That’s right, my SURP is over. I am now out of Claremont to hang out with my family (and then come back to do my junior year of college – oy).

Ruff and Tumble

Try as I might, I can never seem to internalize the fact that people in Shakespeare’s time really wore the tights and ruffs and doublets as fashion. I can’t picture anyone choosing to wear that unless it was a joke, or a costume party, although that is probably just an effect of the fact that I’m commenting on these fashions ~450 years in the future (I guess skinny jeans are sort of like the modern version of Elizabethan hose so I really can’t talk), but regardless, I can’t see those outfits without interpreting them as a throwback to Shakespeare rather than a representation of the world at that time – Shakespeare is likely the most culturally significant person from that time, but all over the world people dressed somewhat similarly, and seeing a whole style of dress as a reference to a playwright whose work is often not performed in Elizabethan dress ignores the trend of fashion all over Europe.

For your viewing pleasure today I have a few images of French nobility dressed as they would have been in the late 1500s. Side note: the sassy hand gestures in most portraits of people from the past consistently give me happiness.

These pictures have some elements that remind me of the French period dramas I love so much: the socks with the tie at the top, the fan that Lady In Pink carries. The rest of the clothing – the wide skirts, the almost ludicrously large ruffs, the doublets, and yes, the hose – are all staples of Elizabethan fashion. As it turns out, ruffs were clothes for both the nobility and the lower classes – after the addition of starch, they could be worn over and over again, and thus became popular for many classes of people. These outfits were normal for everyone.

These pictures have some elements that remind me of the French period dramas I love so much: the socks with the tie at the top, the fan that Lady In Pink carries. The rest of the clothing – the wide skirts, the almost ludicrously large ruffs, the doublets, and yes, the hose – are all staples of Elizabethan fashion. As it turns out, ruffs were clothes for both the nobility and the lower classes – after the addition of starch, they could be worn over and over again, and thus became popular for many classes of people. These outfits were normal for everyone.

More interesting to me (besides reminiscing about historical fashion in movies) is my reaction to seeing people in these clothes. As I mentioned, my first thought upon seeing these, and likely the first thought for many other people, is, “Whoa. Shakespeare throwback.” History tends to crystallize into the greatest hits of a century or a decade or what have you; Elizabethan times are Shakespeare and the plague and ruffs, for me. My focus on Shakespeare makes me wonder what other history and life I’m unaware of; of course, Shakespeare is the most talented playwright of that time, but just because J.K. Rowling is the most successful young adult fiction writer of our time doesn’t mean that everything else in that genre is worthless.

In terms of this SURP, my time is almost up; I have one more week (and one more blog post!) to go. If you’ve liked the sort of analysis my co-researchers and I have been putting forward, come see the exhibit in Spring 2016, and come talk to us at the poster conference this September 3!

Now, a Joke: Richard III, Othello, and Shylock Walk into a Bar…

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:10.0pt;

font-family:Cambria;}

Here

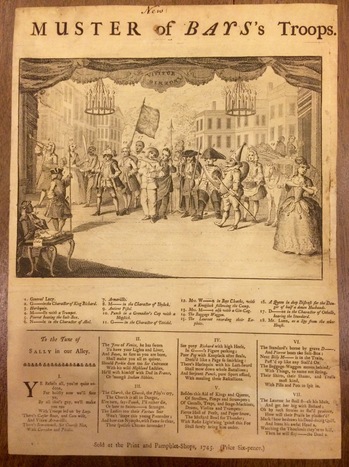

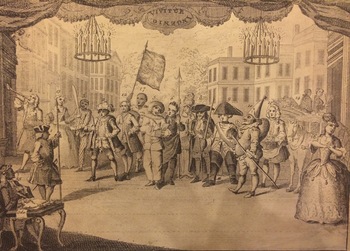

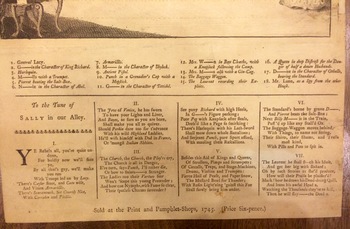

we have “The Muster of Bays’s Troops,” what appears to be a satirical cartoon featuring

many fictional characters getting ready to fight a war by singing a little ditty.

Most of these characters are unfamiliar or insignificant in terms of

Shakespeare (although it is fun to see Punch of Punch and Judy in there), but

scattered around the battlefield we see King Richard (#2), Shylock from Merchant of Venice (#8), and Othello

from the play of the same name (#17, holding the flag in the middle).

These

three Shakespearean characters span the range of Shakespeare’s works; Richard

(I believe he is Richard III but I

can’t really tell) is from a history, Othello a tragedy, and Shylock a comedy. Unfortunately,

as I am not yet an expert on mid-18th century humor, and because the

internet was mostly unhelpful, I can’t tell you why these three characters

specifically made the cut, or even what this piece satirizes…Bibliotheca histrionica, a catalogue of the

theatrical and miscellaneous library of Mr. John Field which will be sold by

auction -the catchiest of titles- briefly mentions this image as a “satirical on Garrick and Lacy, with verses.”

David Garrick was a widely celebrated actor, well known for his performances of

Shakespeare. In the cast list of this image, King Richard is specified as the

performance of “G—–,” which I am interpreting as a reference to Garrick.

In

the song attached to this piece, characters are often referred to not as the character,

but as the actor who portrays them, which places the reader at a distance from

the characters and emphasizes the strong relationship that often arose between

actor and character. It also seems to suggest that the character no longer

matters; Garrick could be playing anyone at all and still have his spot in the

image. Character is secondary to actor.

In

this song, each character is mentioned briefly as part of the army that will

overwhelm the rebels. Part of the joke, I think, is that these men are mostly

unassuming/unimpressive… The viewer should “See puny Richard with high Heels, / In G—–‘s

Figure perking…And Serjeant Punch,

pure Sport afford, / With mauling these Rascallions.” Punch is dressed like a

jester, and although known for, well, punching, he is not the commanding physical

or leaderly presence one might expect from a sergeant. Richard here is

emasculated and used as an example of a non-intimidating fighter.

Although

the writer here uses specific details from the plays – Shylock has sworn to “have

your Lights and Liver” – these characters do not seem meant to be faithful

representations of Shakespeare’s characters. They pass out of the realm of

being specific characters in his plays to being convenient archetypes or

examples to carry on a joke. In the Hamlet

burlesque (comedic, irreverent retelling of Hamlet in one act), the preface brings up the people who would be

offended by mistreating the Bard and his characters in such a way, and mentions

that there is no writer better suited to a burlesque. Not to change his plays

and characters in such a way would imply that Shakespeare’s work is not strong

enough on its own to withstand a liberal retelling, that Shakespeare’s

reputation is fragile and can be ruined by a parody. This idea reframes extremely

different productions as not taking away from the brilliance of Shakespeare but

adding to it by showing how recognizable the play is even in something like a

burlesque, and as a symbol of how far Shakespeare inspired the next writer to

go.

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:10.0pt;

font-family:Cambria;}

Shakes-Pierre

Courtship the King Henry V Way

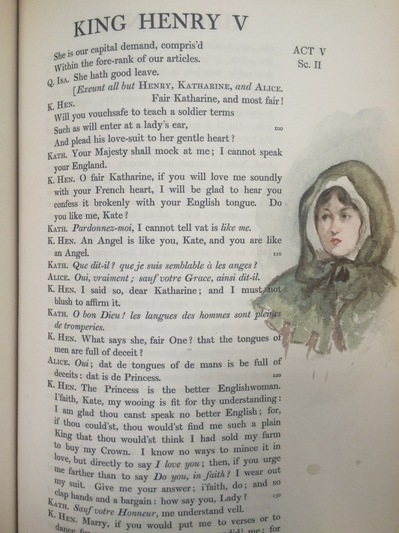

In a Shakespeare class I took last semester, I read a great article by Phyllis Rackin and Jean Howard that explained how Henry V shows the shift of masculinity at the time Shakespeare wrote the play. Before this play, masculinity was linked to nobility through blood, i.e. preservation of a bloodline, whereas Henry V is the first of his plays to show masculinity as a result of achievement or conquest in battle and in love. Lust was once a feminine, emasculating vice, because a woman could dilute the bloodline and thus remove your masculinity, so denying women sex was seen as an expression of dominance. In this play, lust belongs to men as a tool of power; successfully seducing someone shows that same male dominance.

Near the end of Henry V (spoilers ahead!), King Henry seduces the French princess Katherine and marries her, thus sealing his control over France and validating his authority as a man and as a leader. This scene is often seen as a sort of coercion or forced wedding; Katherine barely speaks any English (and barely speaks at all) while Henry does the wooing, marrying her with little preamble and little input from her. It is likely that at different times in history, this scene was more or less romantic and organic; nowadays, with the emphasis on female autonomy that has been growing, this sort of seduction becomes problematic and unromantic, at least as I see it.

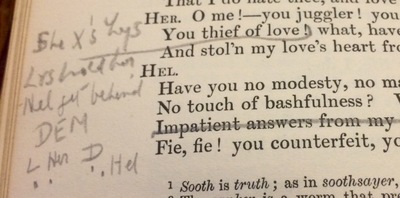

In this picture, drawn by an unnamed reader, Katherine looks very young, swaddled and protected by a large hood. She looks almost sad, unmoved by the “conversation” taking place right next to her face. Maybe this reader thought the seduction was romantic and reciprocated; we can’t know just from looking at this image. But the way that Katherine is shown – her clothes, her face, her expression – all contribute to a narrative about what this seduction means to the seduced party. Going through the scene with this mental image is very different from the next image:

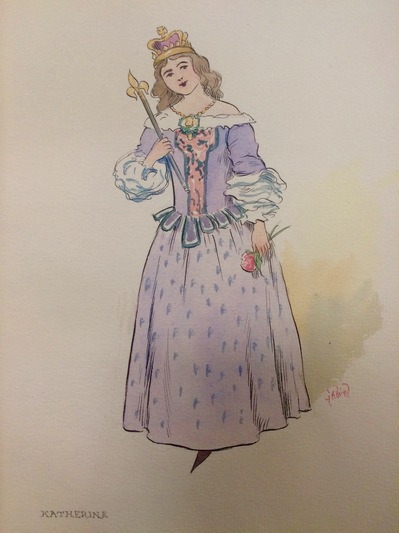

This Katherine, an image from the same copy of the play (by a different artist) shows a classic princess smiling sweetly in her pretty gown. Her royal status is emphasized by the crown and scepter and her romantic side comes through thanks to the flower and the sweet expression on her face, just as King Henry wanted if he is indeed partially using her to validate his authority. This Katherine fits the bill for what one might expect a willing contributor to a royal marriage to look like. If this Katherine comes on stage, the wedding is more likely to be a happy occasion than something done strictly for political gain, or unwillingly.

This photo is, to me, the most interesting. Entitled “The Wooing of Henry V,” here we have Katherine sitting forlornly on a throne, accepting Henry’s grand physical expression of love and desire. This Katherine looks like an adult woman, sitting in a position that normally would be one of power. She is a very different Katherine from the first two I’ve shown you, but at least in this still frame, we still see nothing to suggest that she wants this marriage as much as he does. Even the title gives a sense that this is not a conversation; it is a directed seduction. Henry woos Katherine, an unmoving, possibly undesirous female.

To me, this seduction style is a flaw in the personality of the manly, charming Henry V. But to some, this scene is utterly romantic, an expression of love at first sight and the strength of love even with a significant language barrier. These opposed understandings of the same scene and relationship could reflect shifting cultural values over time, or it could simply be a result of who I am and how I was raised. The beauty of costume, design, and acting is that these elements combined could make me see an entirely different interpretation of the scene; possibly, if a charming Henry wooed the girl in purple from the second photo, I would be more on board with the seduction, at least in that production. The creators of different productions have a lot of power over interpretation, and they have no choice but to use and thus impact my understanding of the play.

Hamlet: A Fellow of Infinite Jest

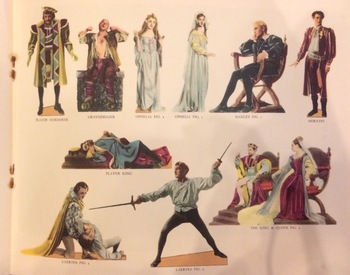

This week’s SpeCol (Special Collections) Scoop comes from the Philbrick Collection, which is a massive collection of drama-related media donated to the school by the Philbrick family. One of these boxes is a collection of sets for toy theaters, which were somewhat like dollhouses with removable backgrounds and paper dolls. From what I can tell, toy theater companies chose short plays, gave plot synopses, usually in one act, provided the backgrounds for each scene, and gave the characters in various necessary positions for the play.

The Unscripted Kiss

Queen Mab Intervenes/How Much Artistic Liberty is Too Much?

I was browsing special collections two days ago and I found Romeo and Juliet Travestie: or, The Cup of Cold Poison, an 1873 version of the play with a surprising adaptation; this version is a burlesque, in one act. There are books that tell the stories of Shakespeare’s plays in condensed form, with modern language, and I have heard of plays (particularly Nahum Tate’s King Lear) that replace the ends of the plays with happier versions, or more family-friendly words and ideas (Thomas Bowdler’s The Family Shakespeare).

Even though this adaptation inspired disdain (in me), I think its existence is symptomatic of the fact that, at least as I see it, Shakespeare is no longer “just a playwright,” and hasn’t been “just a playwright” for a long time. The plays no longer mean the same thing they may have at the time of their creation; thinking about any of his works comes with the baggage of his name, what it means as a student or an actor to read/perform, any adaptations or even pop references one may have heard, and even the difficulty that can arise in trying to read such old English. His work is more of a jumping-off point than the end of the road. It inspires people, either to push harder with research, thought, or creative outpourings. Setting aside this burlesque, which still inspires in me a bit of hoity-toity attitude, I think this sort of movement is impossible to avoid, and, in many ways, is a really important piece of change and growth.

Welcome, Emma/Faces of Shakespeare

Hello, all.