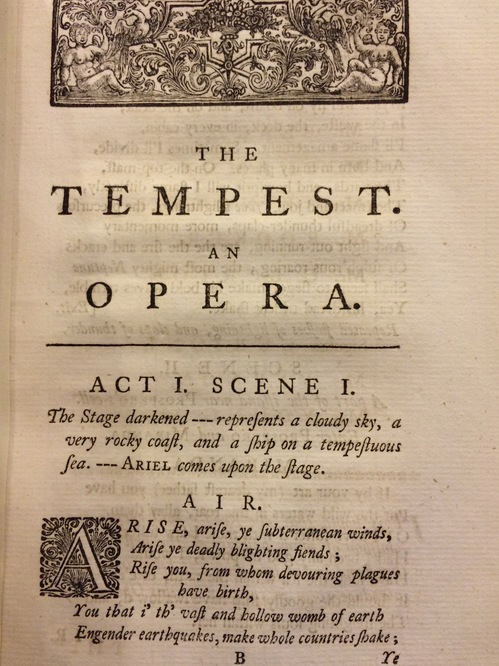

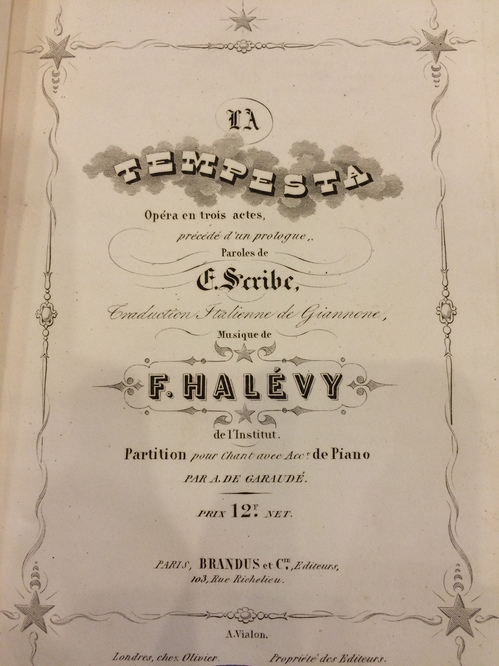

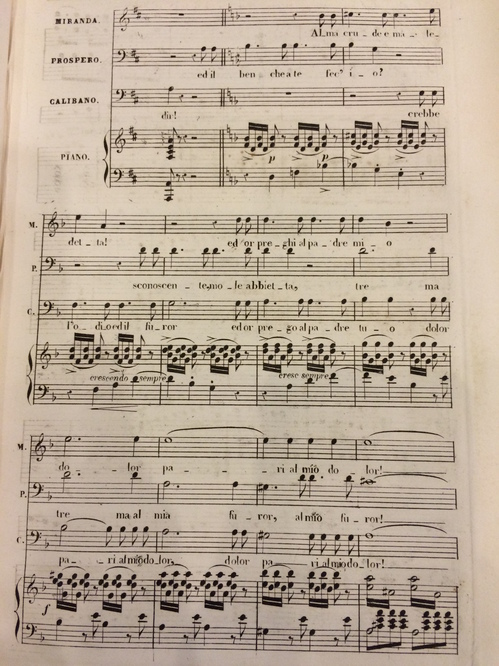

This week, in preparation for our exhibit, I’ve been thinking more about versions. More specifically, different versions of the same thing. So today, I’ll be talking about four different versions of The Tempest. I found some pretty cool stuff in the Honnold special collections, as well as in the collection at Denison Library (Scripps College). Not only did I see beautifully illustrated editions with the unaltered text, but I even found two operas.

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:”Times New Roman”;}

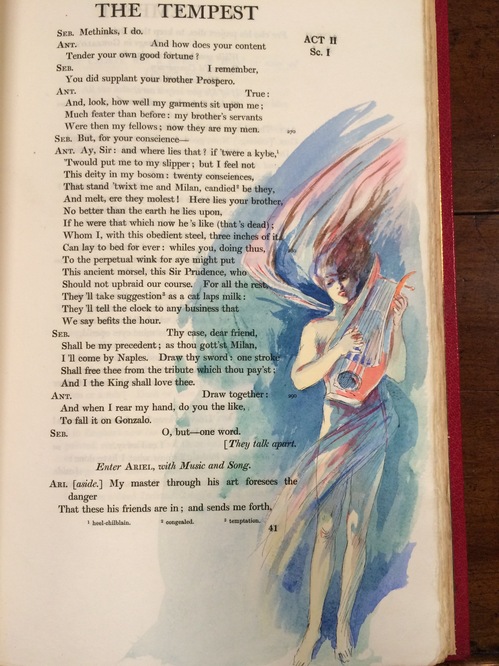

In the vein of co-creative influence

and difference, I want to quickly talk about two illustrated editions and the

illustrator’s choices (which impact a reader’s interpretation). The first book

contains watercolor illustrations, creating a softer overall image. The second

takes a more whimsical, almost sinister or mischievous approach.

In this first edition, Ariel is more

human than magic. He could be a fairy or an ordinary man based on his

appearance.

In contrast, the second edition

portrays his as more spritely, with more pointed features, as well as more

magical characteristics.

We see Ariel as a formless force,

clearly a magical being, but also with the suggestion that he himself is

elemental, is the wind.

These two different sets of

illustrations further point to the versatility of interpretation in The Tempest (as well as many of

Shakespeare’s other works). In each one, we see an artistic twist, but in each

we can see the core of the source, Shakespeare’s magical tale of an abandoned

island where music is in the wind and creatures lurk just out of sight.