This blog post entry was written by CLIR CCEPS Fellow, Lilyan Rock:

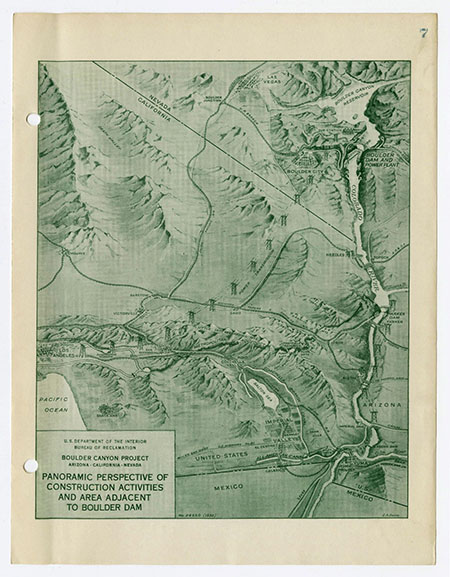

At the same time of the construction of the Hoover Dam (known as the Boulder Canyon Project during the All-American Canal era) there was also the completion of the Metropolitan Water District’s Aqueduct (1931-1935), connecting the newly harnessed water for a growing Los Angeles. The Metropolitan Water District serves all of Southern California currently, and their aqueduct system safely transports water over 242 miles through the desert sand.

This map shows how the construction of such an engineering feat happens while in progress, having intake, pumps and reservoirs constructed first, then pipeline completed afterward, shown as dotted lines on this 1932 map.