A flower from England

Discover the Claremont Center for Engagement with Primary Sources (CCEPS)

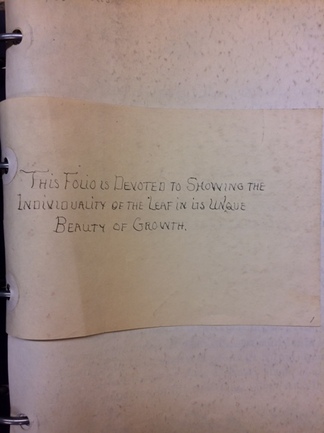

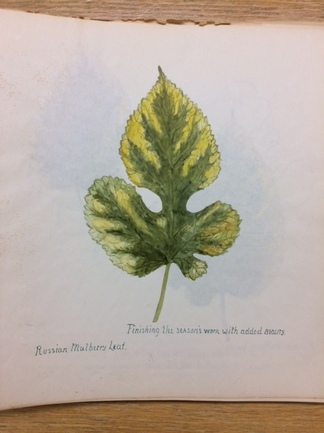

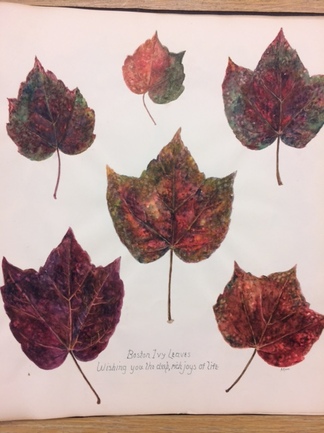

I took a break recently to help with the best kind of archival tedium: numbering the pages of old scrapbooks. The books were created by David French, a Pomona College student in the 1930s. French amassed several folios of his nature drawings and homespun poetry, with each volume dedicated to a different feature of the Claremont landscape (wildflowers and leaves were evidently his particular favorites).

French’s notebooks will soon become part of the Claremont Colleges Autograph and Manuscript Collection here at Special Collections. Lovingly made and steeped in a strong affection for poetry and nature, these folios provide a wonderful glimpse into the mind of a Pomona College student as he documented a much sleepier and more pastoral Claremont

It’s true! The 13th annual Los Angeles Archives Bazaar is happening this Saturday, October 20, at USC’s Doheny Library. This will be my first time attending, and I can’t wait to explore what’s sure to be a diverse and exciting array of L.A.-centric primary sources. I’m also looking forward to hearing from our colleagues Lisa Crane and Sara Chetney, who will open the day with a presentation entitled “Researching L.A. 101.” You can find out more about the Archives Bazaar here.

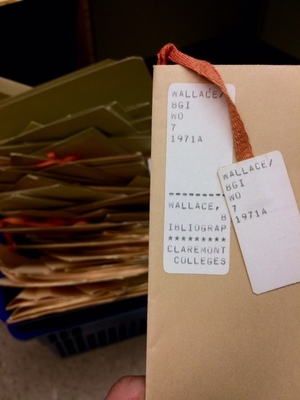

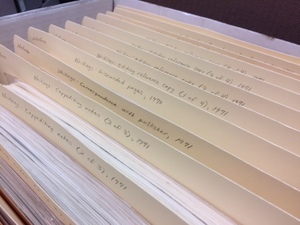

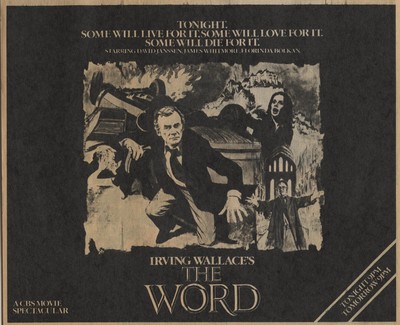

Back here in CCEPS land, my work with the Wallace collection proceeds apace. The collection’s peculiar, library-style processing scheme–a legacy of Honnold Library’s initial foray into computers in the 1980s–requires wholesale reprocessing according to archival best practices. As you can see from my photographs, reprocessing for The Word series is just about finished, and we’ll soon have the finding aid online and the materials available for research at Special Collections.

The Wallace collection contains materials from dozens of more books, so our work on The Word represents just one small step toward the eventual goal of complete reprocessing. But it feels good to commence the stepping nonetheless!

The Irving Wallace collection is a rich resource for the study of American book publishing in the postwar decades. The series dedicated to Wallace’s 1972 novel The Word, for instance, contains five complete drafts at various stages, multiple folders of copy-editing notes, and extensive correspondence between Wallace and his editors at Simon and Schuster. These documents provide a granular picture of the intellectual labor involved in the publishing process.

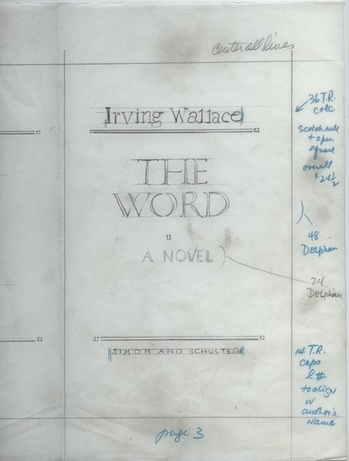

Yet publishing also involves questions of design, as evidenced by this mock-up made by the production department of Simon and Schuster in 1971. While not remarkable in and of itself, this item testifies to the full spectrum of processes–from writing to editing to design to marketing–which shaped an Irving Wallace novel.

These kinds of materials also offer fertile ground for historians of popular culture, who might question the aesthetic and political values embedded in the mock-up of the title page for The Word. What might the design reveal about the author’s (and publisher’s) intended audience? Do the design elements of Wallace’s books signal challenging polemical art or safe, middle-of-the-road entertainment? And was there a gap between the outward appearance of Wallace’s novels and the content contained within?

Hello again! It’s me Marcus! This Friday, I was very excited to return to working on the Yao Family Papers at CCEPS. I genuinely enjoy going through documents, photographs, and personal letters and gradually formulating increasingly wholistic pictures of members of the Yao family in my mind.

This week, I processed a series of the Yao family’s official documents that came in a black leather briefcase. These documents include Norman’s University of Shanghai diploma from 1936, Anne’s love letter to Norman from 1943, their British Hong Kong ID cards from 1950s, US immigration documents in 1956, naturalization documents in the early 1960s, and even Norman’s certificate of death in the 1980s. They marked not only the change in their legal status, but also told the personal stories of the immigrant family.

Finishing processing this leather briefcase marks the completion of my work on the first half of the Yao Family Papers with the exception of the photo negatives, which require special processing actions. I am very excited to bring the second half of the collection from the Asian Library to the CCEPS room and continue my exploration of Yao family’s stories!

Have a nice week!

Marcus

Before he made it big as a novelist, Irving Wallace spent the better part of a decade writing scripts for Hollywood films. His credits were unremarkable, and he found the work intellectually and financially unfulfilling. Nevertheless, Wallace would maintain connections to Hollywood for the duration of his career, and he apparently had few reservations about adapting his books for film and television. Starting with The Chapman Report in 1962 and continuing through CBS’s serialization of The Word in 1978, several of Wallace’s novels went on to enjoy a second life on the big and small screens.

Whatever their merits as art or entertainment, these adaptations highlight the cultural (and commercial) cachet of the Irving Wallace brand in the 1960s and 1970s. Whether in print or on-screen, his work seemed guaranteed to attract a large audience.

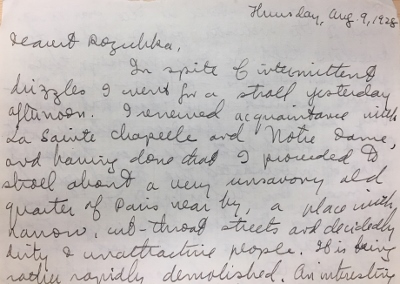

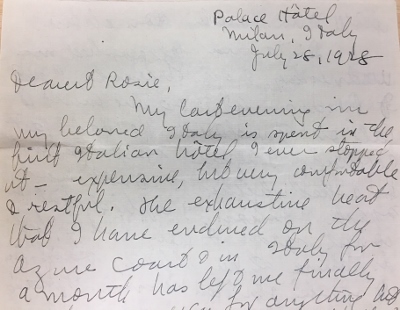

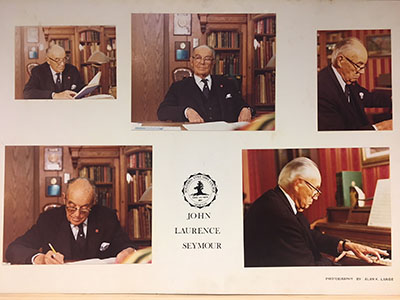

This week I worked on the processing plan template for Dr. Seymour papers trying to find the best way to organize the materials. There are lots of letters on different subjects. I am thinking if they should they be organized by dates, subject, name, or importance? These letters are like our present emails.

However writing letters on papers, in my opinion, has so much more value. First it requires to write it by hand, then mail it out, (take to the post office, buy stamps), then wait for the reply, and lastly (the most exciting part I think) receive the reply by mail. Today we receive emails in seconds but it was not the case. It took days, weeks, even months. After all this effort how disappointing it must be when the reply was not as expected or rejecting. Dr. Seymour received some replies from publishers who rejected to publish his plays for various reasons. Still, it didn’t slow him down to write another play or opera. He is a good example how not to get discourage. Last week I posted a picture from his childhood, here is Dr. Seymour as the professor at Southern Utah State College in Cedar City.

In 1973, fresh off the publication of The Word, Irving Wallace gave a lengthy interview to the Journal of Popular Culture in which he discussed his approach to research and writing, his popular success, and his frustrated relationship with literary critics. The interview offers a clear picture of Wallace’s sharp intellect and wide-ranging curiosity; one minute he’s discussing a recent academic study on the social effects of pornography, and the next he’s meditating on the lingering influence of America’s puritanical culture. The interview confirms my growing sense that Irving Wallace was more thoughtful, funny, humane, and self-aware than the label “popular novelist” would indicate.

By far my favorite part of the interview, however, is Wallace’s recollection of an all-night, cocktail-fueled conversation he once had with the writer James Baldwin, in Cannes. In the interview, Wallace remembers telling Baldwin that he had just finished writing The Man, in which an African American man is elected President of the United States:

[Baldwin] looked at me with disbelief. “The hell you have. What credentials do you have to do that? How can you write about a black man?” I said, “The same way you were able to write about a white man in your last novel.” He said, “Fair enough.”

According to Wallace, he went on to stress how, as a white writer with a massive audience, he could impact white attitudes about race more readily than Baldwin could hope to — and, moreover, that he had a moral obligation to try.

Baldwin’s reply? “I hope it works.”

For me, this exchange offers a new glimpse into the politics of Wallace’s work, and offers yet another potential avenue which scholars might use to approach him, his work, and his audience.

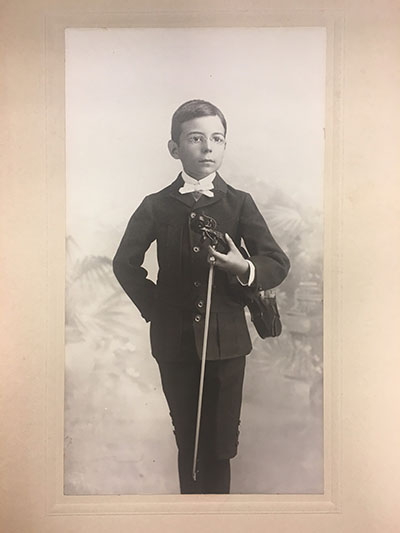

I am really impressed with Mr. Seymour’s papers. He wrote so much during his lifetime; not only operas and plays but also so many letters, diaries, lectures, and educational materials. While thinking about all his achievements I just picture him as an adult, a serious person. I forget that once, as everyone else, he was a child.

This picture of Mr. Seymour as a child with his violin really surprised me and made me think about his childhood. Except for this picture, there are not many materials from his childhood in the collection, but the violin truly fits him and I have no doubtmthat the practiced a lot!