I’ve been thinking and reading a lot about court masques this week, specifically about the style Ben Jonson worked to form. For those of you who don’t know, court masques were theatrical productions for British nobles containing music, dance, songs, and poetry in varying degrees. In addition to the dancing, performance, and revels, they included elaborate set designs and special effects.

Now, I know Jonson isn’t Shakespeare, but they were contemporaries, and in many ways, the masques were like plays of the time. Though the two inhabited different spheres, private versus public, and dealt with different notions of fiction and reality within the space of the performance, both may be read as literature. By that, I mean that the play remained isolated, whereas the masque could blur the line between fiction and reality because many times, nobles themselves would act in the performances.

Other times, the masquers would dance with members of the audience, uniting the actors and observers in an in-between space of active entertainment. Such an amalgamation between fictional characters and real life persons sets the tone for further combinations of different realities.

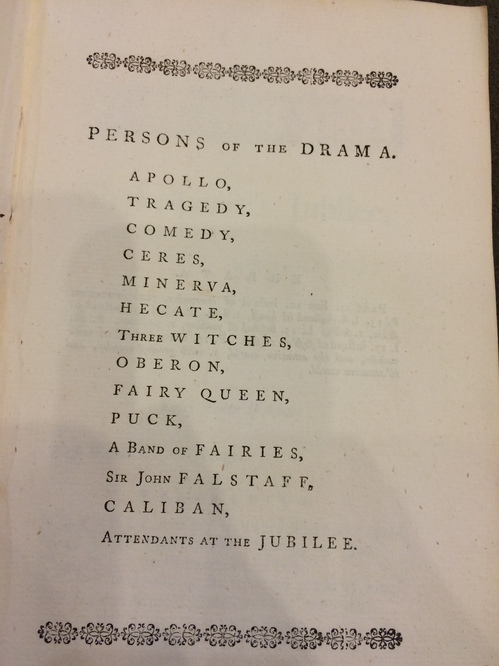

Why, you ask, have I been looking at something that is definitively not Shakespeare? Well, it’s because I’ve been finding several items in the Special Collections that fall into the category of masque using Shakespeare’s plots and/or characters. And on the note of combining different realities, one in particular performs a sort of literary mash-up or crossover, making characters from Macbeth and Henry IV interact with Greek Gods, such as Apollo and Minerva, and even muses, like Comedy and Tragedy.

Not only does this masque mix the different worlds of Shakespeare’s plays, it also combines them with classical mythology. Not only does this fall into the masque tradition of using Classical figures to augment the performance, but it sets up Shakespeare as worthy of such comparison. In a way, the masque suggests that Shakespeare’s characters are as powerful and everlasting as the Greco-Roman gods.

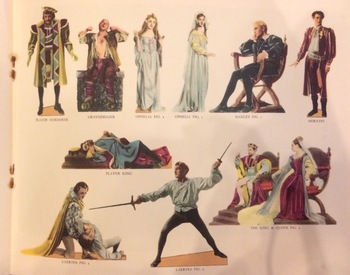

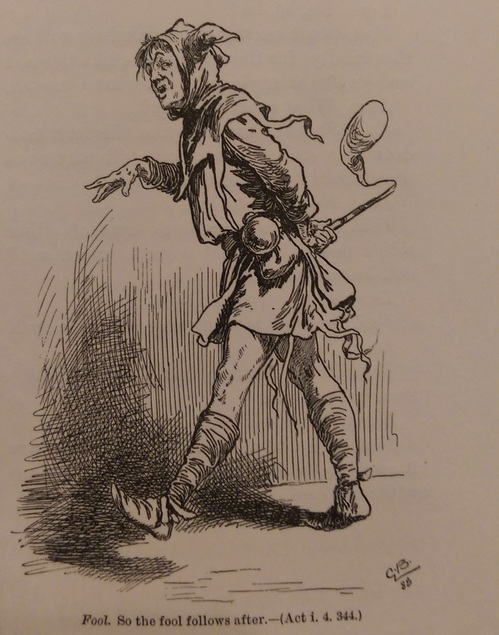

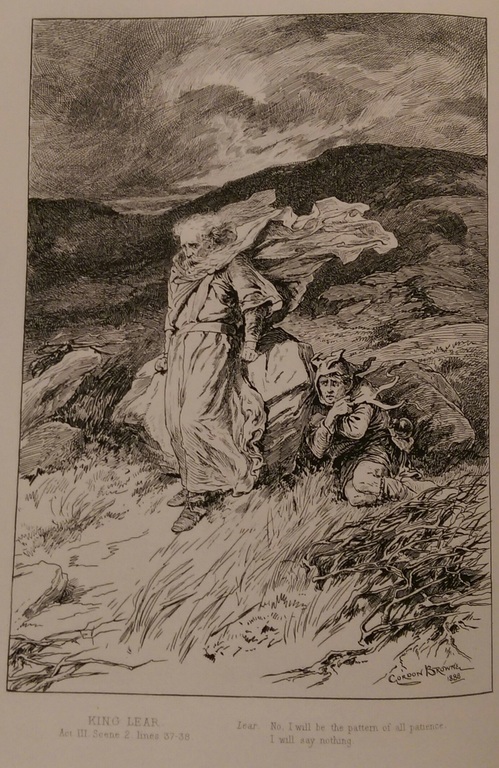

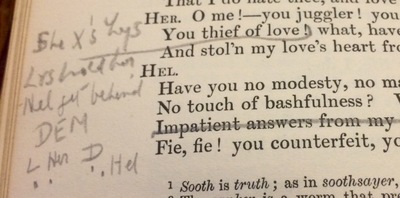

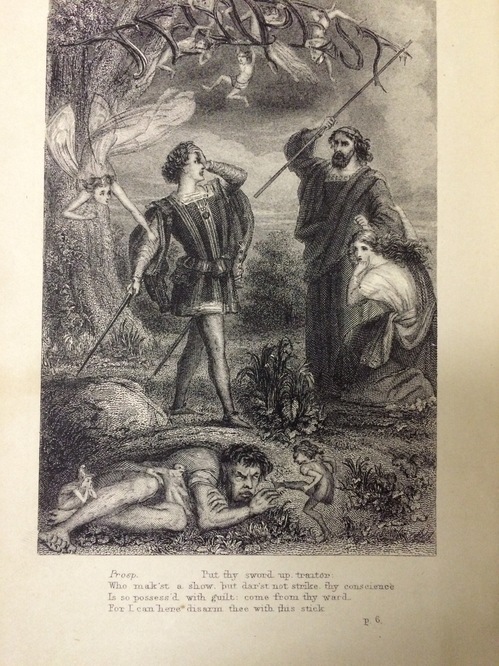

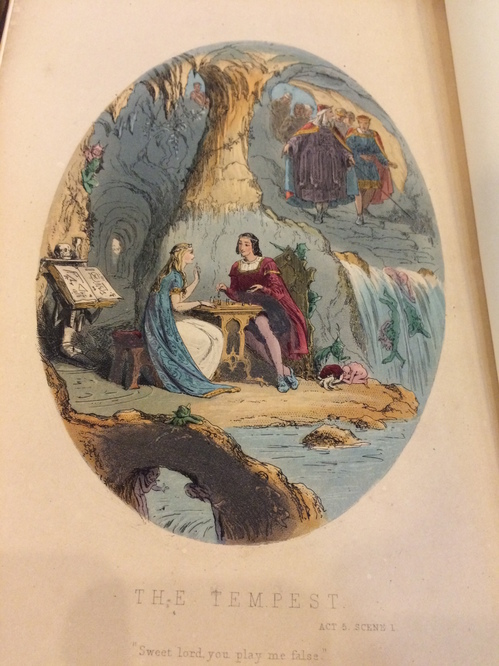

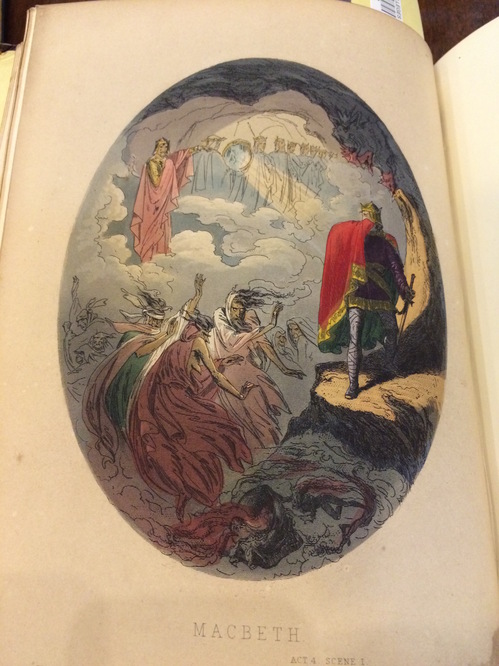

The court masque, in a way, lives on through printed editions of Shakespeare’s plays by drawing on the concepts of spectacle, design, and illustration as accompaniments to the text of a performance. A few examples show colorful scenes from The Tempest and Macbeth.

Both place the characters in a fictional world, choosing instead to make the scenes they depict works of literature rather than theatre. Through these pieces (including the masques), we see a form of genre manipulation taking place, showing the versatility of Shakespeare’s works.

That’s just another reason to appreciate Shakespeare. And for further genre manipulation, watch The Lion King (a version of Hamlet), or even take a gander at a graphic novel based on the Bard and his characters called, Kill Shakespeare.