Hello again everyone!

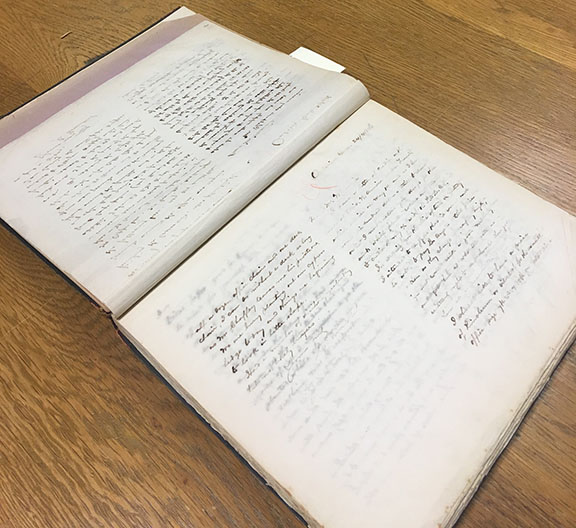

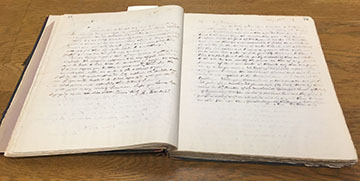

The Wet Letter Book

Before the photocopier, companies and businesses had to handwrite copies for their records. By the end of the 19th century, businesses

were using a “copy book” or “wet letter book” which consisted of sometimes a

1000 pages of razor thin tissue paper bound in a hard cover.

How the copy book worked is that the letter to be copied would

be placed under the right-hand page, while the left-hand page would be dampened

with water in order to make the copy. The

book was then closed and squeezed in a copy or letter press. When the book was

opened, the letter would be taken out to dry and its copy would remain on the

right-hand side of the book. When the Ontario Land & Improvement Co. was

conducting business in the 1880s, the use of such copy books would have been

standard practice in their offices.

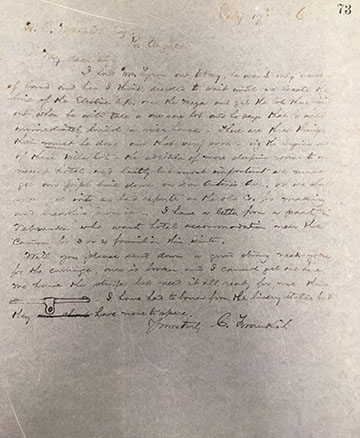

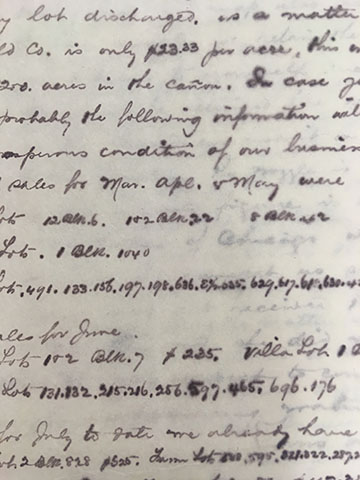

This week, I’ve been scanning the pages of a copy book

consisting of letters written by the Manager of the Ontario Land &

Improvement Co., Charles Frankish. The dates in the copy book range from April

4, 1886 to June 11, 1888, ranging in legibility due to age and perhaps even the quality of the print made by the

individual making the copies. The ink in some letters is prominent and clear, while

in others it is faded due to natural age or blurred during the copying process.

It’s interesting to think about how the technology used to

make the copies in the copy book were made with technology that was just as

innovative as the book scanner I’m using to make digital copies of that 19th

century wet letter copy book. How will

we be making copies of our digital copies 150 years from now?

Below are photographs of individual letters from the

Frankish wet letter book.

Ontario: Then and Now

Anyone who has read my past blog posts knows that one of my

biggest priorities with this project is making information accessible to

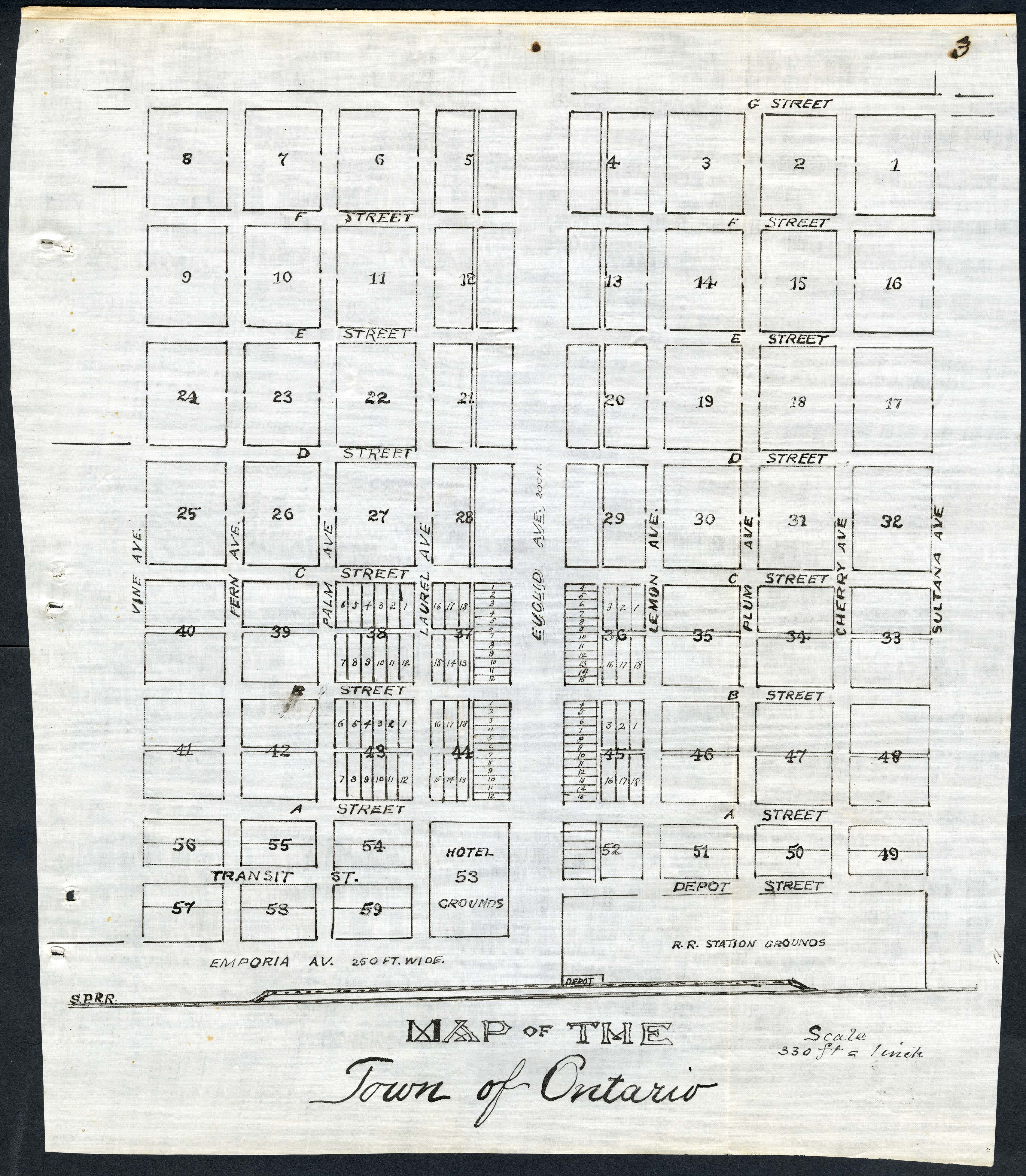

researchers. This week I came across a map of Ontario from the late nineteenth

century that intrigued me because I could imagine researchers using this map

to look at the development of Ontario, CA.

This map was made in 1883 and was found in a series of documents

pertaining to land and title companies in San Bernardino County during the late

nineteenth century.

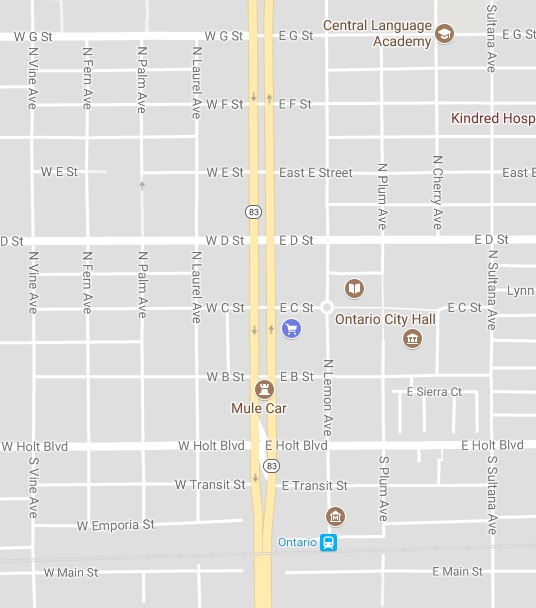

Although Ontario has changed a lot in the last 134 years,

some of the streets labeled on the map still exist today. I couldn’t resist

looking up this area of Ontario on Google Maps to see how things have changed.

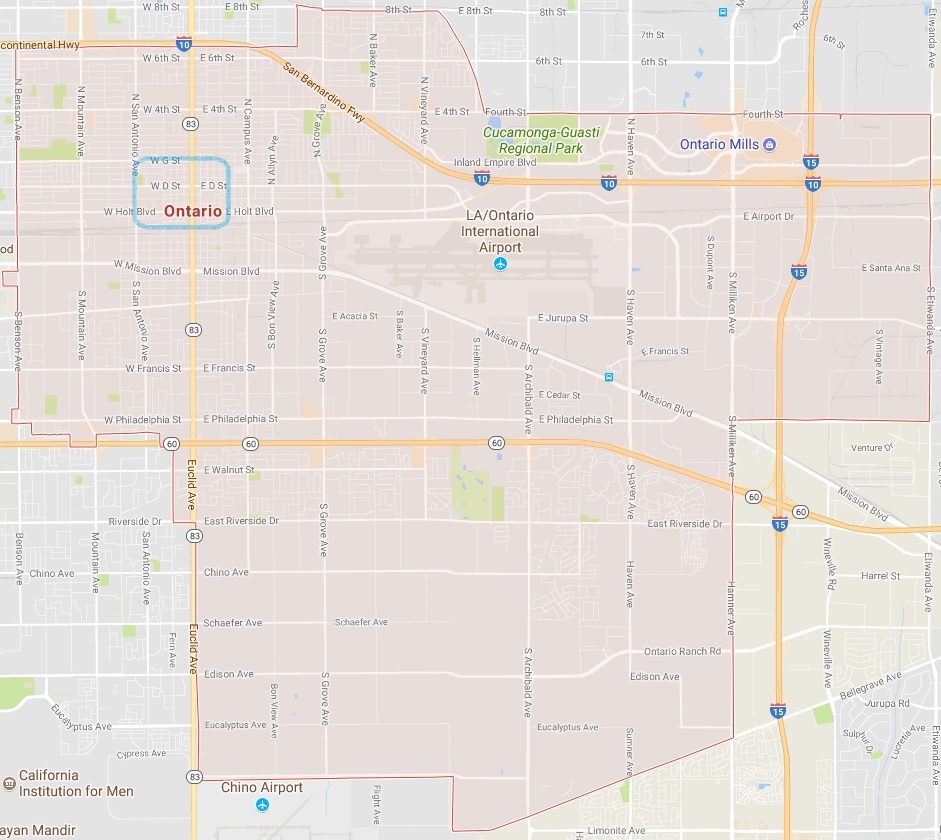

What is depicted on the map from 1883 is only a portion of

the Ontario of today. This is an image of the entirety of Ontario, CA, with a

blue box indicating the scope of the nineteenth century map.

Maps are some of the most interesting features I have come across during my time here, especially when I compare them to maps of today. Maps represent tangible evidence of how a place has changed throughout history and it gives a visually striking impression on how times have changed.

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

X-NONE

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin-top:0in;

mso-para-margin-right:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:10.0pt;

mso-para-margin-left:0in;

line-height:115%;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:11.0pt;

font-family:”Calibri”,”sans-serif”;

mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}