cemetery of Walden City, Massachusetts as its subject to consider the psychology of cures and he also makes mention of the Grotto at Lourdes and the idea of miraculous cures. In a sense, he was already keen to know the difference between “miracles” and “cures.”

Fast forward to the 1970s. Wallace once again takes up the idea of the miracles at Lourdes and begins reading all of the published works about it. He starts with Lourdes by Emile Zola, written in French in 1894. Wallace photocopies the two-volume English translation borrowed from a university library and begins to outline the work in order to create a summary or abstract. He then diligently types up 17 pages of single-spaced notes focused on the story of Bernadette and the miracles at Lourdes. Next, he does the same for Alan Neame’s The Happening at Lourdes–38 pages of notes; Robert Hugh Benson Lourdes–16 pages; D.J. West Eleven Lourdes Miracles–20 pages; Franz Werfel The Song of Bernadette–17 pages; J.H. Gregory (translator) Bernadette of Lourdes–14 pages; and finally Edith Saunders Lourdes–26 pages of typed, single-spaced notes.

Wallace’s notes list a page number and a summary of the important information in his own words. What he summarizes is very specific:

- Historical context–what was happening in the 1850s in and around Lourdes, France, when Bernadette first came to the Grotto? What was happening in the Catholic Church at the time? What was the political climate at the time?

- Key players–who was involved in the initial sighting of the Virgin Mary at the Grotto other than Bernadette? Who was Bernadette? What was her background, beliefs, upbringing, etc.? Who were the psychologists and doctors who examined her and others who have since claimed miraculous cures? What is the relationship between key players?

- Location–what other facilities throughout France claimed to offer miraculous cures? What influence did those places, such as the bathes at Eugenie, perhaps have on the belief in cures and the ensuing pilgrimage to Lourdes that continues to this day?

- Religion–how many of the miracles at Lourdes has the Catholic Church officially acknowledge? What distinction do they make between those they acknowledge as “miracles” and the thousands more that they call “cures”? What was the Pope’s response to the Lourdes miracles and how did the Pope use the miracles at Lourdes to strengthen Catholic faith (or did he)?

Other notes pertain to small sections of photocopied works, brochures, tourism pamphlets and information and so forth. Wallace takes note of an interview with Bernadette later in her life. He also obtains an English translation of an interview with Alessandro Maria Gottardi, Archbishop by Dr. Mangiapan of the Lourdes Medical Office. Wallace begins to distill his notes into smaller sections with notations reminding himself at what point in his novel he wants to bring in the information. Wallace begins to create a list of characters for his novel, some based on real people with extensive knowledge of their backgrounds and the roles they played at the time.

Finally–after much of the manuscript outline has been written, the characters developed, and a time-line set up–Wallace travels to Lourdes. There he walks the same path as Bernadette and takes notes on the look, feel, smell, and sounds of the city. He takes notes on the city’s layout (with maps), where and how buildings are situated in relation to the Grotto. Wallace collects post cards, slide souvenirs, pamphlets, and maps. Wallace hires a tour guide and writes about the young, pretty girl with low heels and bare legs who leads the tour, imagining in her another of his characters in the novel.

The research portion of this novel has taken nearly 10 years, from the mid-1970s to early 1983 when Wallace finally begins to write the novel. His inscription on the original manuscript states that he began writing it “on January 20, 1983, when I wrote the first five pages and finished Friday, May 20, 1983, when I wrote eighteen pages.”

And there it is: All the research that went into writing The Miracle, by Irving Wallace.