For me, the bear is Senior Year and the impending task of entering adulthood. It’s fierce and ambiguous, just like in The Winter’s Tale, but unlike the poor soul devoured by Shakespeare’s brainchild, I plan to fight and conquer it.

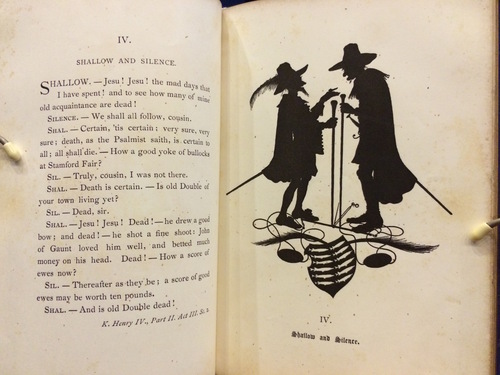

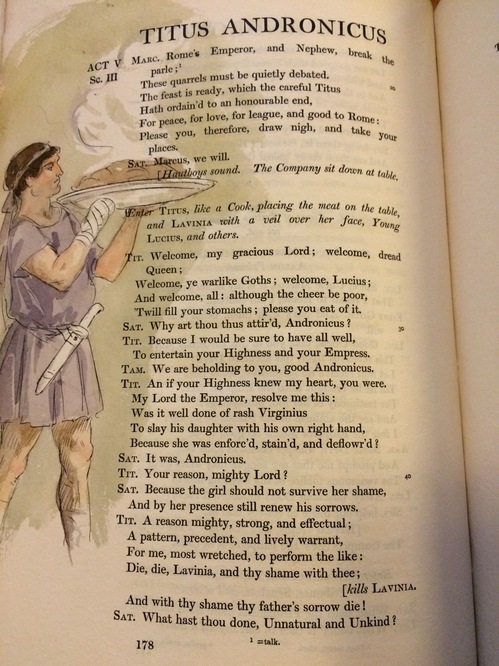

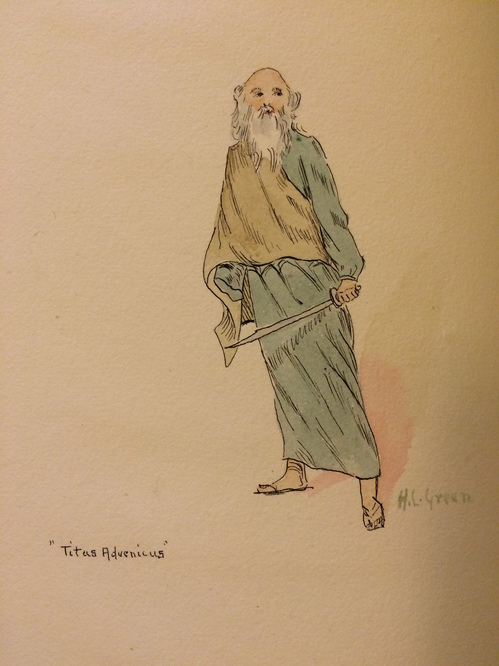

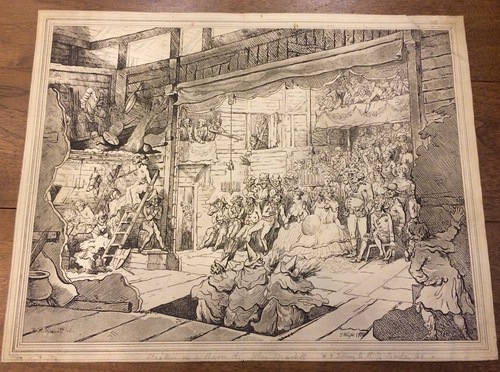

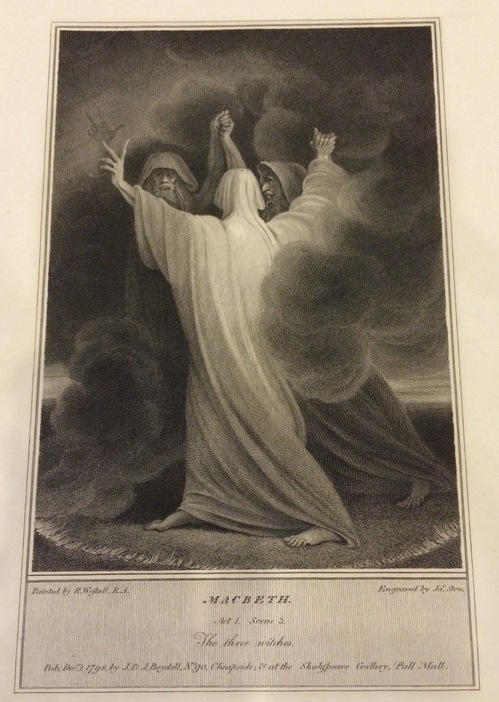

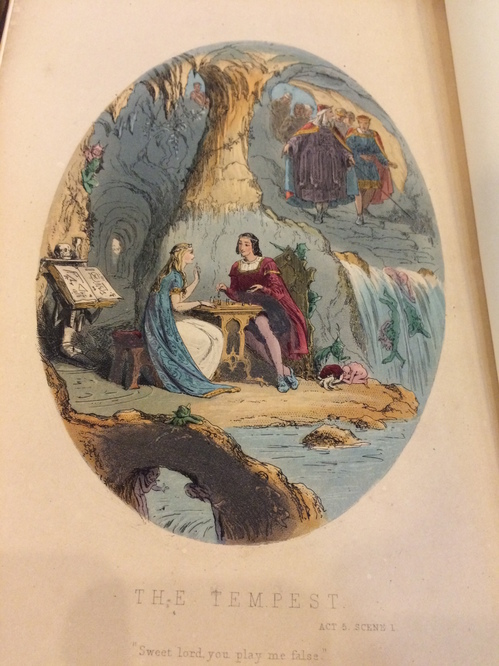

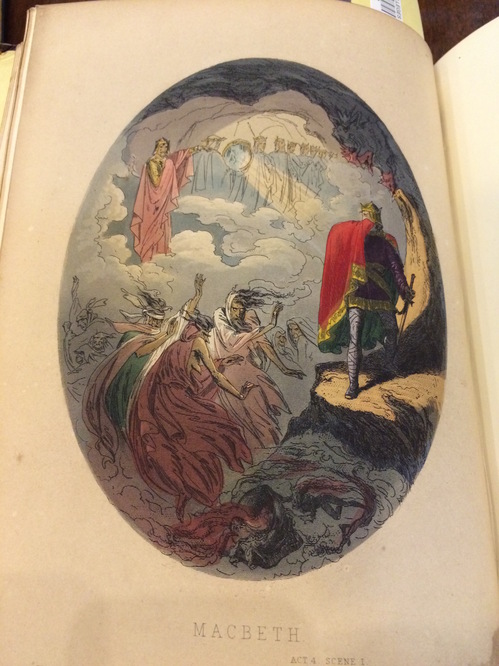

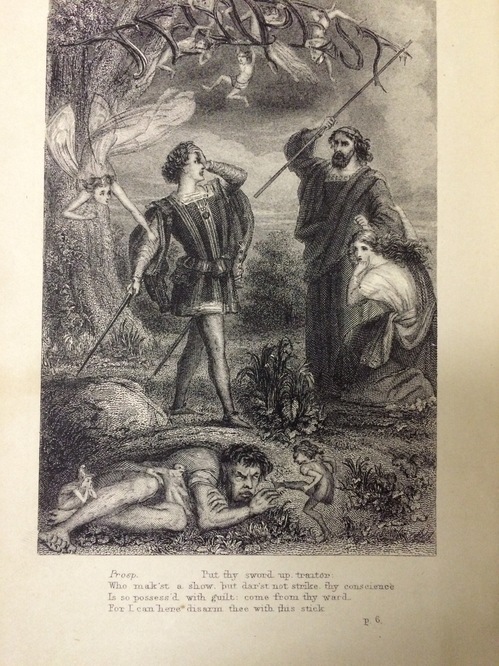

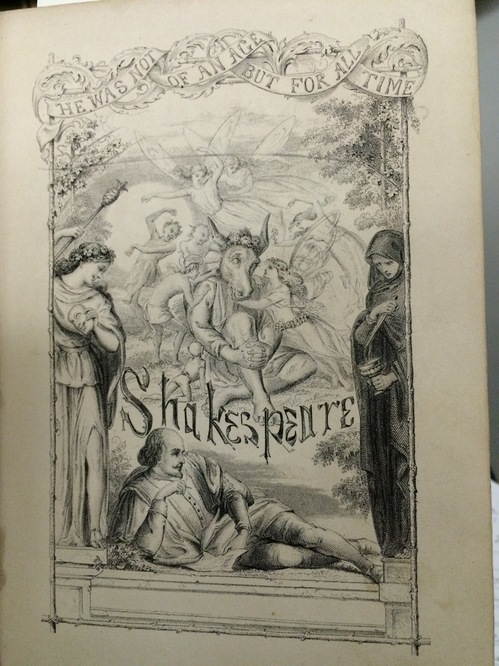

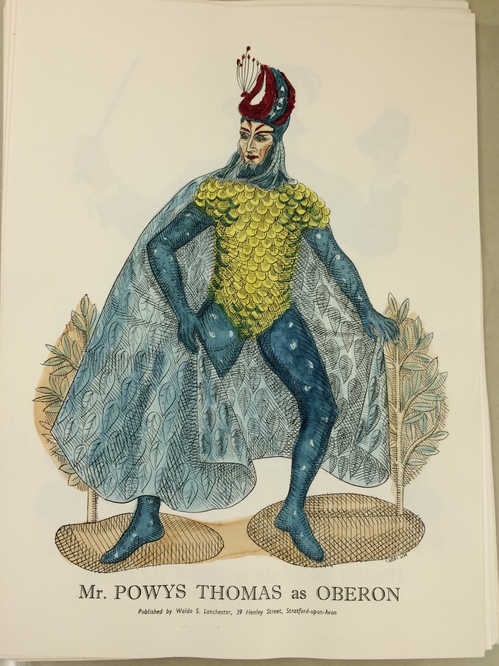

In other words, my time as a SURP-CCEP researcher has come to an end. And, continuing the trend of Emma’s last post, I’ll be reflecting on my summer researching Shakespeareana. Before I get into that, here are a few cool drawings from the Philbrick art collection of actors as their characters.

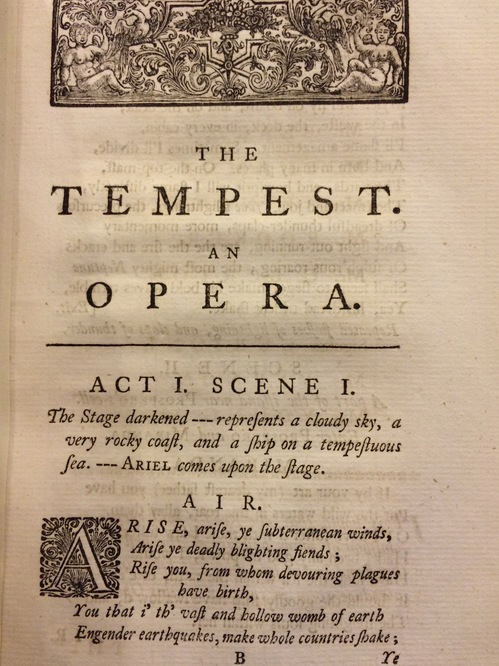

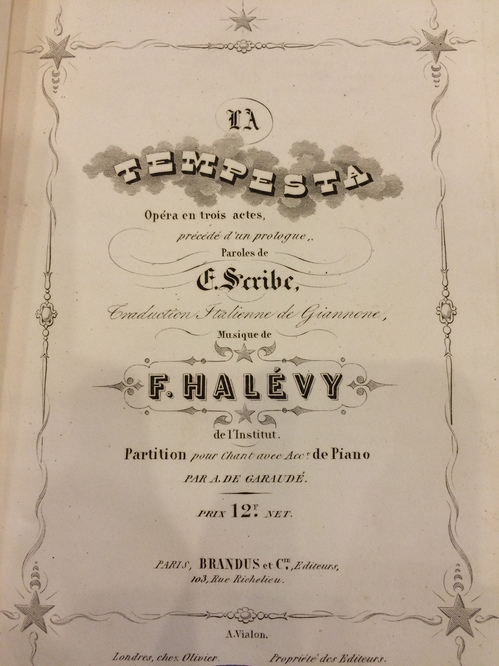

This summer, my fellow researchers and I came across many items that took Shakespeare and altered it to suit their needs. Some people took out anything they thought was inappropriate for families (which takes out a lot of the fun, honestly), some made tragedies into comedies, and some made the plays into short stories for children. To me, this points to a level of audience participation, or, an extension of the co-authorship of plays at that time, since fans of Shakespeare’s work would remake the plays in an experimentation of form. They were putting their own spin on Shakespeare, which as I have found working with multiple versions of the same play, opens up new readings of both the inspired and the original works.

Seeing these kinds of interpretations and alterations to Shakespeare’s plays shows me that Shakespeare is bigger than himself. By that, I mean he is not only a cultural icon, but he is also a genre in and of itself. He uses tropes that others reproduce in order to imitate his style. He has characters that he reuses. He even has overlapping and repeating plot points and structures. And even today, we tap into those structures that Shakespeare set in place, furthering and reinforcing the definitions of his self-perpetuating genre.

I’ve thoroughly enjoyed my work this summer, and I hope you’ve enjoyed reading my posts. Even if you don’t feel compelled to go out and read anything by the Bard, hopefully you’ll look at him in a new light.

Thank you for being my readers.

Until the Spring,

Alana