Research has been going well. More and more materials are finding their way into my already large horde of 17th century science literature. Navigating the search engine is not as straightforward as it seems, which means I’m still learning to use the right terms to get me what I want. Nonetheless, I am finding more and more every time I sit down to search through special collections.

Some of the most amusing things I’ve found in going through these materials is the blatant intermixing of myth and science. Early on, I noticed some notions of travel literature and scientific reports being less-than-accurate concerning zoology and even metallurgy.

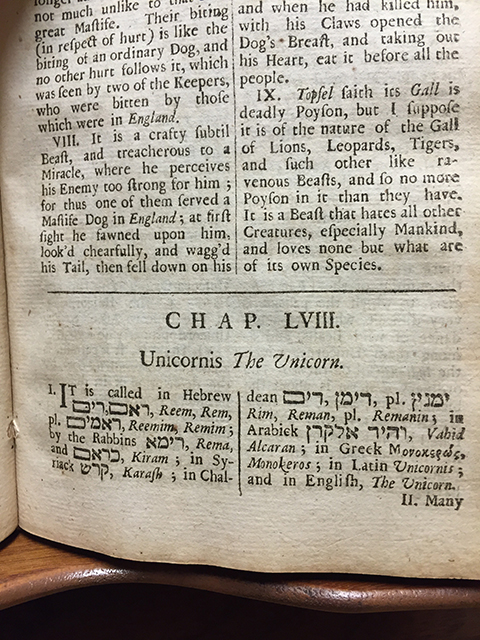

Here, from a collection of The Works of Sir Thomas Brown, is a description of the Unicorn. I particularly enjoyed this encyclopedic section of different animals, plants, minerals, etc. because it gave all the names of the subject in different languages and described their significance in different parts of the world.

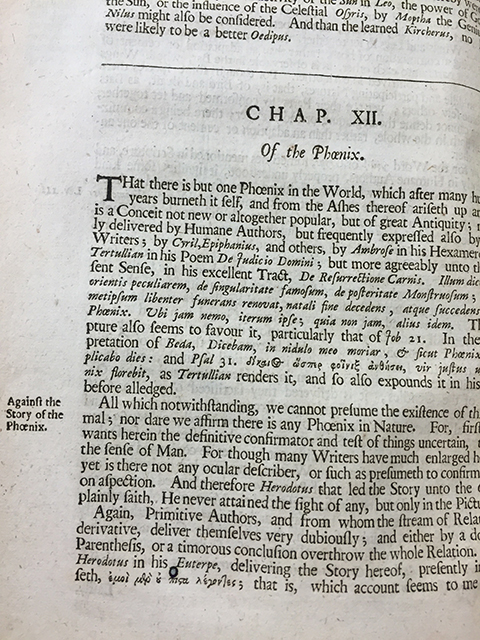

From that same work is a description of the Phoenix. Sir Thomas Brown also included the literary significance of some of these creatures, when applicable.

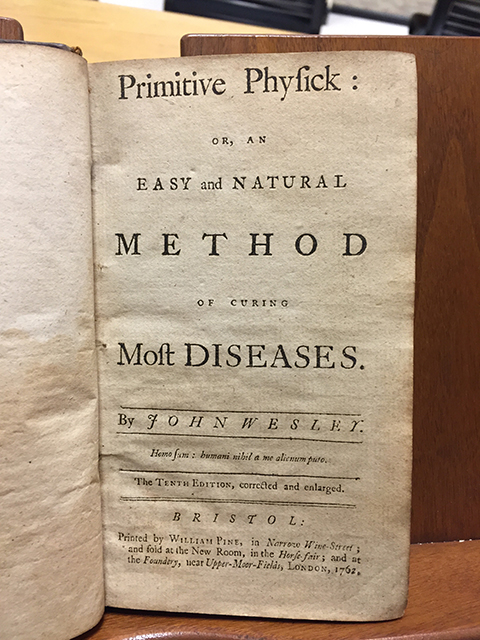

One book that piqued my interest was Primitive Physick by John Wesley. For such a medically-inclined book to be written by this well-known theologian and philosopher was surprising to me and I quickly starting finding secondary sources to help me learn more about it. It’s fascinating what Wesley was doing, because in this early modern era when the spiritual and the physical were bingeing to diverge, he argued that they were still very related. Half of the work served as a space for this sort of argument, and the rest followed the tradition of medical receipts.

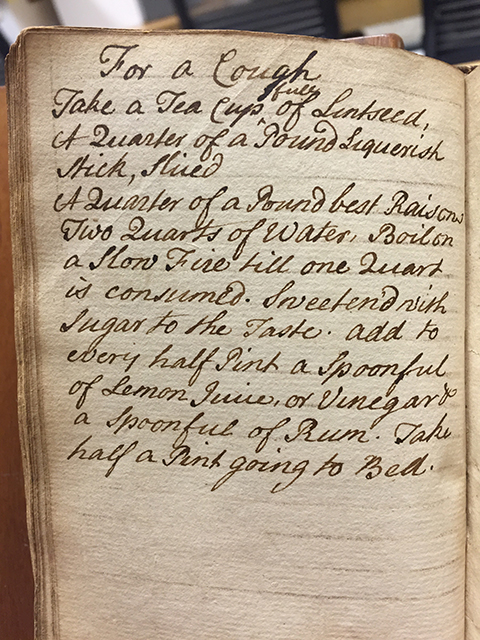

Within this edition, there also existed some marginalia from an unknown source. The notes were mostly additions to the prescriptions and medical instructions.

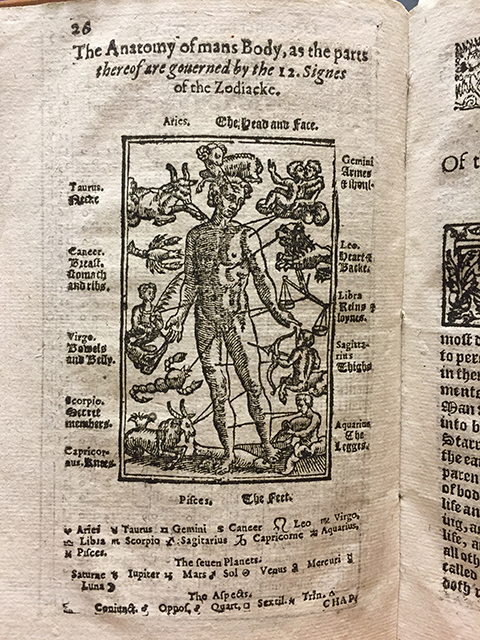

As I continue on, it is very clear that this period was one of ambiguity when it came to where to draw the line between the medieval and the modern. In my next blog, I will share more about my work with The Anatomy of Melancholy. But this illustration from A Concordance of Years shows that the heavenly and the physical were definitely seen as intertwined, or at least that man’s body was governed by elements outside of himself.