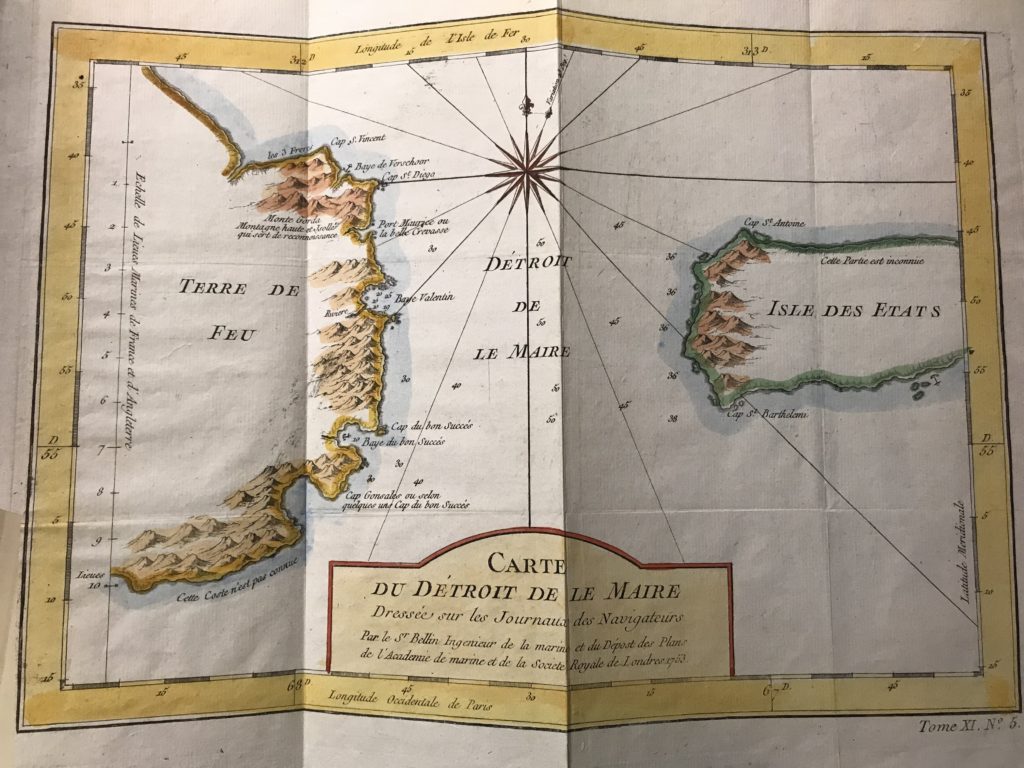

For about 100 years, sometime after 1622, mapmakers portrayed California as an island. Among the history of cartographic errors this is always one enjoyed in US scholarship–becoming a comedic synecdoche in CA’s political history. Uniquely, and perhaps adding to the enigma of the story, the error has an origin. The culprit was Juan de la Fuca.

There is perhaps nothing entirely new in this bit of trivia. But in studying many of these maps, I am often left astounded by their detail. I fathom at the intricate and precise nature of these hand-drawn, works of art.

Without access to anything remotely similar to our cartographic technologies, how could they be done so well? I assume that many of the maps are palimpsest; or they build on a former version of the area. They are recursive. Like a sculpture fashioned over generations or by a multitude of hands, these maps arrive at a better understanding of the land through collective, historical paradox of iteration and revision.

Philosophically, this can send some into the deep end–maybe just speaking for myself. I think of simulacra in knowledge production. It seems ages and ages ago, but for over a century California was an island. That is a knowledge that would exceed my entire life. In a way, what we know, what knowledges we produce are islands. Then, over time, the map is redrawn.