One important aspect of archival work is

making information from primary sources accessible to people. For the

most part this priority manifests through the creation of finding aids,

the opening of reading rooms, and the establishment of

digital libraries. The Honnold Mudd Library implements all these

features in order to invite scholars to use the Special Collections.

However, there is another way to make primary sources accessible to

potential users: through the use of social media.

Social media makes archival and special collections

accessible not only practically but also intellectually. In a practical

sense, social media accounts can help promote repositories and

encourage use by scholars and other individuals through

the more traditional means listed above. However, it also allows social

media users to engage with primary sources intellectually. The social

media presence of a repository can be a direct way of disseminating

easily digestible pieces of information taken

from primary sources. By offering this engagement with primary sources,

social media makes these sources more accessible to an increasingly

wide audience.

Social media is a great way to share fun facts,

short stories, images, and developments–this is how many individuals use

accounts like Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. Special collections

libraries and archival repositories can use social

media in similar ways. In the case of the Honnold Mudd Library and

Special Collections we use our social media accounts to share images and

videos of the collection, interesting information found in certain

documents, and new development for projects like

the CLIR Water Project. In this way, social media users engage with the

collection much as how they would use a finding aid, visit a reading

room, or browse a digital library.

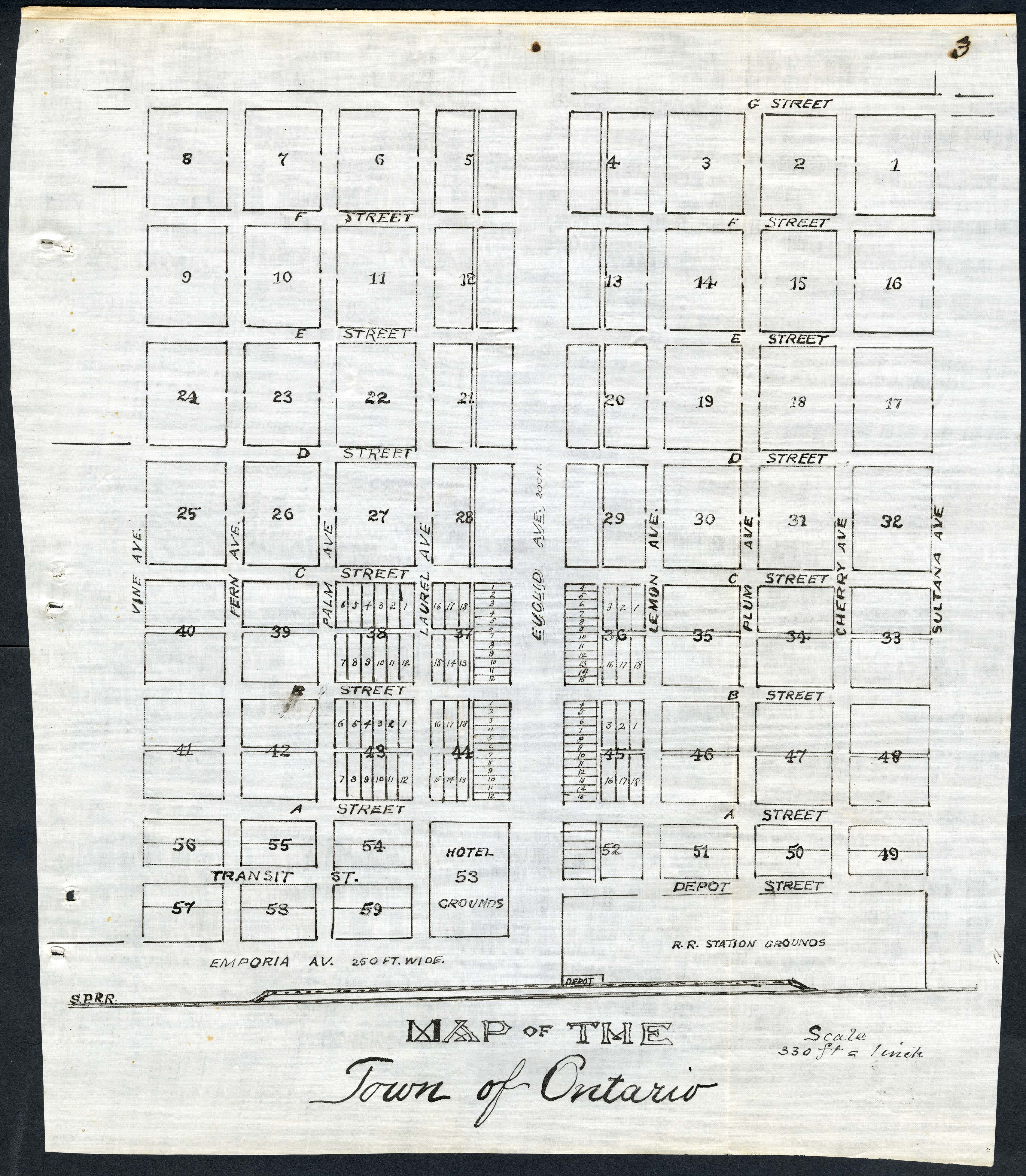

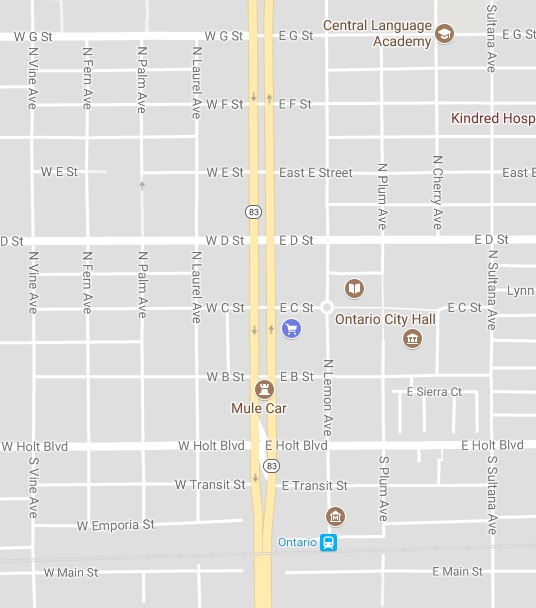

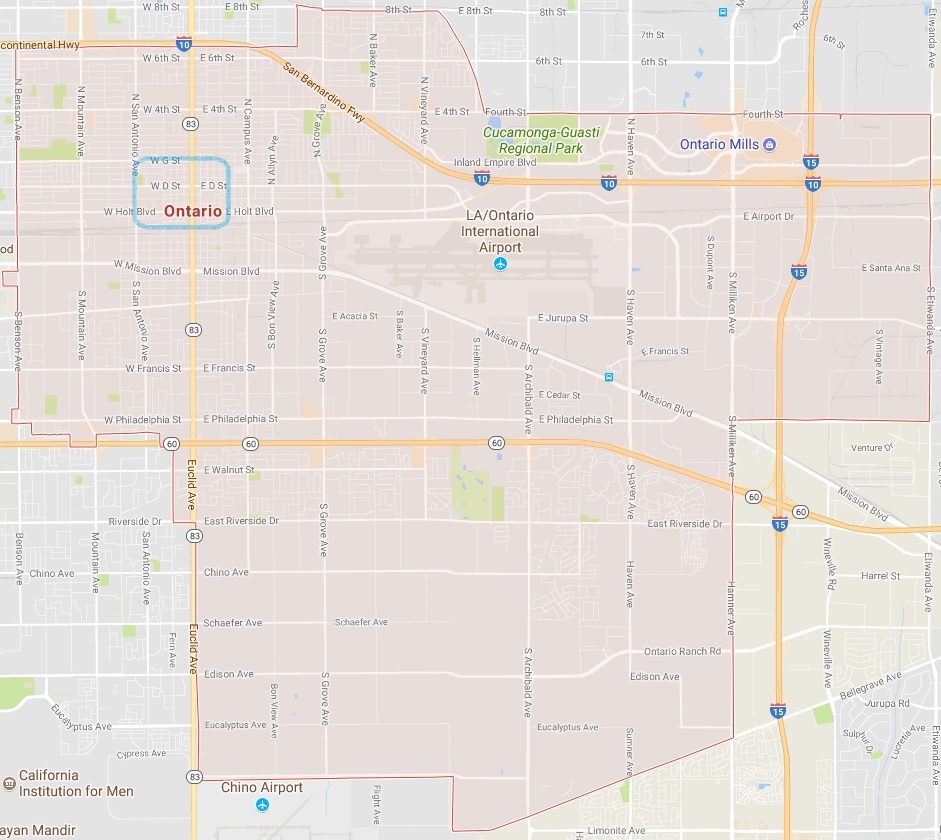

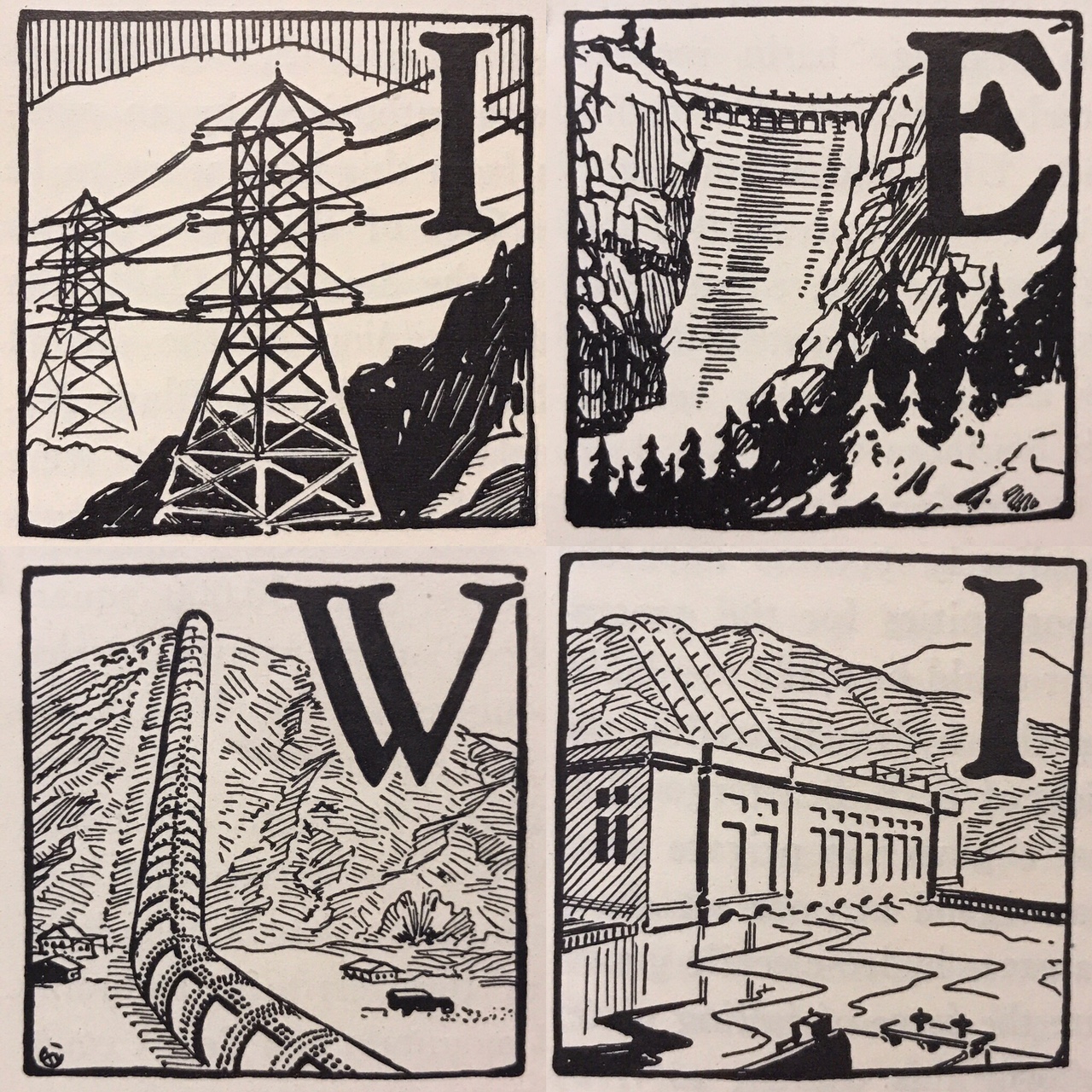

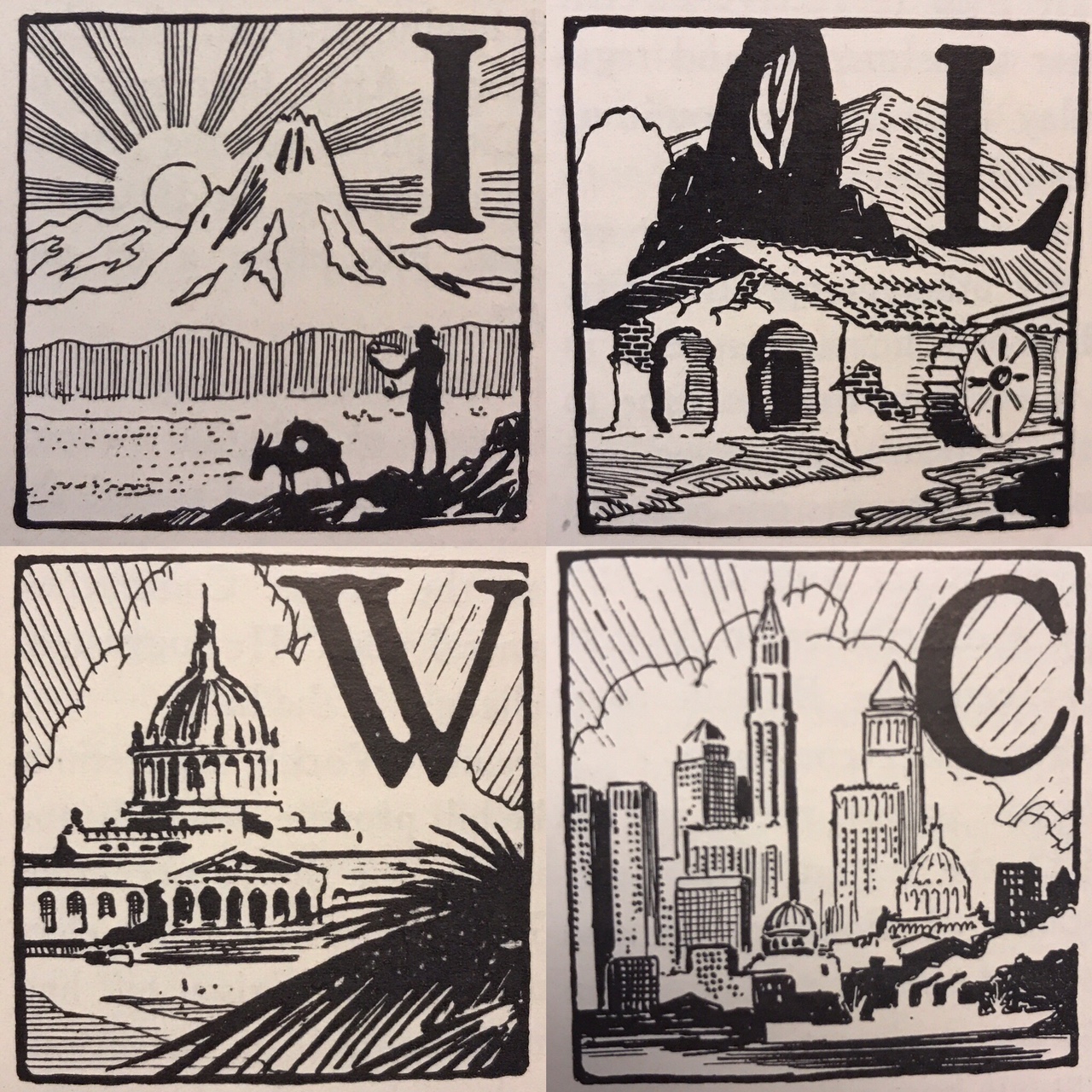

There are two social media projects I have been

developing since becoming a CLIR CCEPS fellow: #TypographyTuesday and

#WaterWednesday. These hashtags are used by our Twitter, Instagram, and

Facebook accounts. #TypographyTuesday and #WaterWednesday

usually include an image from the collection paired with a little

background information. I like to take advantage of the visual elements

of the documents I come across in the Caldifornia Water Documents

collection when I post to social media so that my posts

are eye-catching. If this blog post caught your eye and you would like

to follow #TypographyTuesday and #WaterWednesday here are links to our

social media accounts.

Twitter:

https://twitter.com/honnoldlibrary

Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/CLIRWater

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/honnoldlibrary