There are so many elements and materials that Barbara Drake donated to The Claremont Colleges, those of us archiving can sometimes lose sight of the specifics. Until this week, I hadn’t spent much time looking over the primary education resources, except for when these materials were divided into subject specific categories weeks ago. However, this week when I became reacquainted with these materials, it brought to life the spirit of Indigenous education that Drake encouraged and centered in her own life.

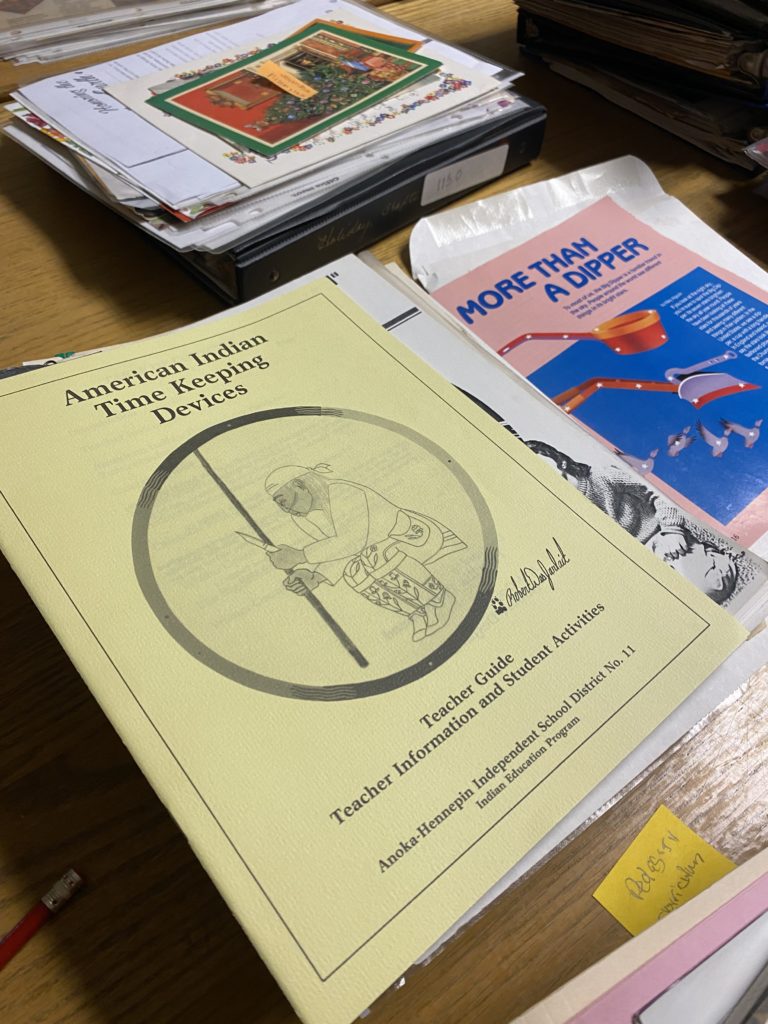

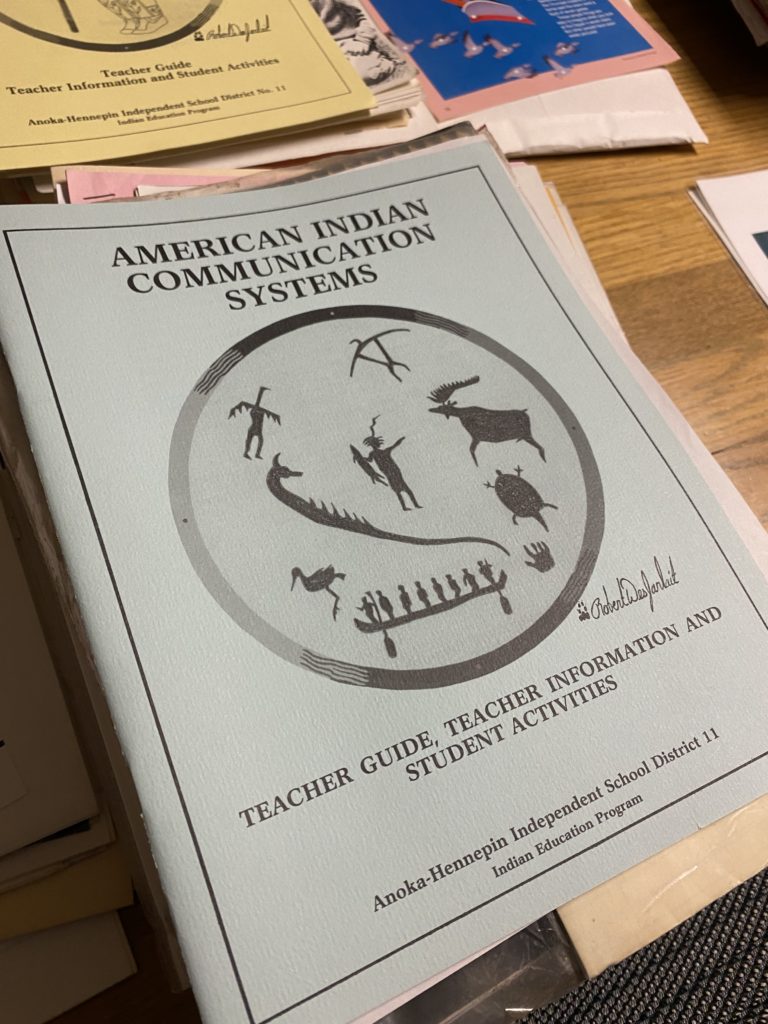

Needless to say, Barbara was passionate about educating every age group. However, in her materials there is an unmistakable emphasis on making Indigenous education available to primary school children. Not only did Barbara travel between Southern California districts and schools, hosting workshops and interactive lessons ranging in topic from traditional Native American housing to astronomy that incorporated an Indigenous point of view. In addition to these services, she also kept a meticulous variation of Indigenous centered pedagogies and teacher’s guides. These guides inform educators on how to center Native American perspectives, beliefs and traditions in primary school lessons. These pedagogies and guides touch on topics such as Indigenous time-keeping, astronomy, language, math, music and many more.

Plainly stated, Barbara made an effort to retain education guides on how to center Indigenous voices and perspectives in just about any primary school lesson. It cannot be overstated how important these resources are. Children of Indigenous heritage are rarely catered to in terms of educational representation, Barbara’s materials make a serious, and much needed, attempt to correct that.