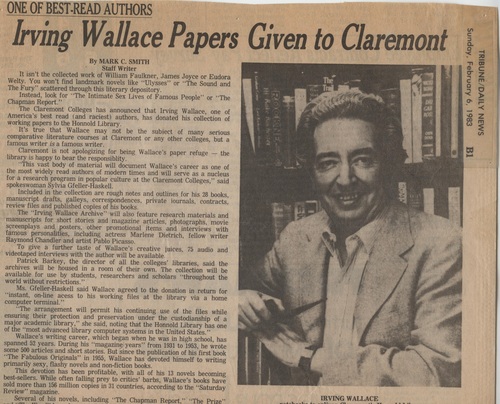

Irving Wallace was an incredibly prolific writer. Think Tom Clancy or Robert Ludlum and you get the idea. As I’ve continued processing the collection, I’ve learned some interesting things about Wallace’s writing style, his techniques, and his process. I’ve also gained a pet peeve or two about his idiosyncrasies.

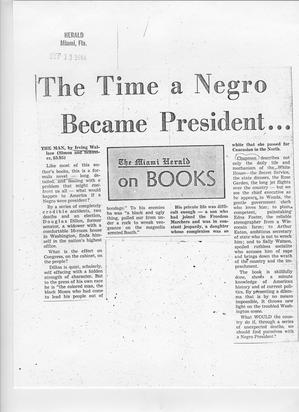

A few things I’ve learned in the last few weeks – Irving Wallace was either VERY interested in the topic of sex or he was VERY interested in making money with his work and knew that sex sells. Okay, it’s probably a combination of those things, but it seems like he’s always using sex as a major theme of his work. Last week I wrote about Victoria Woodhull, an exceptional woman who pushed back at the roles available to women during her era and even ran for president.

But because she was outspoken about her positive opinions of sex, Wallace labeled her the prostitute who ran for president. There was a lot more about the other women in the collection Nymphos and Other Maniacs as well. Promiscuous women make for good stories seemingly. As another example, in The Celestial Bed, Wallace’s story revolves around a man and woman who have sex with their clients to teach them intimacy and help them resolve their issues. I haven’t actually read the book, but that’s the gist I sussed from working with it. Wallace hit on a theme that worked and kept with it I think.

Another thing I learned about Wallace, like the theme of sex, he never seemed to mind reusing techniques that got a publishing contract. After placing numerous revisions of the manuscript for The Celestial Bed into new acid-free folders, I have now read pretty much the first paragraph of every chapter of the book. They all use the same formula. When (person’s full name) did (this thing: woke up, got to work, whatever), s/he had no idea that (this thing) would happen. It seems a bit cliché, but it works! Over and over I found myself wondering who was this cat Wallace was talking about and why didn’t he or she know that was going to happen. As a matter of fact, how did that happen in the first place? See what he did there? It’s called hooking the reader. Wallace did it well even if formulaically.

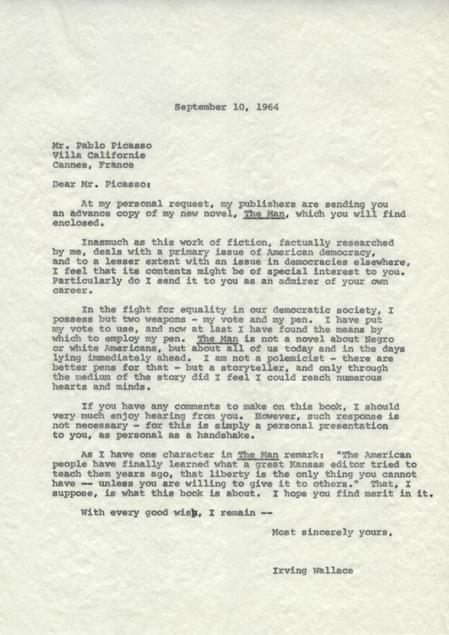

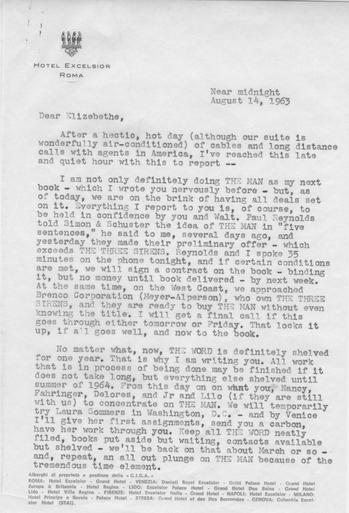

A last thing I’ve come to appreciate about Wallace in the last few weeks is just how well he understood his audience. As I’ve insinuated above, he knew his reader, but he even understood his other audiences. On each and every copy of his manuscripts I’ve worked with, Wallace has a little note attached explaining to the archivist and the researcher what this particular draft is about. He usually states how many revisions there were before the first draft that went to the agent or publisher to see if they wanted to buy it. Or how many more revisions were involved after he got that contract.

One manuscript I processed today was a draft copy for his wife to review. I cannot fathom it, but apparently she reviewed and edited every single manuscript he wrote. He always took her suggestions into account when revising. It astounds me that one or two years later, sometimes more, Wallace can still remember what every draft was about. Sometimes he cranked out entire books in a mere three months’ time all while working on other projects along the way. All of these things I appreciate, but even Irving Wallace can’t escape pet peeves.

Irving Wallace was an incredibly prolific writer. Think Tom Clancy or Robert Ludlum and you get the idea. As I’ve continued processing the collection, I’ve learned some interesting things about Wallace’s writing style, his techniques, and his process. I’ve also gained a pet peeve or two about his idiosyncrasies.

A few things I’ve learned in the last few weeks – Irving Wallace was either VERY interested in the topic of sex or he was VERY interested in making money with his work and knew that sex sells. Okay, it’s probably a combination of those things, but it seems like he’s always using sex as a major theme of his work. Last week I wrote about Victoria Woodhull, an exceptional woman who pushed back at the roles available to women during her era and even ran for president.

But because she was outspoken about her positive opinions of sex, Wallace labeled her the prostitute who ran for president. There was a lot more about the other women in the collection Nymphos and Other Maniacs as well. Promiscuous women make for good stories seemingly. As another example, in The Celestial Bed, Wallace’s story revolves around a man and woman who have sex with their clients to teach them intimacy and help them resolve their issues. I haven’t actually read the book, but that’s the gist I sussed from working with it. Wallace hit on a theme that worked and kept with it I think.

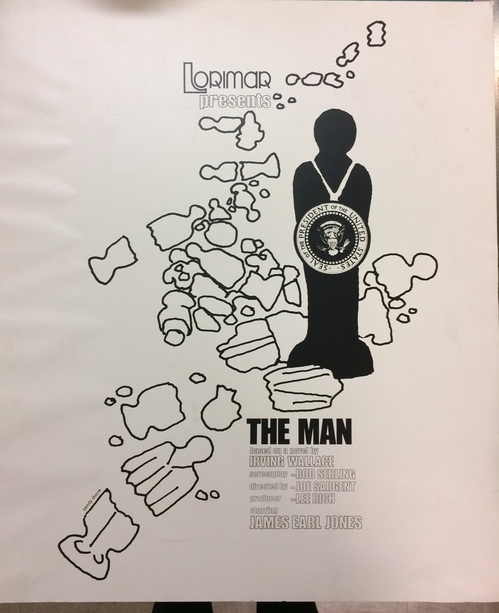

Another thing I learned about Wallace, like the theme of sex, he never seemed to mind reusing techniques that got a publishing contract. After placing numerous revisions of the manuscript for The Celestial Bed into new acid-free folders, I have now read pretty much the first paragraph of every chapter of the book. They all use the same formula. When (person’s full name) did (this thing: woke up, got to work, whatever), s/he had no idea that (this thing) would happen. It seems a bit cliché, but it works! Over and over I found myself wondering who was this cat Wallace was talking about and why didn’t he or she know that was going to happen. As a matter of fact, how did that happen in the first place? See what he did there? It’s called hooking the reader. Wallace did it well even if formulaically.

A last thing I’ve come to appreciate about Wallace in the last few weeks is just how well he understood his audience. As I’ve insinuated above, he knew his reader, but he even understood his other audiences. On each and every copy of his manuscripts I’ve worked with, Wallace has a little note attached explaining to the archivist and the researcher what this particular draft is about. He usually states how many revisions there were before the first draft that went to the agent or publisher to see if they wanted to buy it. Or how many more revisions were involved after he got that contract.

One manuscript I processed today was a draft copy for his wife to review. I cannot fathom it, but apparently she reviewed and edited every single manuscript he wrote. He always took her suggestions into account when revising. It astounds me that one or two years later, sometimes more, Wallace can still remember what every draft was about. Sometimes he cranked out entire books in a mere three months’ time all while working on other projects along the way. All of these things I appreciate, but even Irving Wallace can’t escape pet peeves.

My pet peeve with Wallace? Paper clips. Lots and lots and lots of paper clips. Mind you by now they’ve been replaced by archive-friendly plastic clips, but there seems to be no rhyme or reason for them. Why Irving?! Why did you bundle this set of pages together? And why didn’t you leave any inscriptions about them like you do about the drafts? Sometimes pages are bundled across chapters, sometimes within chapters. Sometimes he bundled huge swaths of papers (30-50 sheets at a time), while others he might choose to clip a mere three pages together. Was this where he stopped reading that day doing revisions? Was this where he stopped writing that day? Maybe, but who knows. It’s a little thing, but then pet peeves mostly are, right?