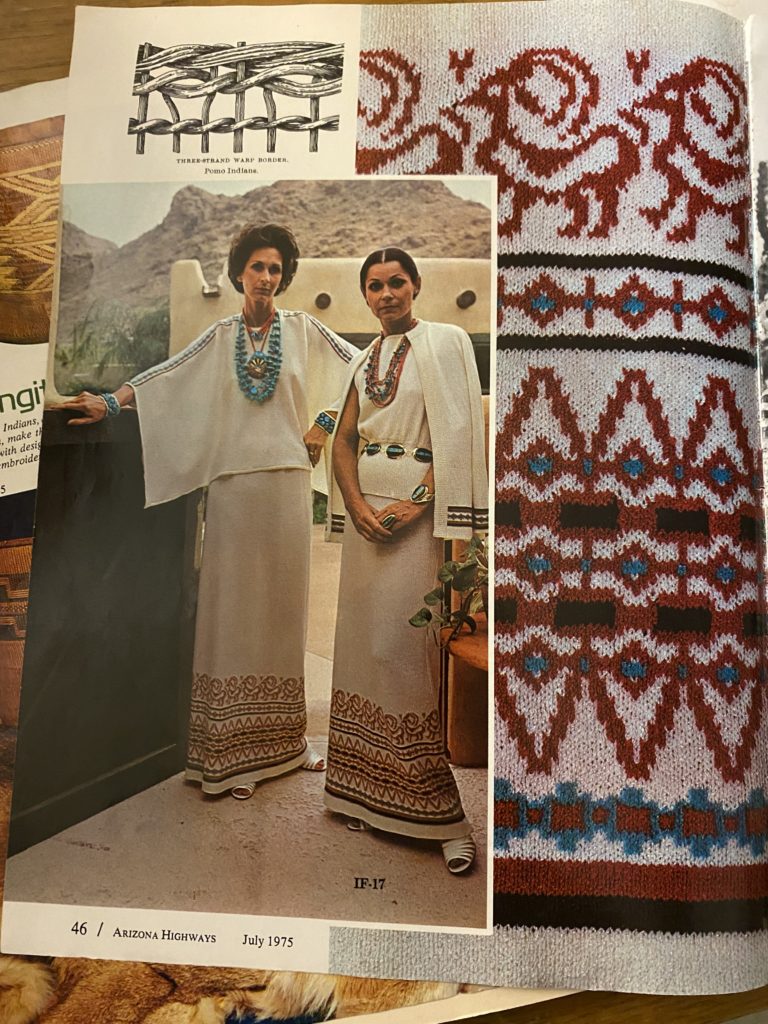

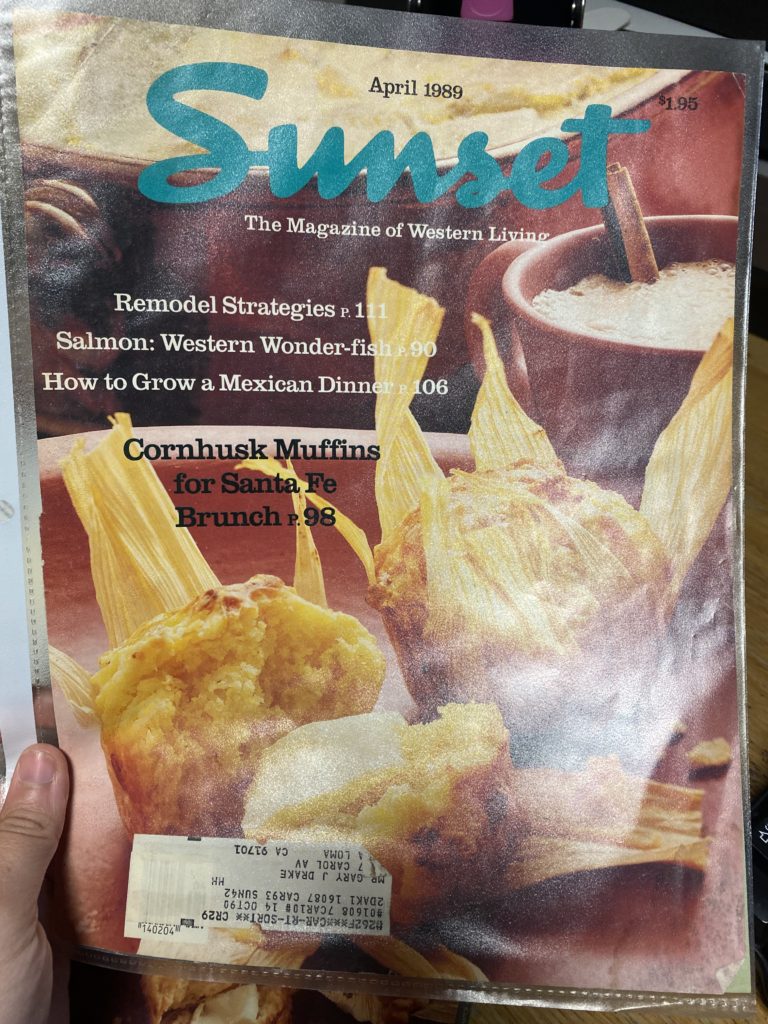

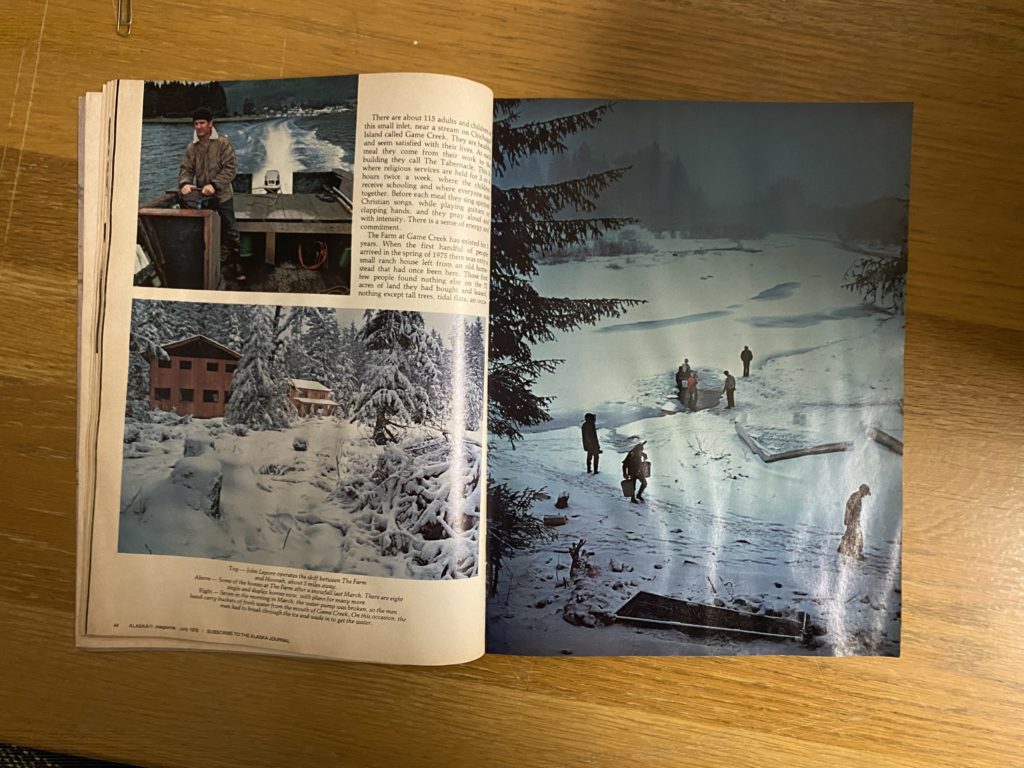

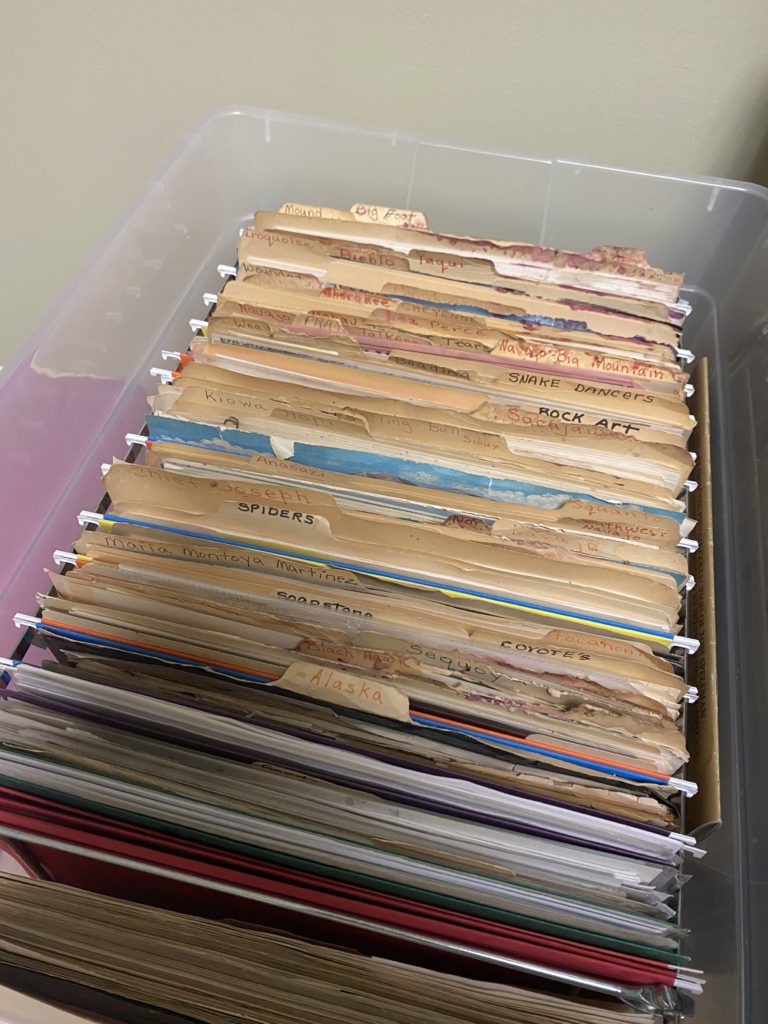

When I was a pre-teen I devoured magazines. I used to shuffle through the mail every day, hoping to find that the month’s issue of Seventeen, Teen Vogue or Allure had arrived. I admired the art of carefully curated images around an up and coming trend, intentionally beguiling and glossy. As I returned to sorting Barbara’s collection, I was pleased to find that she too enjoyed the comfort of a magazine. However, unlike the fashion magazines from my pre-teen years, the magazines Barbara preserved were much more profound. Rather than the pages weighing in on which lip gloss shade was perfect for summer, as mine had, the magazines from the Drake collection covered topics like accessorizing an outfit with Indigenous jewelry.

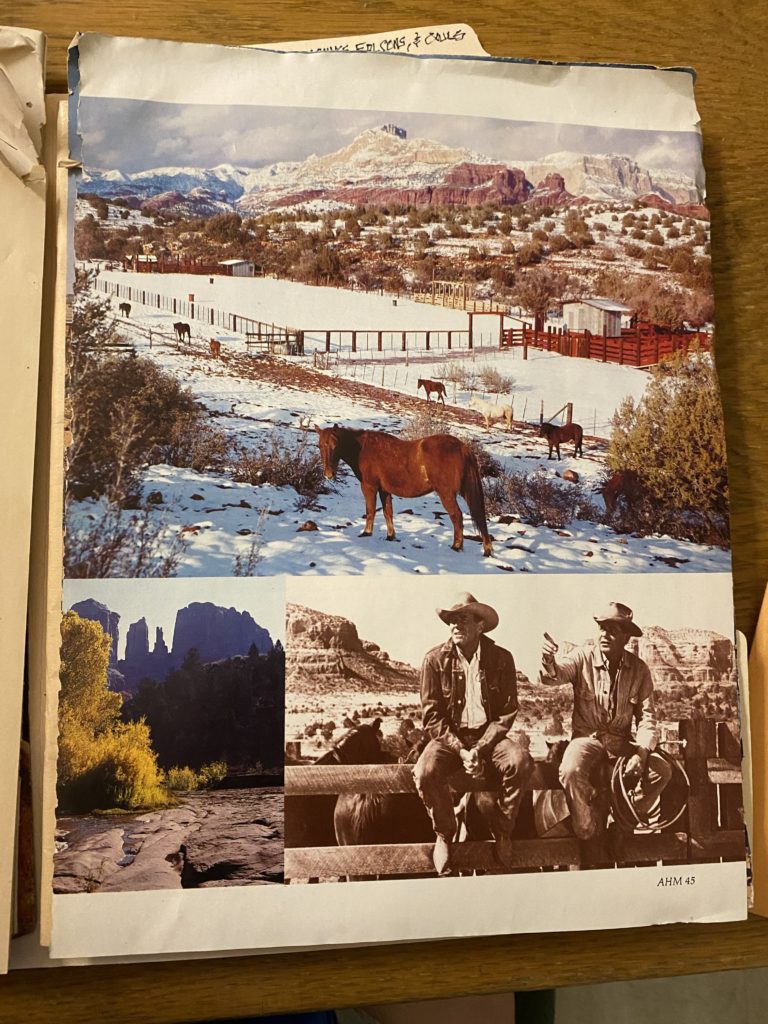

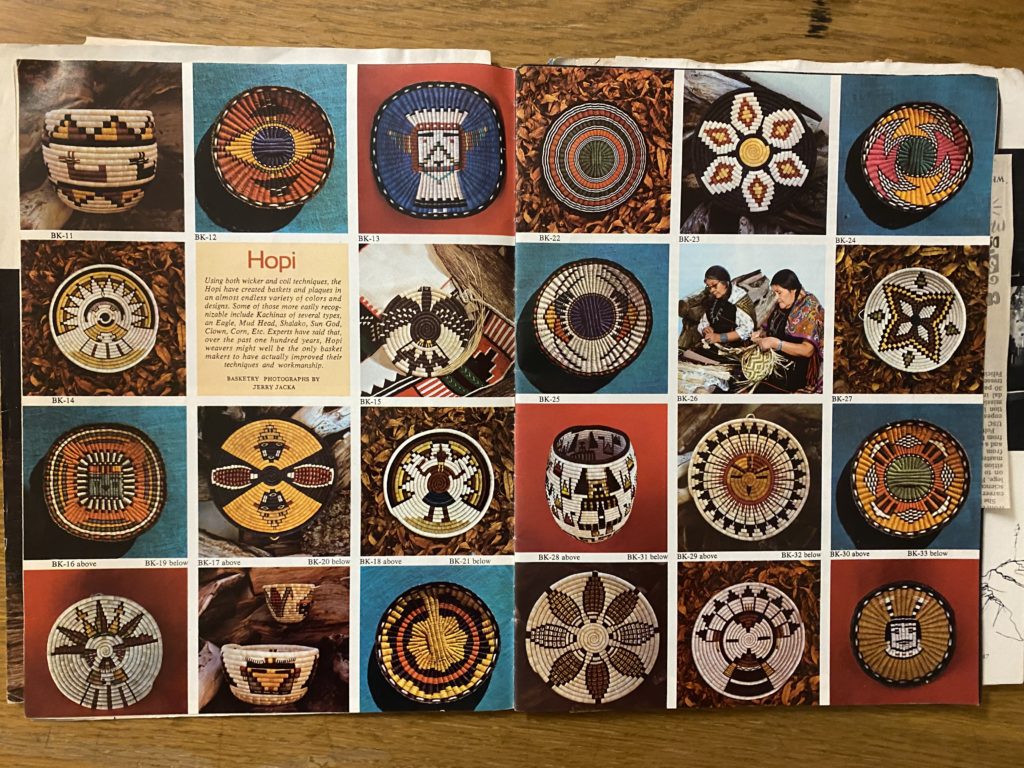

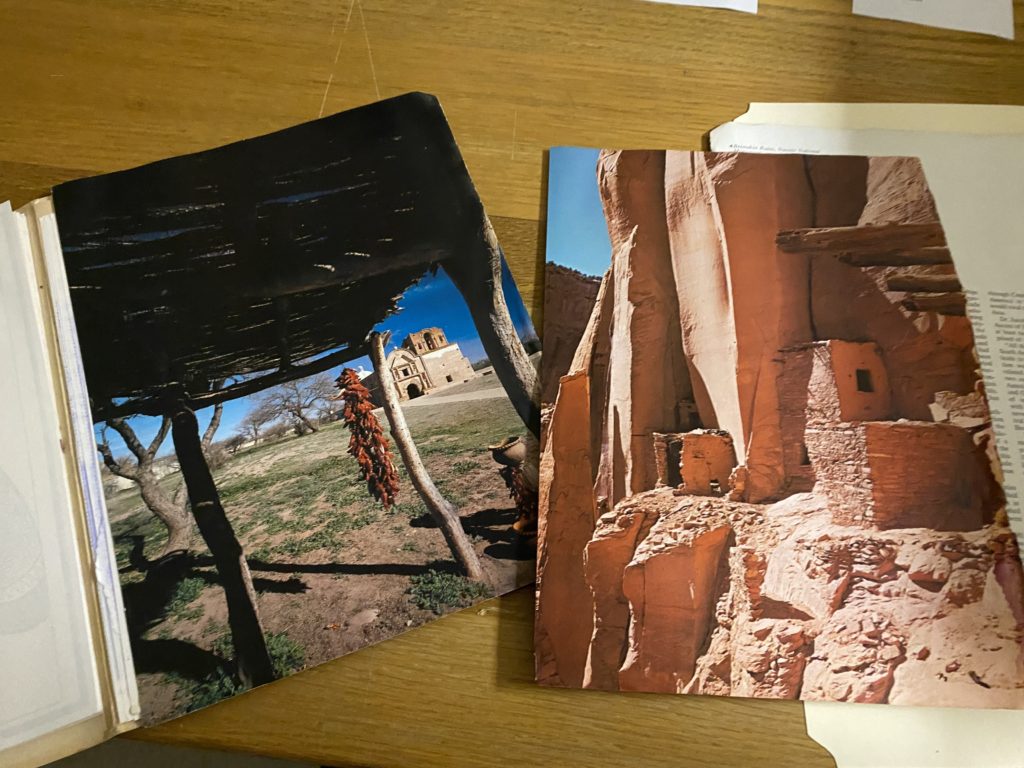

Specifically, Drake had preserved many issues of Arizona Highway, a magazine that has “captured the beauty and splendor of Arizona since 1925”. As someone who has only been to Flagstaff, the Grand Canyon and Phoenix once, through the publication I was exposed to landscapes of Arizona that I had not yet seen. More importantly, much of the content Drake saved touches on the Indigenous history of the land. Many of the photos capture Indigenous landscapes and visually pay homage to the cultures that founded the areas. Through reading her materials I learned about Arizona’s rich repository of Native basket weaving, whereby the traditions of the Hopi, Apache, and others are displayed through this medium. Consequently, they are more than baskets, they are fixtures of history.