Hello everyone! It’s officially my last shift as a CCEPS Fellow, and I can’t believe how fast the time has gone. I really feel like my first day was just a few weeks ago! Regardless, I’m excited to report that the Nag Hammadi collection has come so far from where it was when I first started processing it. It’s extremely close to being available for researchers!

The Secret Life of the Nag Hammadi Texts

Hello everyone! Because I’ve devoted so much time to processing the Nag Hammadi Codices Project, I have – as you might imagine – had ample opportunity to consider the scholarly potential of this collection. Recently, though, I decided that it would be fun/enlightening to take a break from the academic side of things and learn a little more about the popular religious culture that has sprung up around the texts since they were re-discovered in 1945.

Once I started looking for information, I discovered there was a lot to find! One of the most entertaining aspects of what you might call “Nag Hammadi Pop Culture” is the connection some people have argued exists between these gnostic texts and…global alien invasion. The basic gist of these conspiracy theories is that gnostic/Nag Hammadi writings about beings called Archons prove that aliens visited earth. And the alien activity didn’t stop back then, they argue. Even today people are being “invaded by Archons,” and that is why we have so much suffering in the world.

But if you’re finding yourself shaking your head in skepticism, know you’re not alone. Scholars certainly don’t view the Nag Hammadi texts as histories of extraterrestrial activity. Although it is true that the Archons loomed large in the gnostic imagination, it’s not because they had recently landed near the Nile in a spaceship. Rather, they were discussed with frequency because they were important mythological figures in gnostic theology. Different gnostic groups propagated different interpretations of Archon theology, but the general themes were usually the same. Namely, gnostics believed that the Archons were powerful, non-human beings. They had less authority than God/the Ultimate Creator, but they had vastly greater power than human beings. As such, they were often presented in ancient writings as hostile or threatening figures that divided humans from their God.

With this in mind, you can imagine how interesting I find contemporary arguments that the Nag Hammadi library is “factual evidence” that the Archons were alien invaders! While I don’t get on board with this theory, I do think it is a fascinating example of how a group of people very far removed from the culture in which the Nag Hammadi texts were created can come up with a very creative interpretation of them…based on contemporary cultural anxieties and concerns. In scriptural studies, there is a term for this: eisegesis. Specifically, eisegesis means, “the interpretation of a text (as of the Bible) by reading into it one’s own ideas.” The goal for scholars, of course, is to avoid eisegesis and understand how the original record creator’s culture and background shaped his or her perspective and – in turn – the text.

What do you think about this? Had you heard that the Nag Hammadi library was being used by some as “evidence” for supposed extraterrestrial life? Maybe you should come look at our Nag Hammadi collection when we’re done processing it and examine the evidence for yourself!

Life Pre-Photoshop

Hello everyone! This week I’ve continued to work hard on processing the Nag Hammadi Codices Project collection. That is to say, I’ve spent a great deal of time organizing photographs of the Nag Hammadi texts, as well as photocopies of these photographs.

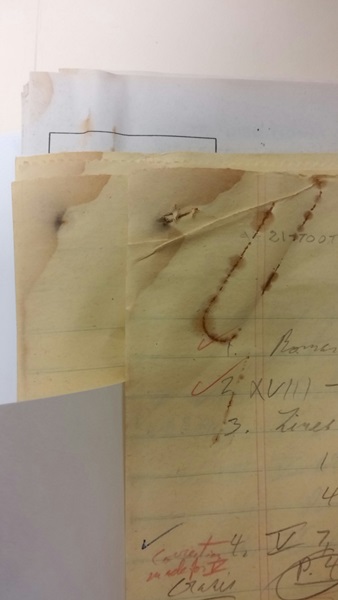

(Disclaimer: I recognize this photo is a little fuzzy, but in order to stay on the right side of copyright law, I need to make sure that none of the text in the image is identifiable! Still, it’s clear enough to provide an interesting example.) If you examine this image closely, you can see multiple layers of images that have been cut out and glued, one on top of another. This is what an actual “photoshop” job looked like back then!

(Disclaimer: I recognize this photo is a little fuzzy, but in order to stay on the right side of copyright law, I need to make sure that none of the text in the image is identifiable! Still, it’s clear enough to provide an interesting example.) If you examine this image closely, you can see multiple layers of images that have been cut out and glued, one on top of another. This is what an actual “photoshop” job looked like back then!Reference Requests!

I filled my first reference request today! A professor at one of the Claremont Colleges is doing research that involves the Nag Hammadi texts, and of course that means she’s interested in what we’re processing over here at Special Collections.

I had the pleasure of meeting her briefly on Wednesday, and followed up on her request to learn more about how she could view the facsimile images of this amazing gnostic library. Although the collection I’m processing won’t be open for scholarly research until I’m done organizing and conserving it, I was able to point her in the direction of some resources that might be helpful for her work in the meantime. I thought I’d share them with you all today, so that any other Nag Hammadi fans out there could settle in for some great weekend reading! There are three main areas I’d recommend looking:

- Special Collections has already digitized many of the Nag Hammadi images, and anyone with an internet connection is free to study them!

- You can find publication details if you’re interested in purchasing (or finding at your local library!) the official, 15-volume facsimile set.

- Not fluent in ancient Coptic yet? No problem! There are at least three scholarly translations of the Nag Hammadi library into English of which I am aware by Bentley Layton, another by Claremont’s own James M. Robinson and the last by Marvin Meyer and Elaine Pagels.

These should be enough to get you off to a strong start! If I find anything else, I’ll let you know!

Scope and Content Notes

This week I’ve continued to work on processing the amazing photographs and documents contained in our Nag Hammadi collection! In addition, I’ve completed a bit more work on the Dead Sea Scrolls files. Specifically, I have created something called “scope and content” notes for each series and subseries in the collection. In this week’s blog post, I thought it might be helpful for me to explain the purpose of these notes, and also to introduce everyone to the closely related concept of a “finding aid.”

UNESCO

This week I’ve continued my efforts to arrange and preserve Special Collection’s many photographs of the Nag Hammadi texts. In doing so, I’ve begun to think a lot about the role the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) plays in helping preserve antiquities. This institution was critically important in helping Claremont’s own Dr. James M. Robinson publish a facsimile edition of the Nag Hammadi trove approximately 40 years ago.

What might motivate UNESCO to engage in this endeavor? Interestingly, UNESCO sees protecting pieces of cultural heritage as a form of peace building. As its website explains, “In today’s interconnected world, culture’s power to transform societies is clear. Its diverse manifestations – from our cherished historic monuments and museums to traditional practices and contemporary art forms – enrich our everyday lives in countless ways. Heritage constitutes a source of identity and cohesion for communities disrupted by bewildering change and economic instability. Creativity contributes to building open, inclusive and pluralistic societies. Both heritage and creativity lay the foundations for vibrant, innovative and prosperous knowledge societies.”

With this in mind, I’ve been wondering how all these precious Nag Hammadi images might prove a unique source of creative inspiration and spiritual guidance in a world that is very different than the one in which these records were originally created. I am fascinated by the ways in which ancient scriptures and philosophies are used, revised, and re-purposed in light of each generation’s changing/historic needs. I hope over the next few weeks I’ll be able to find and share some examples of how people – both inside and outside the scholarly community – have found new and unique meaning in the Nag Hammadi texts!

On that note, I’ll sign off by pointing you in the direction of a really neat document I found this afternoon: a copy of UNESCO’s magazine, The Courier, from May 1971. Check out the article Dr. Robinson wrote on the Nag Hammadi findings inside!

Archivist, meet your new best friend: Mylar

Hello everyone! I’ve finished up another productive few days as a CCEPS Fellow here in Special Collections, and I’m excited to have accomplished so much.

Most of my time this week has been devoted to arranging and preserving the Nag Hammadi Codices Project records. Of the 14 boxes which comprise this collection, 10 of them are almost exclusively facsimile photographs of the Nag Hammadi manuscripts. Although we always make sure to carefully preserve everything Special Collections accessions, it’s doubly important that these Nag Hammadi images are kept in as pristine a condition as possible.

This is because the Nag Hammadi manuscripts themselves are losing more and more of their legibility with every passing year; it turns out being many centuries old will do that to reading material! Given these circumstances, the best way to make sure the information written on the Nag Hammadi papyri is passed down to future generations is to make sure facsimile image collections – such as the one I’m working on right now – are meticulously preserved.

My best friend in this endeavor is a shiny little substance called mylar. Mylar is a clear, acid-free polyester. It won’t ever yellow, and when it is used to encase photographs, it is a powerful tool to prevent image deterioration. As you can see in the below photograph, mylar sleeves come in a variety of sizes:

If you’re having trouble finding a sleeve which is the right size, you can also cut your own – I’ve definitely done that this week!

Although it takes extra time and effort to place every individual photograph in its own mylar case, any archivist will tell you it’s 100% worth it. If you’re interested in preserving some hard copy images at home – especially really important ones (e.g. old family photos of your great-grandparents!) – do consider investing in some mylar of your own! It’s much less expensive than losing an irreplaceable image!

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure!

I am happy to announce that I have begun processing a new, 14 box collection: the Nag Hammadi Codices Project (NHCP) files. That is basically a fancy way of saying that Special Collections has accessioned an amazing group of documents and images, most of which are related to the publication of the Nag Hammadi gnostic text library.

Archivist Toolkit

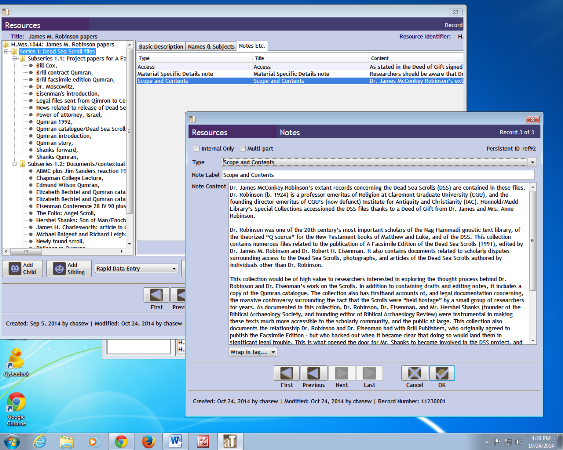

Hello everyone! I am happy to report that my efforts to process Special Collections’ Dead Sea Scroll files are going very well. I accomplished a lot this week, especially in terms of creating records for this series in a program called Archivist Toolkit (AT).

AT is an open source data management tool. As the AT website explains, it was developed by the “University of California San Diego Libraries, the New York University Libraries and the Five Colleges, Inc. Libraries, and is generously funded by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation”

So you can get a sense of what using AT is like, I’ve included some screenshots here. The first thing I do when opening the program is go to the “Resources” section. There, I find the collection where the Dead Sea Scroll files “live;” in this case, that means I go to the James M. Robinson Collection.

A little historical background is useful here in understanding why we organize things this way. As you may know, Dr. Robinson is Professor Emeritus in Claremont Graduate University’s Department of Religion. With Dr. Robert Eisenman (Cal State Long Beach), he helped publish A Facsimile Edition of the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1991. The publication of this book, along with the Huntington Library’s decision to make thousands of photographic negatives of the Scrolls available to researchers, made these texts available to the entire scholarly community for the first time. Prior to these events, access to the Scrolls was controlled for decades by a small in-group of scholars who kept these ancient documents to themselves. The twists and turns of this story, as well as the involvement of Dr. Robinson and Dr. Eisenman in breaking this “scholarly monopoly,” make a fascinating tale. I highly recommend you explore their work – and maybe even read through Special Collection’s series of Dead Sea Scroll files when they’re ready! They contain all sorts of intriguing details about what Dr. Robinson and his colleagues had to go through in order to publish these texts.

All of this is to say: when Dr. Robinson retired, he graciously donated his personal papers – including the Dead Sea Scroll files – to Special Collections, so that the scholarly community could continue to be enriched by his work. This is why you’ll see that I go to the “James M. Robinson” collection in AT when I want to work on digitally organizing the Dead Sea Scroll series:

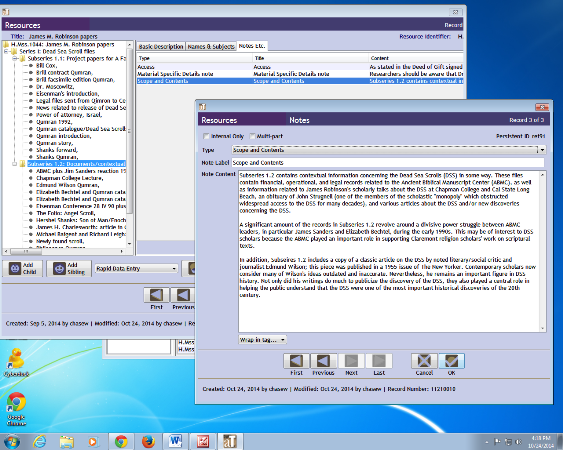

Once I’m inside the series, I organize it on the subseries and folder levels. I can also add notes to help researchers get a sense of what’s inside a particular file. For example, in “Subseries 1.1: Project papers for A Facsimile Edition of the Dead Sea Scrolls (1991), edited by Dr. Robert H. Eisenman and Dr. James M. Robinson,” I have a folder entitled, “News related to release of Dead Sea Scrolls.” And inside of that record, I have a further record – a note which explains that this file:

Contains both popular and serious news articles related to the publication of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Also includes information related to political conditions during the time period surrounding their release, and a copy of the Society for Biblical Literature’s ‘Statement on Access’ to ancient materials.

When I’m working to describe the collection on a folder level, the AT screen often looks something like this:

To sum up, AT is a great piece of archival technology, and I’m happy I’m getting the opportunity to learn how to use it – especially since it will make it so much easier for researchers to find what they need in the Dead Sea Scroll files once I’m done recording everything! If you’re interested in learning more about this program, or downloading a copy of AT for personal or institutional use, I encourage you to go to the AT website. And if that’s not enough to quench your archival curiosity, you can even follow AT on Twitter.

The Week of Fantastic Photocopying!

I’ve enjoyed another fascinating week here as a CCEPS Fellow! This week I finished arranging Honnold/Mudd Special Collections’ Dead Sea Scrolls files. During this process, I spent the majority of my time carefully going through each file and putting everything in chronological order.

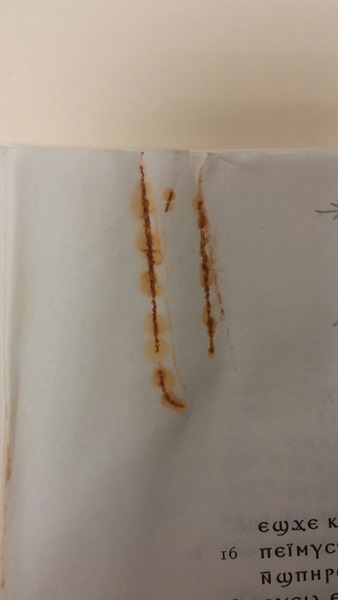

After concluding this process, I attended to the necessity of photocopying all fragile documents on acid-free paper. After making these xeroxes, I discarded the original records – which were falling apart! This allowed me to rescue content without keeping a crumbling document in the collection – one which could very well end up illegible down the road, and perhaps even damage other documents as it decayed. To illustrate: I recently encountered a decrepit newspaper clipping which seemed intent on self-destruction – and had already stained the record next to it a nasty yellow! Fortunately, we had an unharmed duplicate of the stained document, so no long-term harm was done. However, this is a good example of what can happen when cheap paper products are allowed to sit for years on end, unpreserved.

Among the materials in this collection that necessitated photocopying were any periodicals printed on inexpensive paper (particularly newsprint), carbon paper, carbonless copy paper, and thermal paper. This last item was commonly used in earlier fax machine models. As it turns out, Dr. James M. Robinson – who donated the Dead Sea Scrolls collection to us – communicated extensively by fax. This meant there was a plethora of thermal paper to be dealt with over the last week! I’m so glad Special Collections received these documents when it did, because records printed on thermal paper can fade rapidly with time, handling, and exposure to light – and the ones in this collection were doing so. Thermal paper is a highly unstable medium.

In case you’re hankering for a look, here’s an image of the oh-so-hardy photocopier on which I made many dozens of xeroxes for this collection:

And here’s Special Collections’ well-stocked, acid-free paper bank – a corner I came to know well while I worked!

As I hope you’ve seen this week, the world of archival preservation and paper chemistry is really pretty fascinating. If you’re interested in reading more, I recommend you check out Michigan State University Libraries’ piece on de-acidification. Australia’s National Archives also have some clear and helpful guidelines on paper preservation as well.