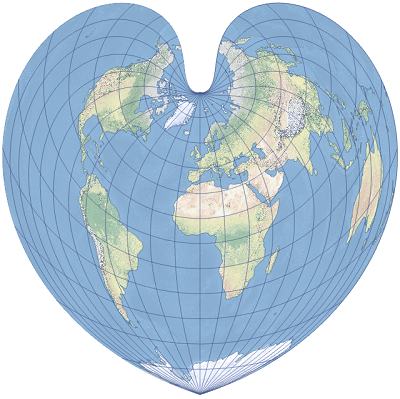

Hundreds of maps, pages depicting detailed accounts of cultures, stories and renderings of peoples and landscapes, instructions on preservation, and receipts of transactions from a single man’s interest, all contained in the three boxes. Each box just bigger than the next, like an Olympic ceremony podium. All of it to be stowed away in the permanent storage facility of a university thousands of miles and hundreds of years away from the original pen, or gaze, or idea.

With the arranging, encapsulation, itemization, and data input into ArchiveSpace, the journey is more or less over. The sense of incompleteness combined with achievement and relief feels ecological. It is a notion, a feeling I haven’t felt since my landscaping days. You tidy up, organize, and present knowing that nothing is ever finished. The next set of eyes to look on the maps will be like a new leaf after years of dormancy. It is comforting and disconcerting too. What type of work I did could determine the productivity or ability of the researcher in the future.

I feel like a voyager in ways, sailing over these maps. Their wide expanse continually unfolding under me, landscapes appearing and waning, all interpretable before they vanish. Now that I’ve reached my destination, now that the journey is over, could go back?

I took what I measured. I took what I understood and attempt ways of representing what was there. The options were infinite, but good work has finitude. In the end, “fine” appears at the end, right before the credits roll. Fine indeed.