Disclaimer: This post contains images of historical documents, some of which include perspectives and language reflecting the time in which they were written. The Claremont Colleges Library does not endorse all the views expressed in these documents.

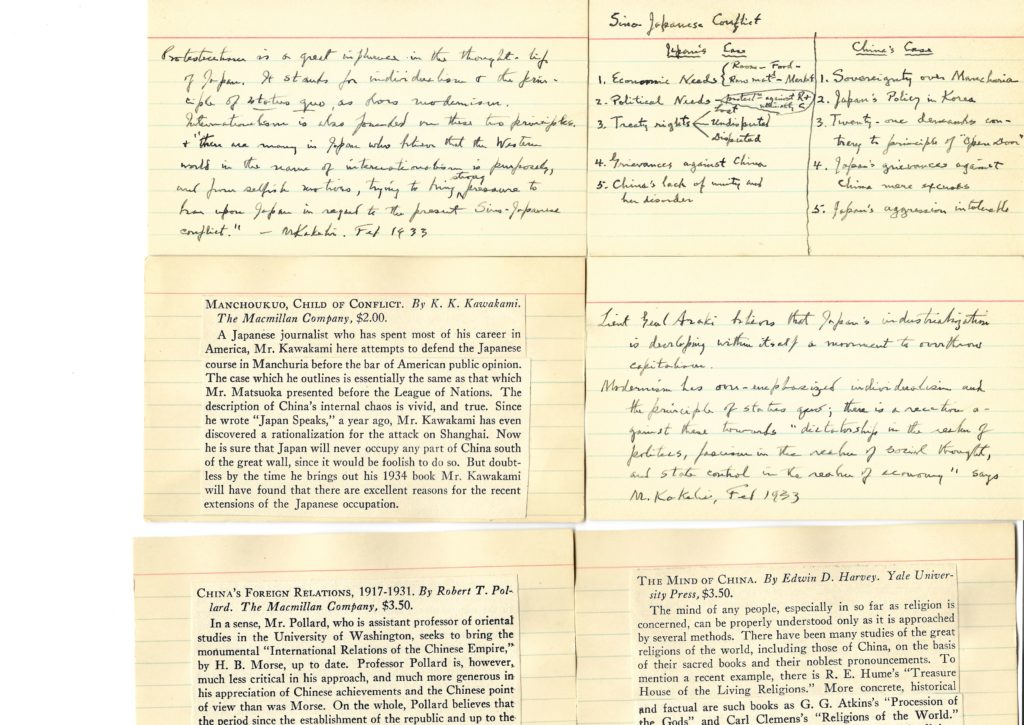

Newspapers, magazines, and other paper publications are important primary sources. As an outstanding historian, Ch’en Shou-yi preserved valuable publications. Two weeks ago, I briefly introduced Ch’en’s offprints, and this week I processed newspapers and magazine clippings, which Ch’en collected. Ch’en’s newspaper clippings and magazine excerpts dated from the 1910s to 1970s, covering many mainstream newspaper and magazine presses in both China and the United States such as the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Ta-Kung-Pao (大公報), Wen Wei Po (文匯報), and Shun Pao (申報). Ch’en had comprehensive interests in Chinese literature, history, linguistics, art, and education. In addition, Ch’en paid attention to contemporary global politics from the 1911 Revolution in China to the Cold War situations. I am impressed by some newspaper clippings on the news during the WWII because I found the participation and contributions of faculty, staff, and students from Lingnan University in Canton, China, and The Claremont Colleges.

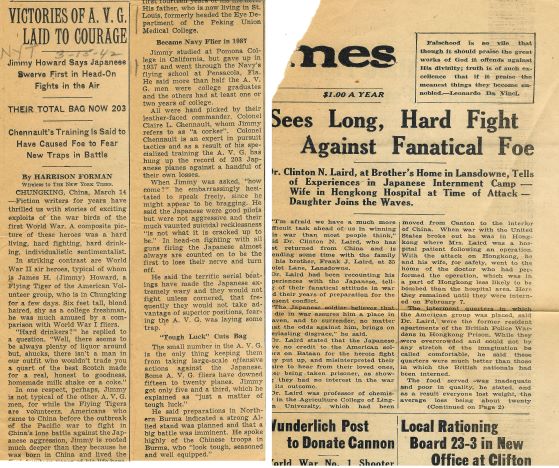

Dr. Clinton N. Laird was a chemist and the dean of Lingnan University, which was Ch’en Shou-yi’s alma mater. Mrs. Laird, a missionary nurse, also worked for Lingnan University, and was detained by Japanese invaders in Hong Kong after the breakout of the Pacific War in 1941. Some of Ch’en Shou-yi’s newspaper clippings focus on Mrs. Laird and other American citizens detained in Hong Kong, who were later released due to the pressure from American government. Dr. Laird wrote works such as Life in A Japanese Internment Camp and the Lairds participated actively in various public speeches to disclose the brutality of Japanese fascists and encourage American patriots to fight against fascists. (Ch’en Shou-yi’s booklets collections preserved related materials and I will introduce these in the future weeks). Ch’en’s newspaper clippings also describe Dr. Laird’s daughter, Miss Catherine Laird, who was born in Canton, China, and was able to speak Japanese. Having experienced Japanese invasion, Miss Laird fearlessly served the war work. In addition, Dr. Charlotte Gower, a female Professor of Anthropologists at Lingnan University, joined the United States Marines and became Capt. Charlotte Gower. After being released by Japanese troops as a POW, Capt. Gower told the public the life as a captive.

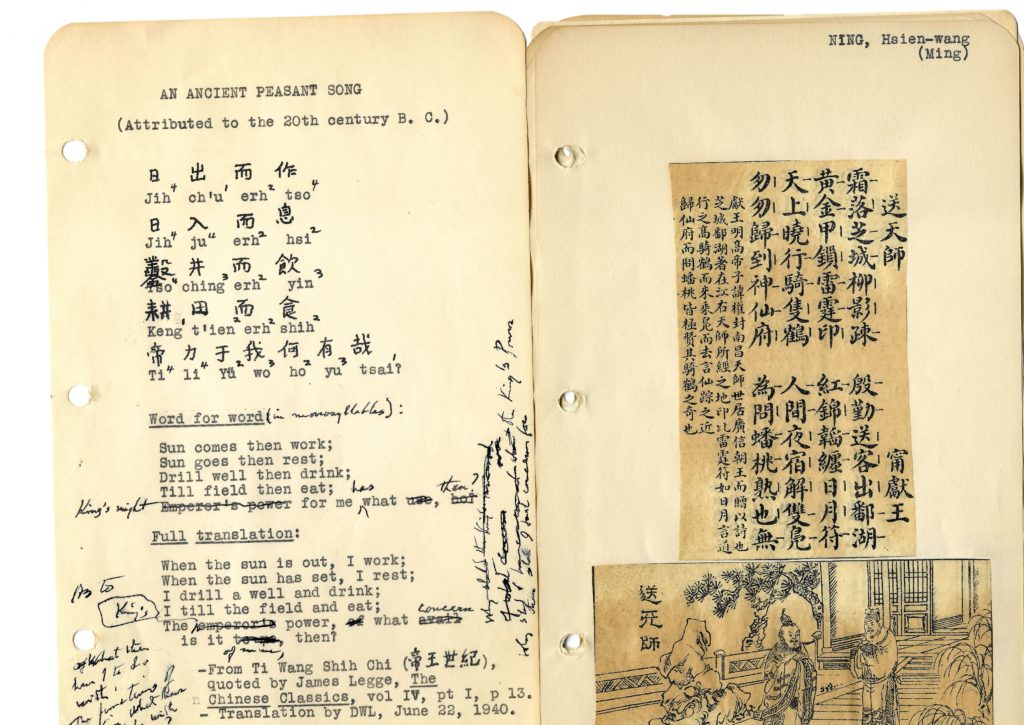

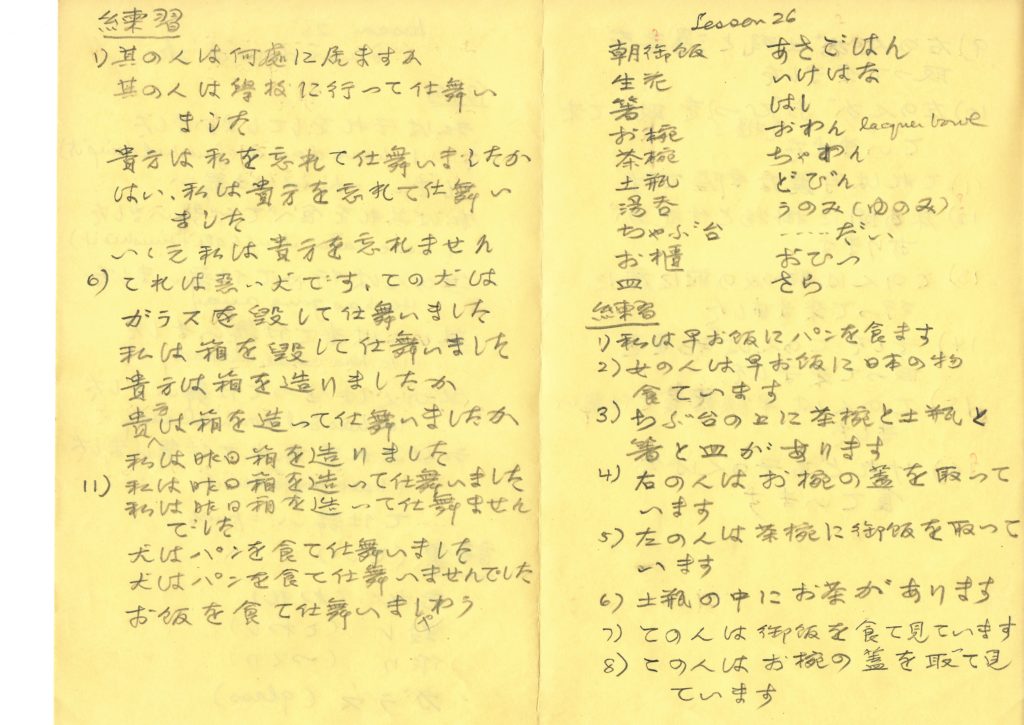

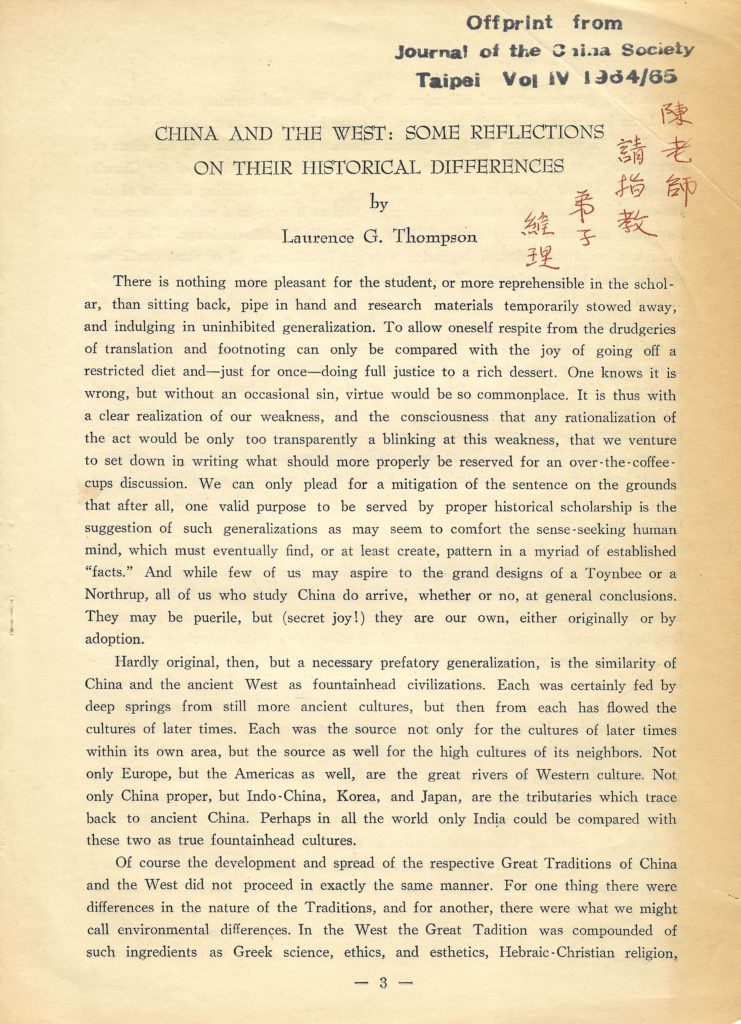

Students from The Claremont Colleges also contributed to a great extent during WWII. James H. (Jimmy) Howard was an alumnus of Pomona College. After graduation, he joined the AVG (American Volunteer Group) led by Colonel Claire L. Chennault, to fight against Japanese Army Air Force. The AVG, nicknamed the Flying Tigers, became famous for their campaigns in China and Southeast Asia. Laurence G. Thompson, whom I introduced two weeks ago, was another Claremont Colleges student and studied under Ch’en Shou-yi. Dr. Thompson was born in Shandong Province, China and got his Ph.D. from Claremont Graduate School (now Claremont Graduate University). During the WWII, Dr. Thompson served in the U.S. Marine Corps as a Japanese-language interpreter, and fought in the South Pacific. After WWII Dr. Thompson was well-known for his contributions to East Asian studies.

Scholars and students always have passion for the justice, empathy, and brotherhood for mankind. Ch’en’s newspaper and magazine collections recorded their contributions. Their sacrifice and glory should always be remembered.