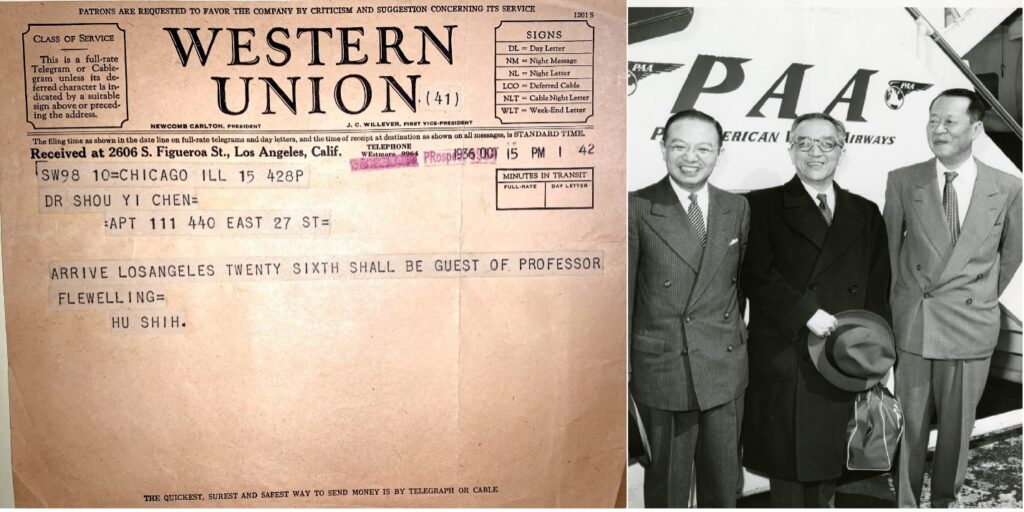

If we study modern Chinese history, Hu Shih (胡適) should be an inevitable name. As a scholar, Hu Shih introduced methodologies he learned in the United States to renovate modern Chinese history, philosophy, and literature studies. As a poet, Hu Shih wrote the first poem in modern vernacular Chinese (白話文), thereby affecting the reform of modern Chinese language. Hu, like most contemporary scholars, introduced democracy and science into China, trying to enlighten people and establish a liberal new China. As the representative of liberalist scholars, Hu and the founders of Chinese Communist Party, Chen Duxiu (or Ch’en Tu-hsiu, 陳獨秀) and Li Dazhao (or Li Ta-chao, 李大釗), participated in the New Culture Movement and May Fourth Movement to innovate Chinese culture and gain China’s independence. Mao Zedong (or Mao Tse-tung, 毛澤東) was Hu’s student. During World War II, Hu became a celebrated politician in Chiang Kai-shek’s administration and was appointed as the Chinese Ambassador to the United States. As a result, Hu maintained close relationships with both the liberal and conservative parties in China, not to mention numerous Chinese scholars including his lifetime friend, Ch’en Shou-yi. The Ch’en Shou-yi Papers has a box full of Hu Shih’s materials including Hu’s manuscripts, offprints, newspaper clippings, and cassette and recording tapes, all valuable materials to study Hu Shih.

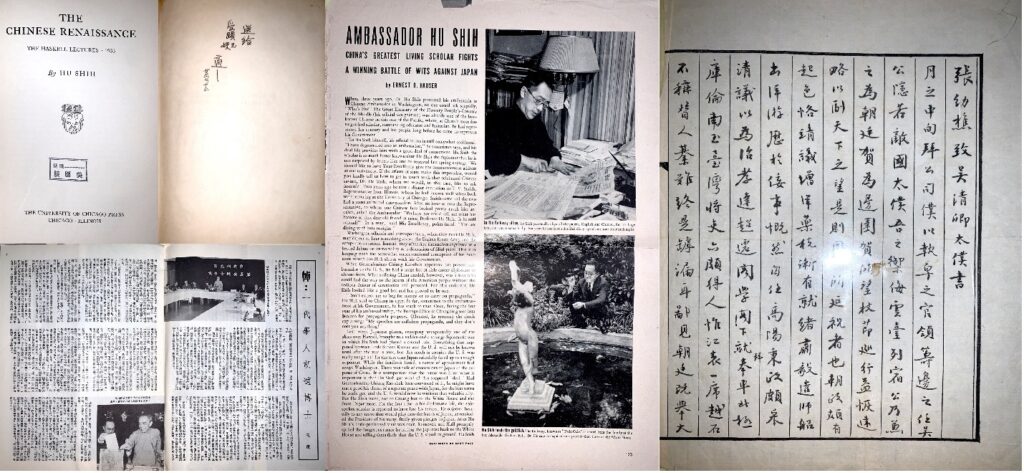

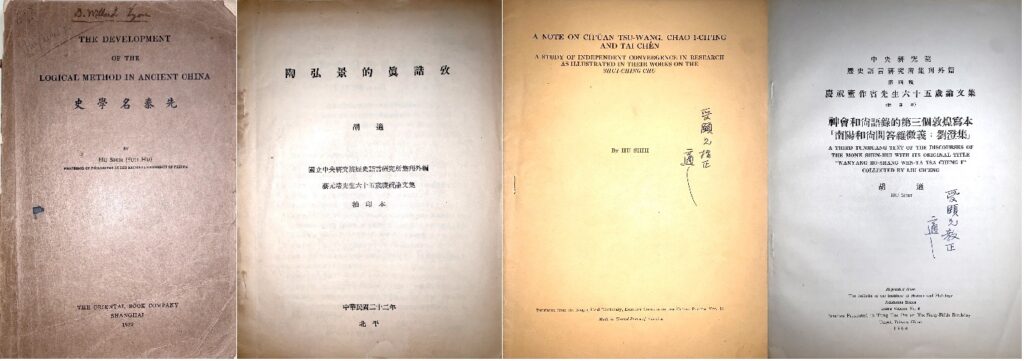

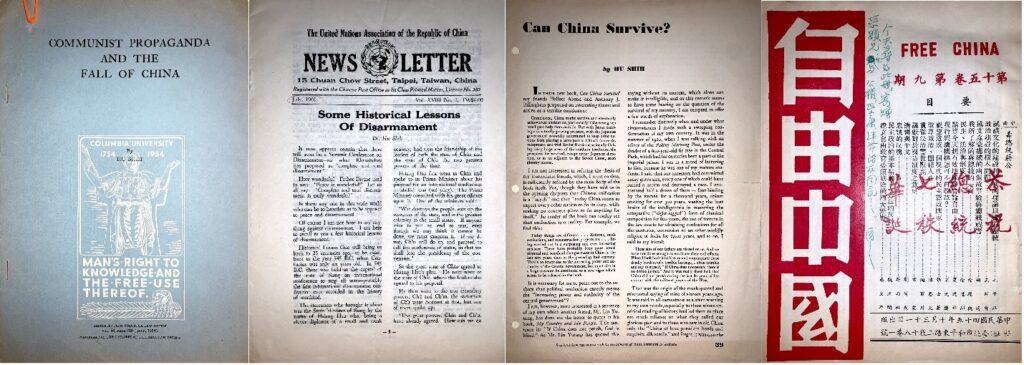

Hu Shih’s works in Ch’en Shou-yi papers includes Hu’s research on ancient Chinese philosophy like The Development of The Logical Method in Ancient China (先秦名學史), Buddhist studies like A Third Tunhuang Text of the Discourses of the Monk Shen-Hui (神會和尚語錄的第三個敦煌寫本《南陽和尚問答雜徵義:劉澄集》), and history studies such as Hsüeh Tsan, The Han-Shu Commentator (注漢書的薛瓚). Hu Shih also left two handwritten manuscripts on Chinese classics like Ch’ing-hsi wen chi hsü pien (青溪文集續編), and a published book, The Chinese Renaissance, likely a gift to Ch’en because of the handwritten compliments. In addition to academic works on Chinese history, literature, and philosophy, Hu also published his comments on politics such as China in Stalin’s Grand Strategy, and My Former Student, Mao Tse-tung. Ch’en also collected the magazine, Free China, which was published by Hu after retreating to Taiwan in 1949, and materials on the China Institute (華美協進社), which Hu helped found.

Ch’en also preserved special types of materials, such as cassette tapes and recording tapes of Hu’s speeches and lectures on Chinese literature and domestic political situations. One recording tape recorded Hu’s speech at a dinner during his visit to The Claremont Colleges. In the end, Ch’en collected newspaper clippings on Hu Shih, especially those reports on Hu’s death and contemporary well-known scholars lamenting the death of Hu. Hu recommended Ch’en to teach at the University of Hawaii, thereby introducing Ch’en to the United States. Hu was not only Ch’en’s lifetime friend and colleague, but also Ch’en’s faithful comrade in the publicity of Chinese culture and liberalism.