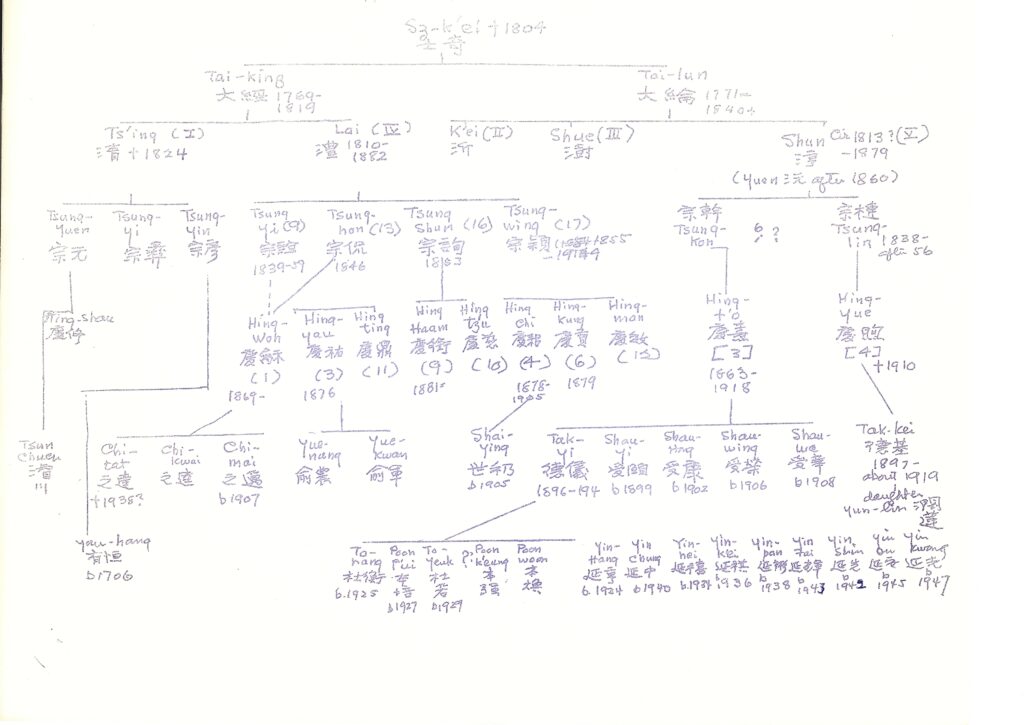

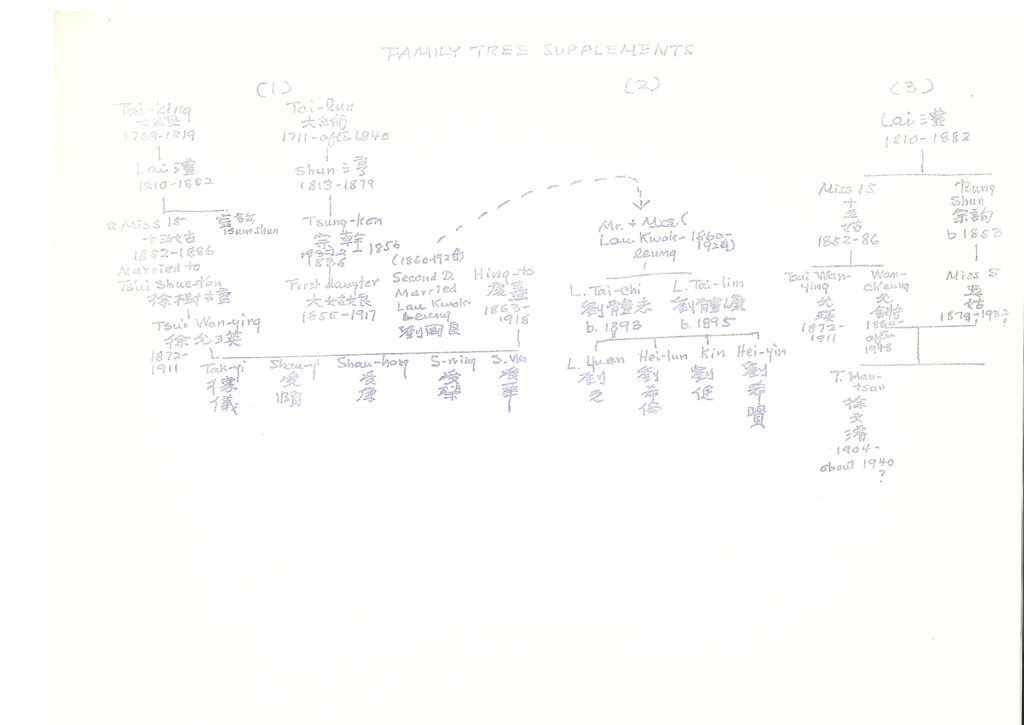

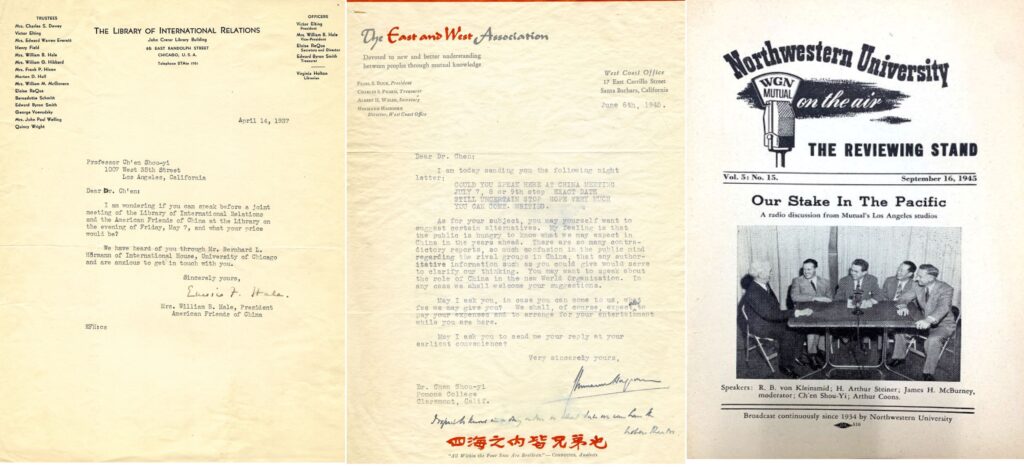

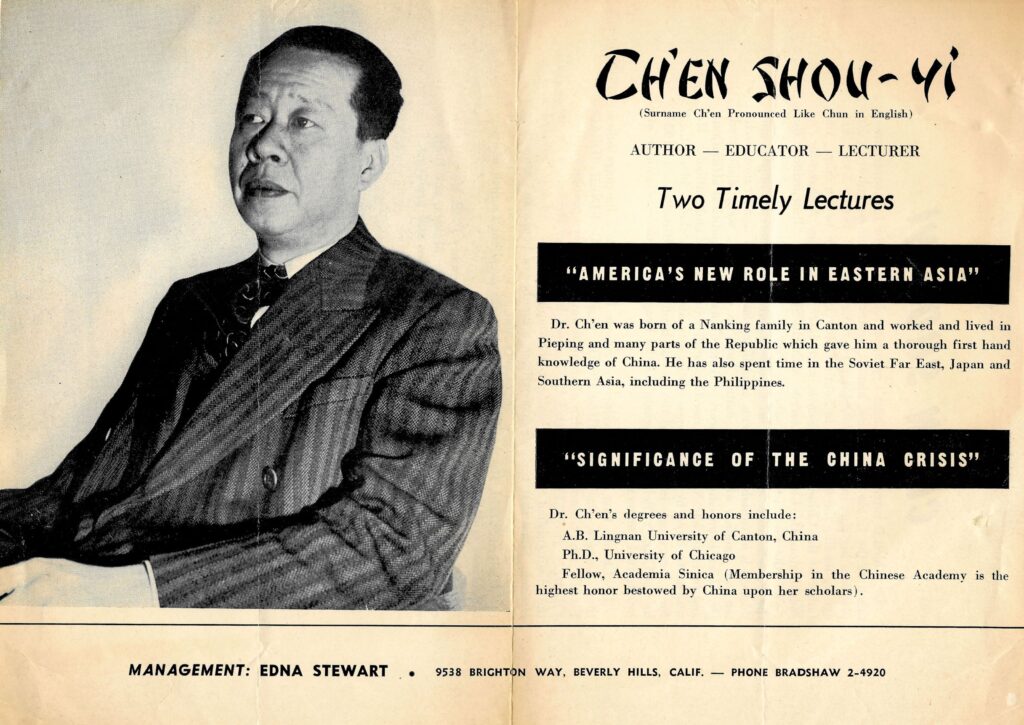

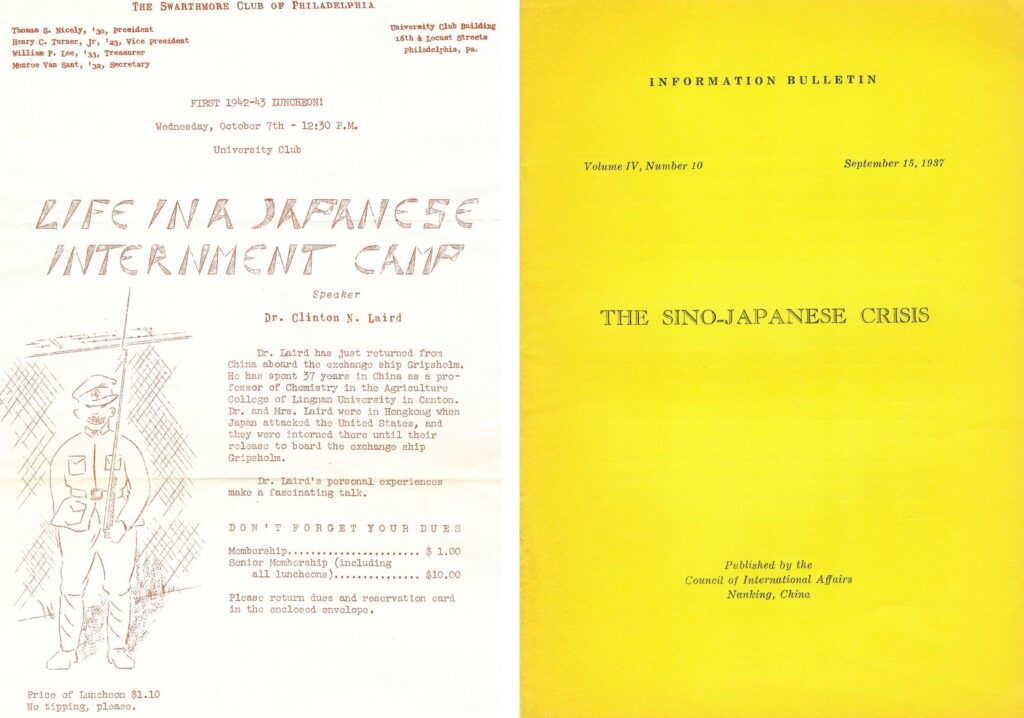

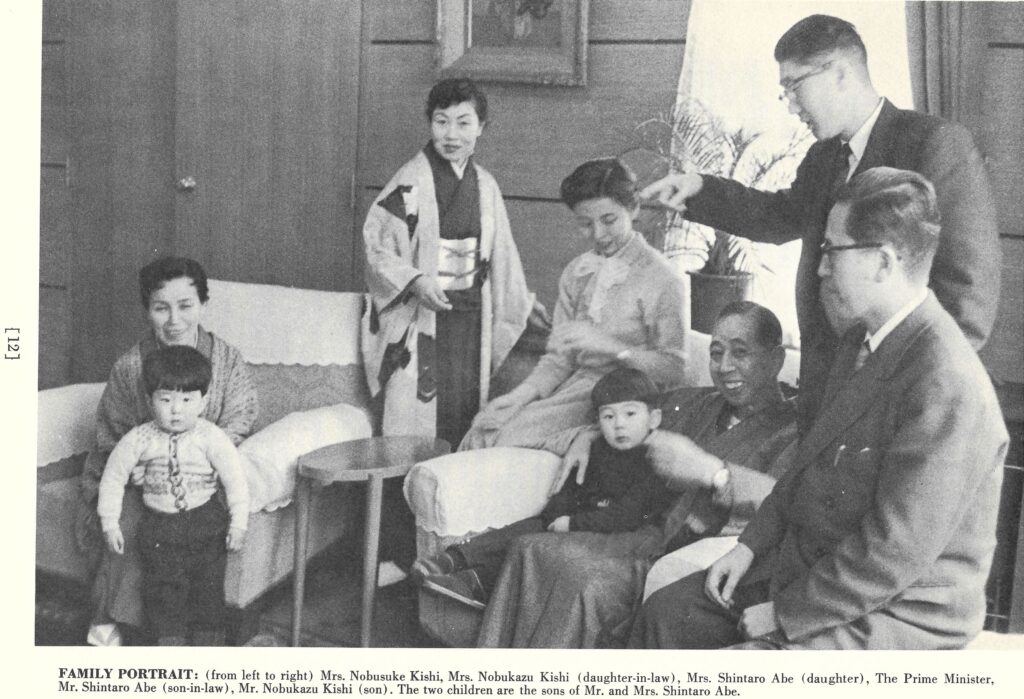

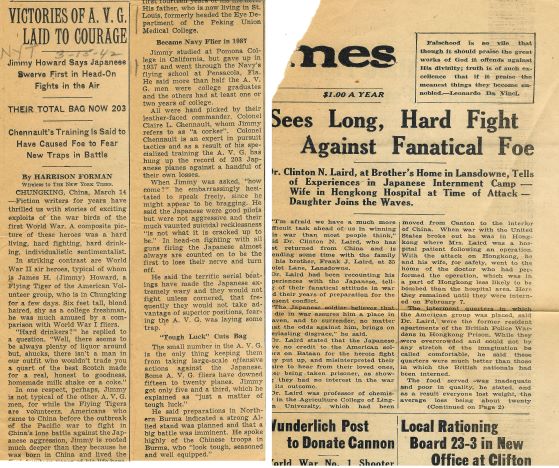

Lingnan University (嶺南大學) and its predecessor, Canton Christian College (嶺南學校) played important roles in Ch’en Shou-yi’s life. Ch’en and his brothers completed their undergraduate programs in Lingnan and Ch’en taught there before teaching in Peking and the US. Even though Ch’en never got a chance to return to his alma mater coming to the US during WWII, Lingnan still occupied his life with its alumni and faculty network. Many people we have introduced in the past weeks had deep relationships with Lingnan. Chan Wing-tsit (陳榮捷), Ch’en’s colleague at the University of Hawaii as well as lifetime friend, was an Lingnan alumnus. Dr. Clinton N. Laird (Chinese name: 梁敬敦), famous American chemist, served as a Lingnan faculty member with his wife and daughter, who were interned by the Japanese in Hong Kong during WWII. Lau Tai-chi (劉體志), Ch’en’s cousin, was also a Lingnan alumnus. Additionally, Lau’s father, another famous dentist like Lau, participated into the foundation of Lingnan. This week I processed Ch’en’s collections of photos and images, which recorded the history of Lingnan University and the glory of great Chinese and American figures who contributed to Lingnan.

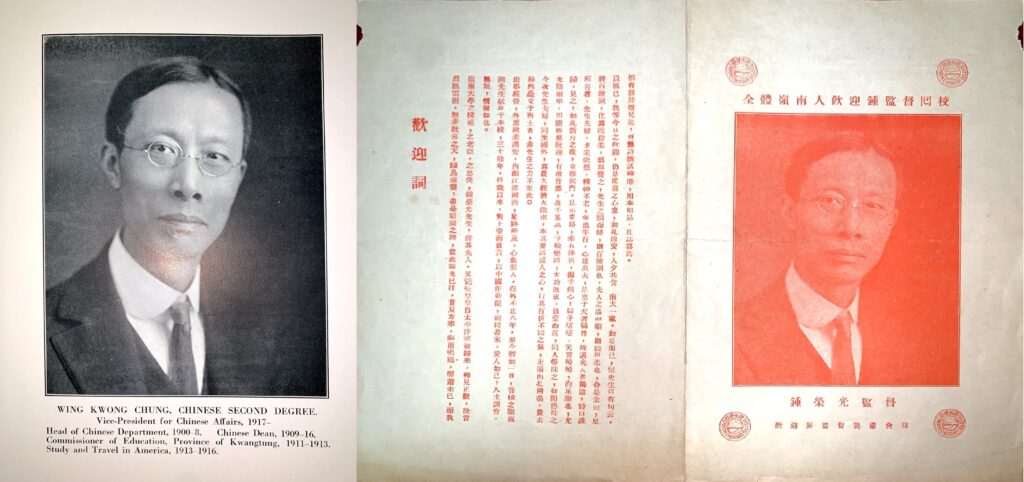

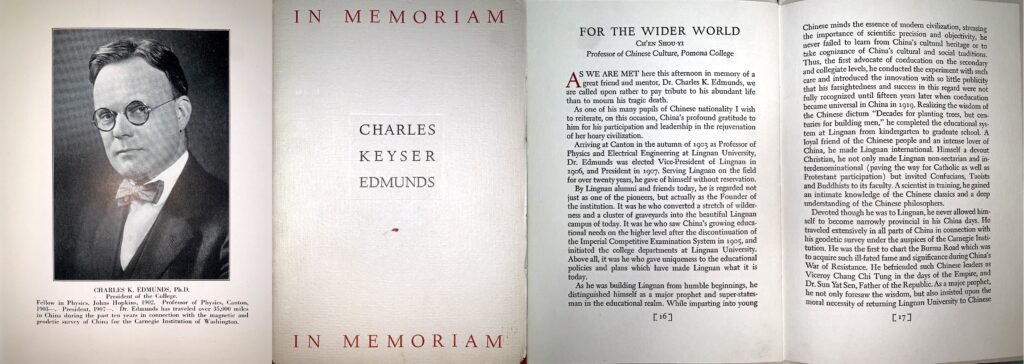

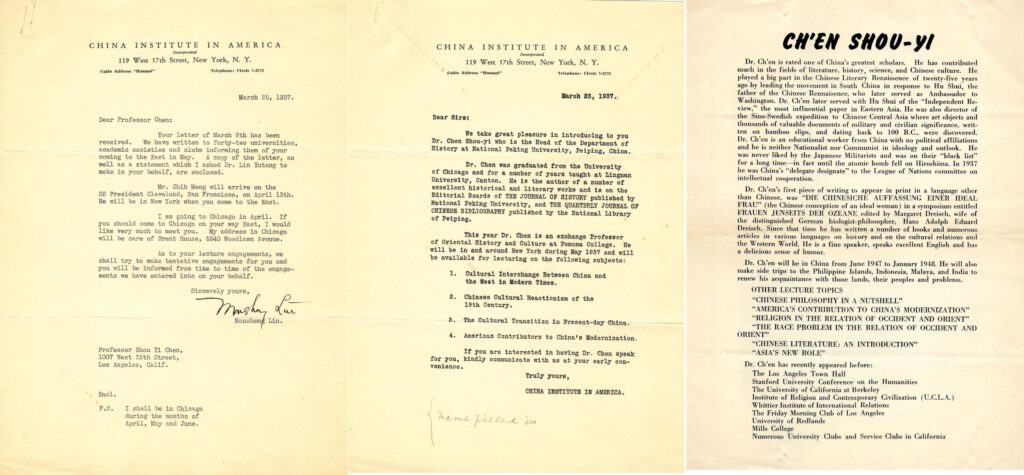

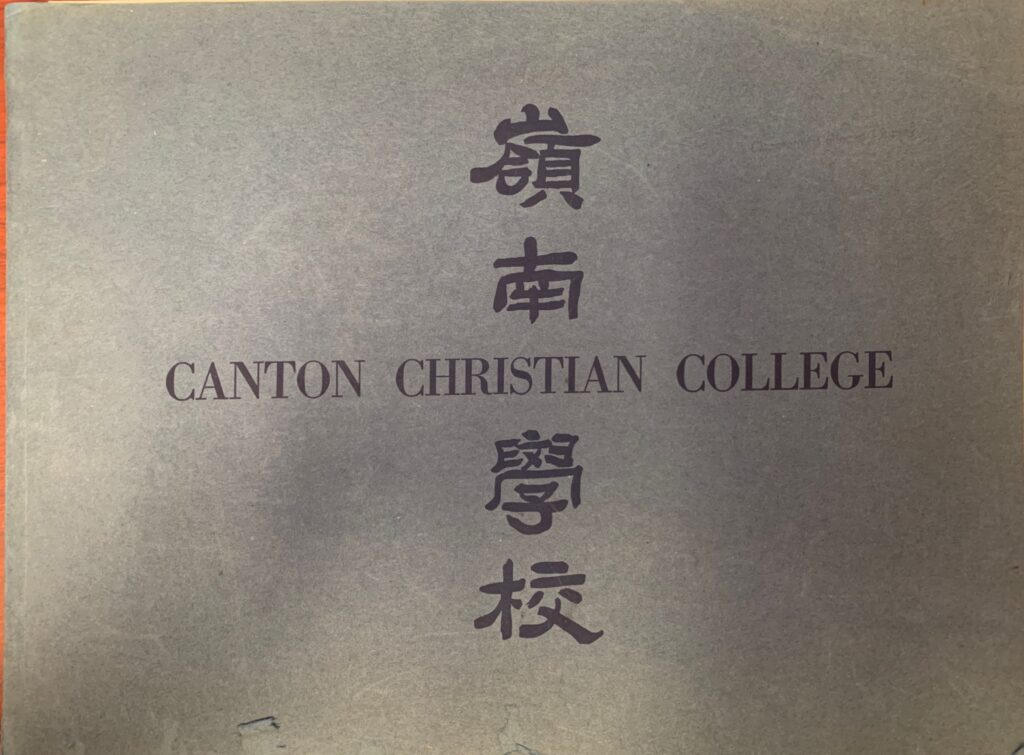

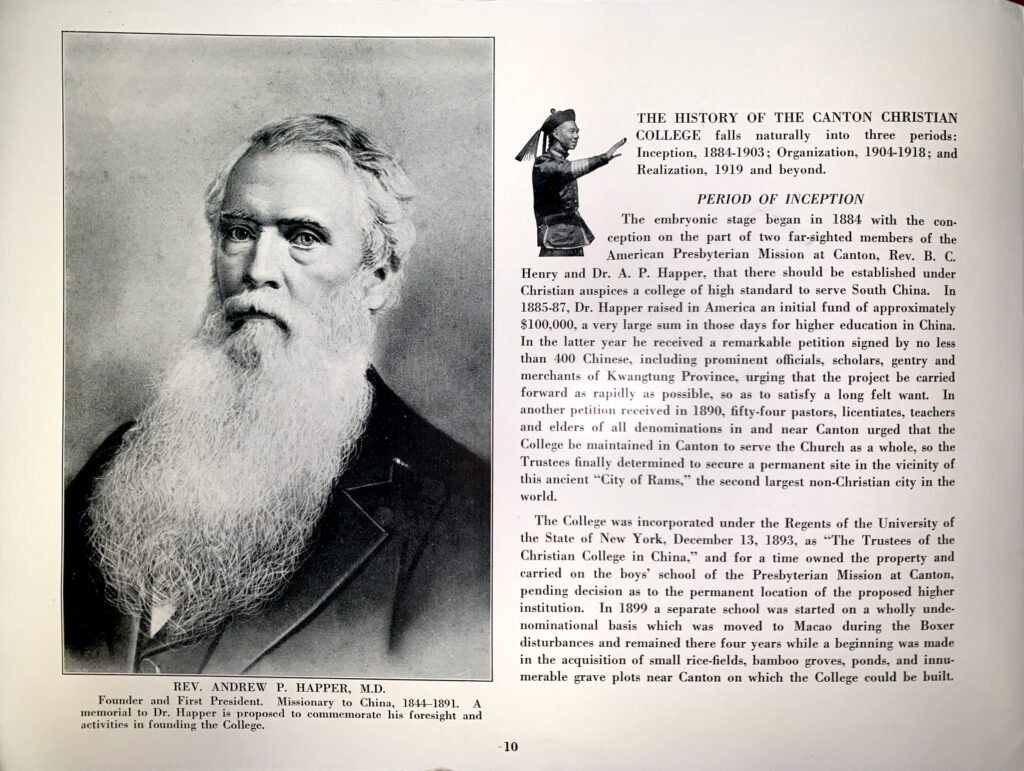

The brochure, Canton Christian College (嶺南學校), was likely published between 1903 and 1927, because before 1903, Lingnan was called Christian College while after 1927, Lingnan was transformed into Lingnan University (hereinafter referred to as Lingnan). This brochure introduced the inception and development of Lingnan. Lingnan was established by American Presbyterian missionaries Rev. B. C. Henry and Dr. A. P. Happer in Canton City, Kwangtung (Guangdong) Province, in 1888. Due to financial conditions and unstable domestic situations, Lingnan was relocated to Macau and Hong Kong. This brochure also introduced some revolutionary figures such as Dr. Wing Kong Chung (鍾榮光), the dean and first Chinese president of Lingnan, and Dr. Charles K Edmunds (Chinese name: 晏文士), who became the president of Pomona College and invited Ch’en to teach there.

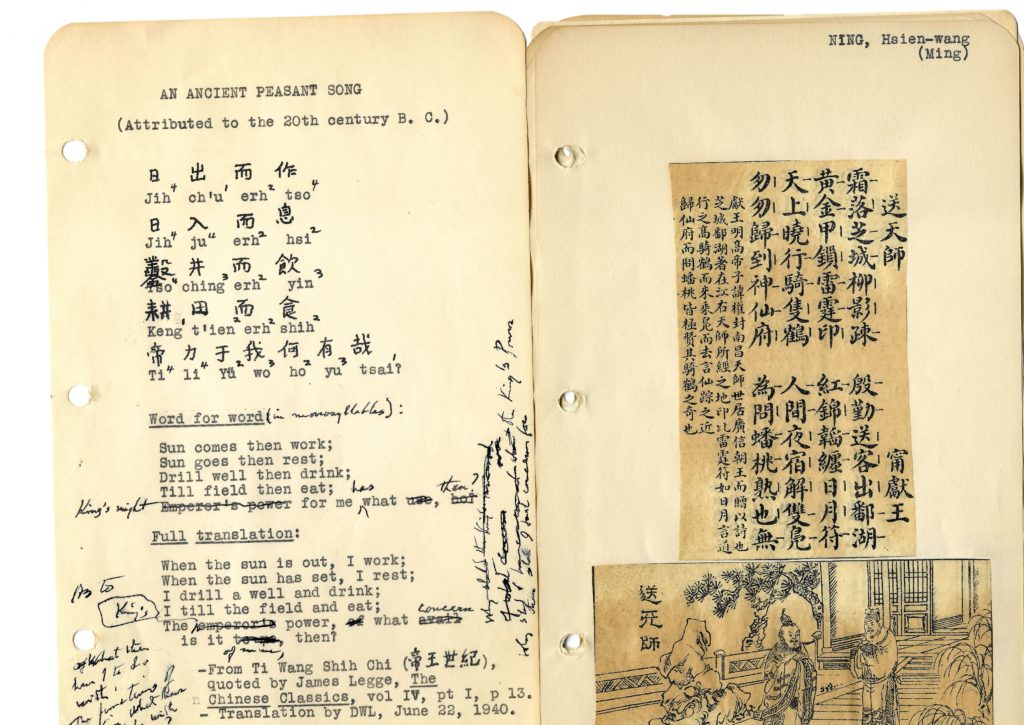

In 1911, Ch’en was admitted by Lingnan. In 1920, Chen taught at Lingnan after graduation. In 1925, Chen became an Associated Professor and travelled to University of Chicago to learn comparative literature. I think during this time, Ch’en maintained a deep relationship with Dr. Chung and Dr. Edmunds and witnessed their contributions. Dr. Chung raised funds among global Chinese diasporas and enhanced Chinese studies at Lingnan. Dr. Edmunds also accelerated a series of reforms at Pomona College such as supporting Ch’en to establish Asian studies after becoming the president of Pomona College. Lingnan was a missionary college, where many students, including Ch’en, attended to become Christians. Meanwhile, with the contributions of Dr. Chung and Dr. Edmunds, Lingnan preserved excellent Chinese studies and developed comprehensive subjects including science and physical education. Thanks to the diversity and tolerance of Lingnan, Ch’en was able to explore the communication of Christianism and Confucianism in his academic life. Lingnan also became a symbol of American missionary’s contributions to the Chinese modern education.