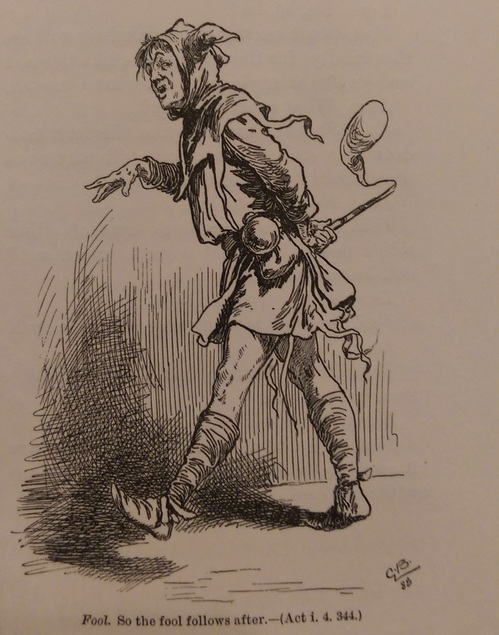

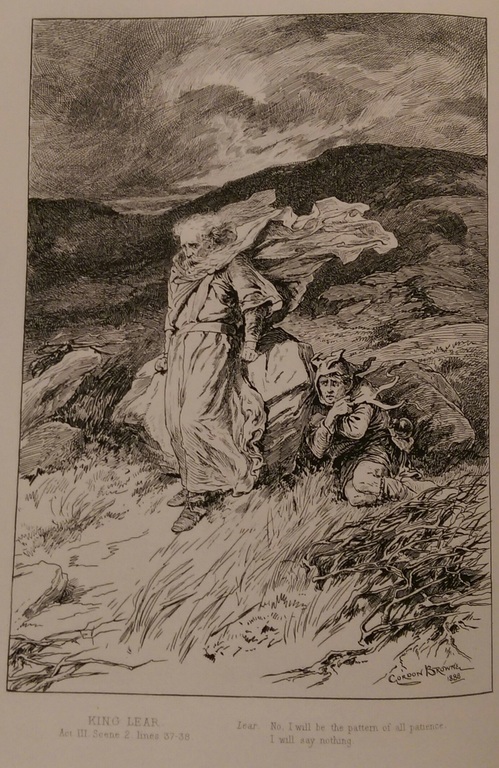

I’ve spent a good chunk of my time with King Lear pondering (or maybe just being weirded out by) the king’s Fool. I’m not the first reader to feel the Fool is a bit off. Nahum Tate’s infamous “happy ending” Lear left the character out entirely. The Irving Shakespeare, the same series from which I posted images when I wrote on Measure for Measure, tells us that the Fool was nearly kept out of the revival of Shakespeare’s original plot in 1836. Illustrations of the Fool from that edition, housed in Special Collections, are below:

The Fool is often described as a prophetic voice, one that speaks for the play to the audience. I think this plays into what makes the Fool unsettling, at least for myself: the Fool functions in a variety of ways on stage, but it is difficult to ascribe him personal motives at all (whereas other characters certainly have some motive, disputable though it may be). And it isn’t clear that the Fool has emotional responses to what takes place on stage, instead simply providing commentary.

The Arden Shakespeare’s introductory comments on the Fool, for example, characterize the Fool as “shrewd, witty, and very much a conscious entertainer.” These are, on the one hand, descriptive of a human personality; on the other hand, they do not indicate at all what the Fool cares about, and the Arden commentary does nothing to attempt to answer this. A more emotive description says he “breaks out of every category in which might be fixed. Young or old, humble or aggressive, sad or merry, sensitive or acerbic, most representations of the Fool tend to emphasize his strangeness, his difference from others…

The “difference” between the Fool and the other characters is that the Fool is performing–not merely is he played by an actor, but he is of course an actor, and his job is to play a part while the other characters go about their “real” lives. What disturbs me, then, is that we never see him break character. But I use “see” in the sense of the reader, and perhaps the Fool on stage is a different experience–can he really be played as constantly in jest? The above illustration shows a Fool fearful of the looming storm, perhaps suggesting the answer is no.

Is the Fool really “strange” then? It’s difficult to say. Since he’s always acting, we never know how he really acts on his own time. His behavior is strange in the sense that, as Cavell discusses so enjoyably, theater is rather strange behavior. To make an analogy of it, someone might observe and find us to be creatures with emotional depth. But when we went to the theater, that person might wonder why the actors on stage created such an unsettling effect, why they were producing such strange and inaccessible renditions of our own behavior. So it is with us and the Fool; we come to expect a certain kind of theatrical model in which characters, particularly in tragedies, have clear desires and schemes. When one character simply wants to play-act and editorialize, we feel strange indeed.