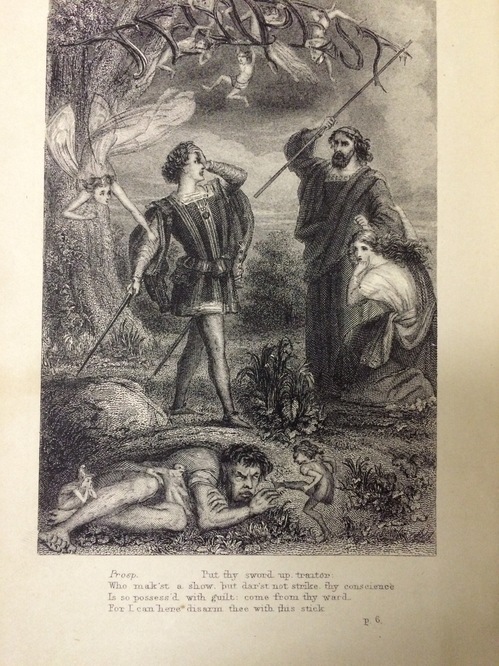

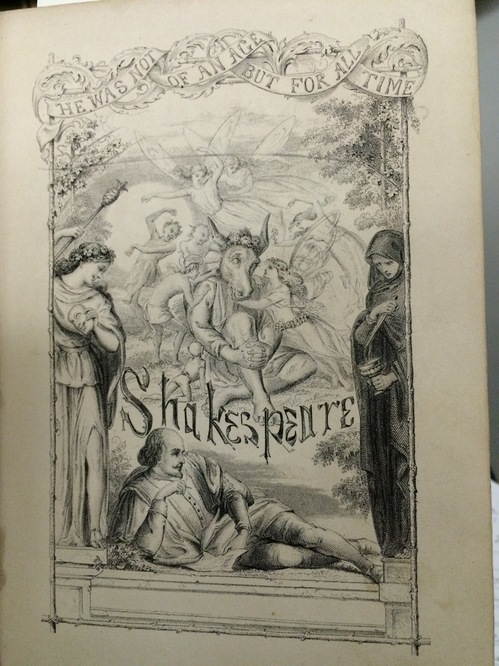

Early this week I happened upon Special Collections’ Windsor Shakespeare collection, a series of four books with 2-3 plays each inside. This collection is exciting, different from the countless others (people just loooove collecting Shakespeare’s plays), for the performance-based scribblings all up and down the margins of the book, written by Baliol Holloway (1883-1967), a fairly popular Shakespearean actor. In 1921, he performed the role of Bottom/Director in 1921 in A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Stratford-upon-Avon.

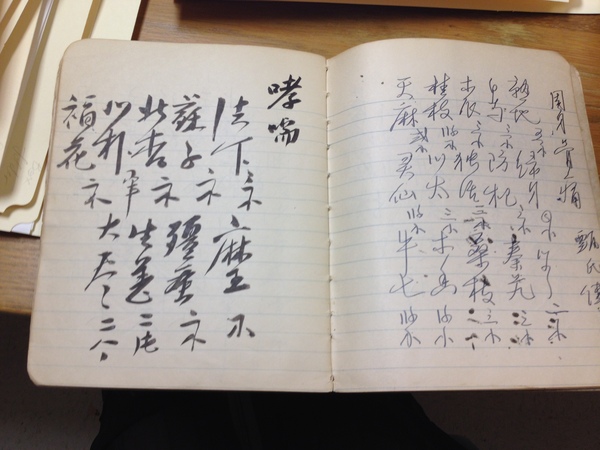

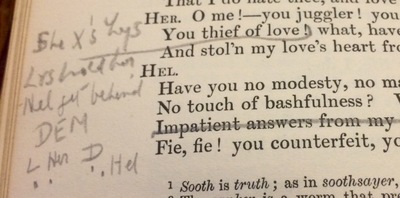

His handwriting is not incredible, unlike some of the beautiful calligraphy I’ve seen in other promptbooks and various letters. Unfortunately, a lot of the likely fascinating production notes in this copy remain a mystery to me. However one note, about the scene in which Hermia finds out that Lysander has deserted her, and confronts Helena, is quite legible, and provides some interesting possibilities for interpretation of the play and the production.

Luckily for many directors, Shakespeare’s in-text stage directions are minimal, which adds a lot of variability to the way actors and directors can take a scene. There are many emotions likely running through at least the non-addled characters in this scene, and the movements directors choose to emphasize create a different feeling for the scene.

The line that this stage direction goes to belongs to Hermia, the woman whose lover has just inexplicably changed affections: “O me!-you juggler! you canker-blossom! / You thief of love! what, have you come by night / And stol’n my love’s heart from him?” (III.ii) Unfortunately, I can’t know what the production was really like, but even based on these minimal notes it is possible to conjecture some ways the scene played out. The notes seem to say that, after the line “thief of love,” Hermia kisses Lysander, Lysander holds her (probably holds her back from running at Helena, but it could mean anything), and Helena hides behind Demetrius.

This line is directed at Helena, but the manner of its delivery is up in the air. Is she talking directly to Helena, full eye contact, taking the time to turn and kiss her lover and then yelling once again? Early in the play, Helena is bitter about Hermia’s happiness with her lover; could Hermia be trying futilely to inspire that old bitterness again, by speaking of love and then kissing her man? The kiss could be angry, spiteful, despairing, or pleading. She could be caught up in her memories of love, originally wanting simply to yell at Helena and then seeing her lover and needing to kiss him one more time. Her fire and rage can be interrupted, losing potency, or she could be channeling her feelings towards everyone into the kiss. This one stage direction adds a world of subtle but useful interpretive tools, on top of the inexhaustible possibilities of Shakespeare’s words.

There is no information about how Lysander (or Hermia!) react to the kiss, nor how entirely Lysander and Demetrius are slaves to the spell, which can be shown through body language and subtle cues. That sort of decision can only be made in the play, for those watching and those acting, but I believe that unpredictability and potential for interpretation both as actor and audience are essential parts of Shakespeare performance and scholarly study. The possibilities are endless.