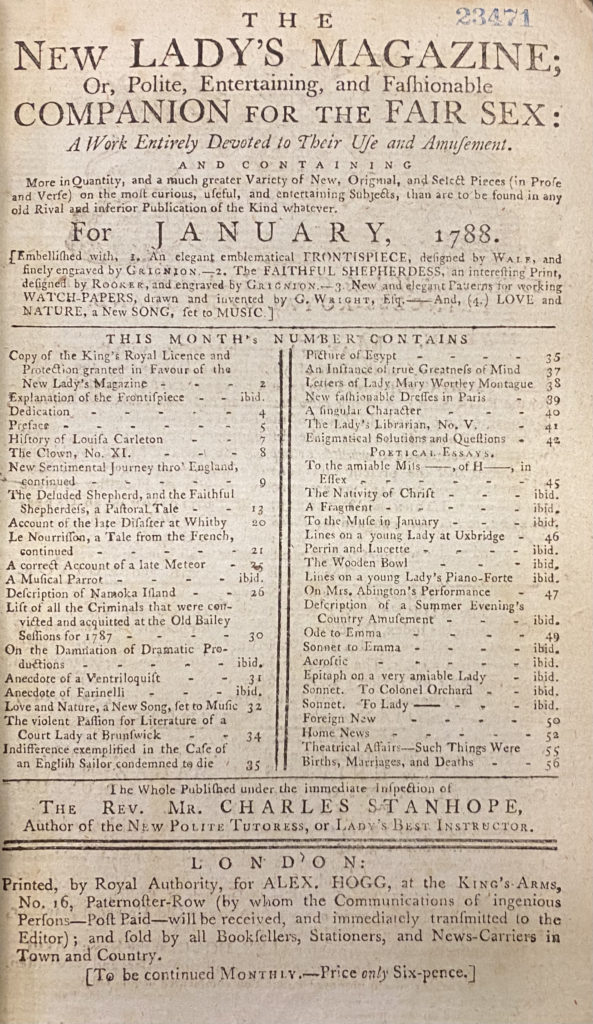

This week, I’ve touched women’s fashion magazines from as early as 1788, advertised as a “Polite, Entertaining, and Fashionable Companion for the Fair Sex,” and as late as 2022, flaunting an article on “The Real Dua Lipa: Optimist, Advocate, Pop Sensation.” Through these magazines, it is clear to see that much has changed in the last 3 centuries. Political, economic, religious, and technological factors have shaped the structure of societies and the role of women within them.

Looking at these magazines through the philosophy of technology lens, I will isolate those aspects of change and continuity that are a result of technological innovation. The relationship between the individual and certain technologies informs many aspects of life. Some concepts that have jumped out to me this week are those of identity, trust, power, and values.

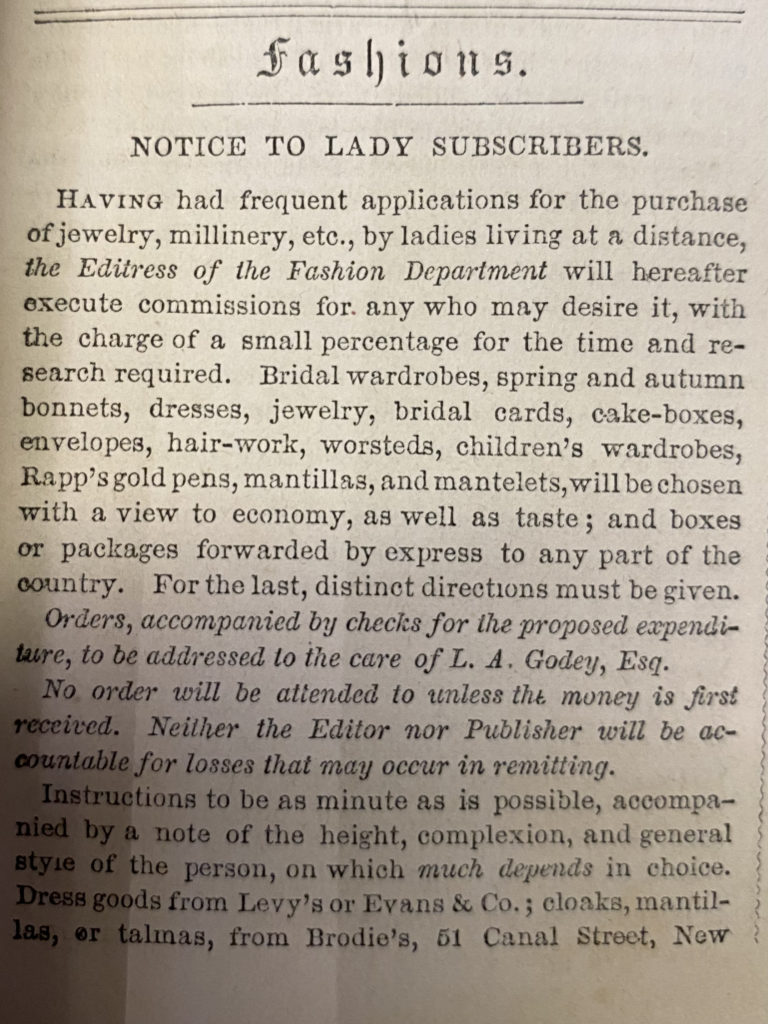

One thing I noticed as I viewed magazines from a broad temporal scope was the importance of gaining the trust of readers. Many women used fashion magazines to inform their decisions about what to wear and how to present themselves. Before widely available photographs made it possible to see what people were wearing in such fashion hubs as London and Paris, editors relied on detailed letter correspondence to learn about current fashion trends from those in Europe. They then shared these descriptions and drawings with readers, and readers trusted that they were accurate. One particularly fascinating article in Godey’s Lady’s Book (1855) advertised that fashion editors would pick dresses or bonnets for rural women and ship them from New York City for a fee. The women using this service were placing a large amount of trust in unnamed fashion editors via mail correspondence. As technology evolved, women no longer had to rely on fashion editors to buy dresses sight-unseen. Now, without leaving the comfort of their homes, women have access to almost every article of clothing available via online shopping. This leaves very little need to trust others in decisions related to fashion, which many consider to be an outward expression of identity.